I was recently interviewed by ICRT about my work here at Lao Ren Cha and my views on, ideas for, and personal plans for my future in Taiwan. We talk about education, immigration, women’s movements, feminism, labor laws, international media coversge, being a Taiwan ally and more.

Have a listen here!

Monday, June 11, 2018

Wednesday, June 6, 2018

Firewalking For Beginners: my latest for Taiwan Scene

I'm back as a guest contributor to Taiwan Scene, this time writing about firewalking in Donggang...but not the way you think. It's actually about being a female traveler faced with sexist (yes, sexist) religious traditions, and having entirely the wrong response to them - something I can only admit now.

In any case, enjoy.

In any case, enjoy.

Tuesday, June 5, 2018

It's like air: Tiananmen in Taipei, 2018

Honestly, I feel the need to write about the Tiananmen Square memorial event held yesterday, June 4th not because I think I have anything unique to say about it that others couldn't, but because this year it felt so lightweight that if we don't note it down for the collective Internet memory, the event as a whole will just float away, as though it never happened. Which is, of course, exactly what the Communist Part of China wants. Nobody likes the world remembering massacres they perpetrated.

The event was mostly in Chinese, with a few speakers addressing the crowd in English. I would like to suggest here that the entire event should be bilingual, and next year's 30th anniversary event might actually make the news, so it would be smart to have translators ensuring all talks are available in English and Chinese. I can follow the Chinese, but I can imagine many foreigners in Taipei who'd be otherwise interested in attending might not, because it's not very exciting to hear speeches in a language you don't understand.

As usual, the event featured a number of speakers from a variety of activist groups across Asia, including recorded talks from Uighur activists, two speakers from Reporters Without Borders (based in Taipei) and a particularly electrifying speech by Vietnamese activist and Taipei resident Trinh Huu Long. Yu Mei-nu, Yibee Huang and Zheng Xiu-juan (Lee Ming-che's boss, although that sounds odd to say in English) were some of the Taiwanese speakers.

Zheng likened China's human rights abuses to its intractable pollution problem, saying that "human rights are like air" - when you're breathing comfortably you don't notice them, but when the pollution ratchets up to PM 2.5, you realize how vital clean air to breathe is, and suddenly you're suffocating. (I'm translating roughly from memory here).

|

| Zheng Xiu-juan (鄭秀娟) and Yibee Huang (黃怡碧) |

There were also performances, including a memorable entrance by Taiwanese rapper Chang Jui-chuan (張睿銓), who sang one of his newer songs, Gin-a. The lyrics (in Taiwanese) discuss Taiwanese democracy movements and freedom fighters post-1949:

Killing after killing, jail after jail...

Hey kid, you must remember

Their blood and sweat, torment and sacrifice

Gave you the air you're breathing

|

| Empty chairs at empty tables |

And that's just it - the 6/4 event, held every year, feels like a part of the air here in Taiwan. It just happens, everyone knows it happens, and they assume others will attend so they take it for granted. It's there, it's always there, maybe next year, someone will show up. I don't need to worry about it. Ugh, Monday night.

What you get, then, is an attendance rate that looks like it might have been less than 100 (but damn it, Ketagalan Media made the effort. We showed up.) Which, again, is exactly what the CCP wants - for us to forget.

In 2014 this event was huge, with camera lights stretching back into the distance and prominent Taiwanese activists showed up - including Sunflowers fresh off the high of electrifying society and about to watch the tsunami they started wash across the 2014 elections. We thought we could change Asia. We thought it was within our grasp...and now there are empty chairs stretching back, and nobody seems to notice the air they're breathing.

Some say it doesn't matter, or is odd to hold in Taiwan, as China is a different country. It's true that China and Taiwan are two different nations. What happens in China affects Taiwan, though, and hosting memorial events so close to China and in venues where a number of Chinese are likely to walk by does make a difference, if a small one. We're on the front lines in the fight against China's encroaching territorial and authoritarian expansionism, so it means something to take a stand - even a small one - here.

In 2016 an entire group of Chinese tourists walked right past the event - this year, someone seems to have ensured that wouldn't happen again. For once, Dead Dictator Memorial Hall was completely devoid of Chinese tour groups and I doubt that was a coincidence. What I'm saying is, somebody noticed.

It also serves as a reminder that Taiwan is not China - we can and do hold these events here, and we do so freely and without fear. We talk about our history, as Chang does in Gin-A. We discuss our common cause, as democracy activists from across Asia did last night. What we do - let's not forget human rights abuses that happen in Taiwan - may not perfectly align with what we stand for, but we talk about it, and we have the space and air we need to work toward something better. In China you can't breathe at all.

But the people who died at Tiananmen 29 years ago are among those whose sacrifice may eventually give China the air it needs to breathe - though I grow less sure that it might happen in my lifetime. Fighters like Lee Ming-che, thrust into the national spotlight and just as quickly forgotten even in Taiwan, give Taiwan the air it needs to breathe. We give ourselves air and beat back the oppressive particulates trying to suffocate us, by standing up for what's right and refusing to forget the massacres of the past.

We must remember. We can't let this event float away on the air, as though it doesn't matter, or it doesn't matter for Taiwan. It absolutely does.

I mean, I get it - I'd like to feel totally safe knowing my freedom and guaranteed access to human rights was not in question. I'd like to sit on the couch and eat Doritos and not even worry about it, because I don't have to. It's tiring to keep showing up. Unfortunately, Taiwan really is on the front line, and we can't do that - we can't pretend it doesn't (or shouldn't) matter.

Next year is the 30th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square Massacre. Mark your calendar now, make sure you're free, and show up.

Saturday, June 2, 2018

Another kind of missionary

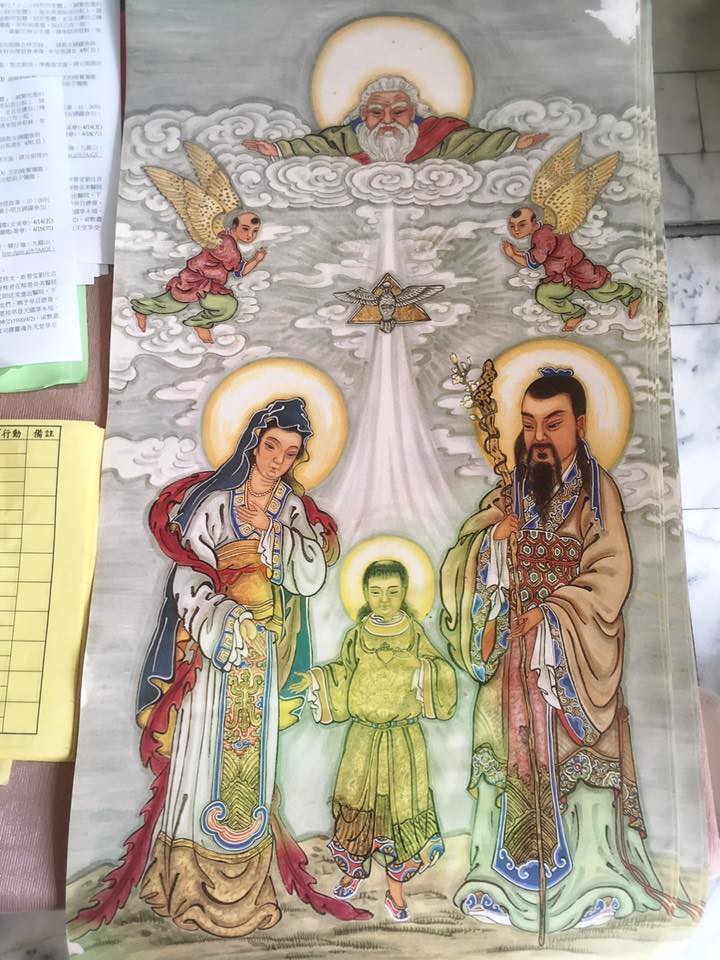

|

| A very "Chinese" Last Supper at the Catholic church in Yanshui, Tainan |

Something that's been kind of in the back of my head for awhile, brought to the fore by my friend Donovan's interview with a missionary, and then the editorial some guy wrote about it. Now I'm writing about the editorial. Perhaps someone will write a piece about my blog post, and someone will tweet about that, and someone will write an editorial about that incendiary tweet, and then someone will Snapchat it or Tinder it or Grindr it or Blendr it or whatever the kids are doing these days, right up until Donovan covers the whole thing on ICRT again. The circle of life.

Anyway, friends and regular readers will know that I don't care for missionary work. I understand that many missionaries do other good things for communities, but I can't condone the 'I claim to respect your culture but I actually think this part of my culture is better and you should trash what you did before' attitude, or the idea that one does good works toward the ultimate goal of converting people. I say this even as I acknowledge that I can like and even respect individual people of good character who are missionaries.

In any case, what struck me about Mr. Angrypants here wasn't his views on missionary work which I largely agree with, but this:

Academic institutions must focus on the enhancement of logical, critical and independent thinking. Unfortunately, core values of the local culture here are not amenable, often even inimical to such essential educational goals.

The prevailing culture here is authoritarian and honors blind obedience, its education awards rote learning without understanding, it discourages young people from thinking for themselves and it punishes inquisitive minds.

The disingenuous educational paradigms are implemented in so many classrooms here on a daily basis. Therefore, there is no need in Taiwan of an additional input of uncritical thinking by religious groups that aim to hijack the minds of young people through the indoctrination of dubious contents.

I don't entirely disagree with this, though I don't necessarily think my education was that much better. But, it can't be denied that this is a large component of the educational system in Taiwan. Every time I start thinking "oh it's not that bad", I recall a story an adult student (and legit genius and overall cool person) once told me. As a student, he'd had to write three essays, each on one of Sun Yat-sen's Three

I don't even blame Taiwan for it too much: it's a holdover from authoritarian rule (dictators want populations that can read, write and do math, but not think too much) that sticks because it claims on the surface to have cultural legitimacy (I'll come back to this). Changing it would take a complex organized effort that considered parents, professional curriculum development, exams, administration and long-term teacher development. I understand why it's so slow to happen.

In short, he's got his tenses wrong. The prevailing culture in Taiwan was authoritarian, but is now democratic with a strong penchant for social movements and activism. The education system just hasn't gotten with the program.

I also suspect quite a few Westerners fundamentally misunderstand the historic role of education in many Asian cultures. Yes, it involves a great deal of memorization, especially of the "classics" (or math equations, or grammar patterns, or whatever). If you do this, you will pass. But historically there has also been a belief that to be truly 'educated' - to be a scholar - it's not enough to simply memorize. You have to take what you've learned and glean insights from it that you can apply to real-world situations. You have to be able to use it, extrapolate on it, consider it, do something with it. Otherwise, you might pass, but you're not a scholar.

Or as we call it in the West, critical thinking.

I'm not an advocate of this particular method of leading learners to criticality and inquisitiveness - it's outdated and just doesn't seem to work that well - but it's simply not true to say that educational traditions in Asia sought to suppress such traits.

But that's not where the real problem lies. This is:

There is another reason for concern. It is obvious that so many young people in Taiwan are literally clueless about major issues that move the world. Their life experience is minimal, their minds are soft and malleable, underdeveloped, easy to bend....

Often, young people are emotionally and intellectually insecure; they have never developed their own ideas about topics of general concern. They are lost when having to move within competitive networks of opinions, assertions and claims — the stuff the modern world is made of.

Therefore, they can be easily manipulated and “guided” by those who do have opinions, no matter whether they are good or bad.

|

| Asian Mary, Jesus and Joseph (Frankly I'll take this over |

I'm guessing he doesn't spend a lot of time around Taiwanese student activists. If you think they are easily manipulated or their opinions can be changed or bent, just ask Ma Ying-jiu how that worked out for him.

Seriously, this is one of the most offensive things I've ever read about Taiwan.

Mr. Dude turns a somewhat-valid criticism of the educational system in Taiwan into a narrative of ‘these poor dumb mindless Taiwanese are at the mercy of these missionaries’ as though they are hapless victims too stupid and thoughtless to run their own society.

You know, that society that I just noted above has a strong tradition of activism (nevermind that it used to be called 'rebellion')? The one with arguably the most successful democracy in Asia, some of the freest press in Asia if not the world, with a developed economy that they (not the dictatorship) built?

That society, apparently. According to him, it's full of morons who don't even know how to have opinions.

This literally makes me want to spit. While I don't pretend Taiwan is perfect - there are many issues here that deserve strong, if not vicious, criticism - in this particular way, I have to wonder if we're living in the same country. I mean, sure, I meet idiots here. Every country in the world has its thinkers, its average people and its, um, dimmer bulbs. Every country has its leaders, its normal people and its blind followers. But to just not see all the creativity and insight around him? What's up with that?

For every thicker-skulled person I meet, I also meet people like my student above, who risked a failing grade just to write what he really thought. I see students occupying...all sorts of things, or trying to. I see the student I had who envisioned his presentation as a series of interconnected three-dimensional cubes, in a really insightful way that I hadn't even considered as a potential mind map. I see all the great Taiwanese fiction I've read recently, the beautiful films, the students I tutored who came up with a way to safely and more easily carry water over long distances while using the movement of that water to charge a battery that could be used for electricity, the creatively-decorated cafes, the young people with ideas that they'll launch once they get the money.

I see that while the authoritarian-holdover educational system in Taiwan is accepted, it is not particularly well-liked. Most Taiwanese are well aware of the flaws, and it's entirely understandable that fixing them seems like an impossible effort (if you want to criticize this, fine, but go look at American public schools in underprivileged areas and come back and tell me you still think Western countries are 'better').

I see a country where the education system doesn't teach critical thinking, but plenty of people learned to think critically anyway.

So this guy thinks he has all the answers for how to make Taiwan better and if we’d just do what he says those poor, poor, POOR widdle Taiwanese wouldn’t be taken in by those evil big bad missionaries. Just listen to him, he’ll fix what’s wrong with Taiwan.

He knows how to make this foreign culture better, more thoughtful in ways he can relate to, more like his vision of what it should be like. Of course, without his brilliant insight Taiwan will be lost. Barbaric. Stuck in the past. Or something.

In other words, he's just another kind of missionary.

Wednesday, May 30, 2018

Book Review: Lord of Formosa

It is a pleasure for a work of historical fiction to come out on an area of history I am particularly interested in (Taiwan, obviously). It is an even greater pleasure when that work of historical fiction is not only engaging, but generally accurate. Joyce Bergvelt's Lord of Formosa has earned both of these adjectives.

Lord of Formosa is essentially a biography of Koxinga (國姓爺 or 鄭成功), the 17th-century scholar/pirate/businessman/military leader/talented crazy dude, from his early life on the Japanese island of Hirado (off Nagasaki) with his Japanese mother, Tagawa Matsu to his upbringing at his father Zheng Zhilong's (鄭芝龍) estate in Fujian, followed by his rise as one of the most talented loyalist military leaders resisting the encroaching Manchu (Qing) conquerers to his conquest of the Dutch colony on Taiwan. It's interspersed with viewpoint chapters from the Dutch colonial officers as well as Koxinga's parents.

It tells the story, in short, of a man given the Imperial Surname (國姓爺) by a dying empire, a man given the title 'Success' (成功) who was, in the end, not all that successful.

The story itself is somewhat tragic: Koxinga fulfills what the novel depicts as his 'destiny' but pays for it dearly. He has to choose between remaining loyal to the collapsing Ming dynasty or to his father, and watches the devastation of his family at the hands of the Qing.

"He literally died of a broken heart," an acquaintance of mine noted.

But no, to hear historians tell it, he probably died of syphilis.

In this way, the thick novel is cinematic in scope, at times reading like a biopic. It would make an excellent film, and I can only hope someone will pick up the rights and do just that (as long as it's not a Chinese company hoping to use it as a propaganda vehicle for their government's aggressive territorial expansionism).

From the beginning, I was interested in how accurate Lord of Formosa really was. So, just after reading it, I picked up Tonio Andrade's Lost Colony, figuring it would be a good nonfiction counterpoint. I'm partway through that book now, and am surprised more by how much is accurate than the small details which are spun with more artistic license.

However, this isn't even the highlight of the book: the best part is simply how much fun it is to read. Despite being extremely busy, I read Lord of Formosa in three days, staying up late one evening to finish it. You know a book is good when it's 3am and you know you aren't going to get enough rest that night, but you just keep going because sleep won't happen anyway.

I also appreciated how forthright Bergvelt is with her characters' flaws. Zheng Zhilong is, to be frank, a total douchehole both in terms of his defection to the Qing and his treatment of his first wife. If his son Koxinga was any kind of hero, he was a deeply flawed one: often cruel and despotic, suffering from fits of uncontrollable rage which might have been brought about by the aforementioned syphilis. Of course, the syphilis would have been brought about by all the mostly-nonconsensual sex he was having.

What I'm trying to say is that Koxinga might have been brilliant, but he was also super rapey.

His regretting it later (in the novel's telling) doesn't change that. Oh, and like father, like son.

In fact, that Bergvelt successfully created a story that includes a variety of relevant, realistic female voices - not all of them kind, pure-hearted heroic martyrs - in a story and era that is so deeply, unrepentantly penis-driven (my masts are bigger than your masts - let us do naval warfare!) is a literary feat. While she could have done more with the housekeeper, Lady Yan and Koxinga's wife Cuiying, she does enough to show that behind every story of dueling dicks, there are women who also drive the plot. And yet, she doesn't shy away from exactly how those women are treated.

The Dutch, who are portrayed not entirely unsympathetically, still come across as stupid - not really understanding Asia or the goings-on in the colonies they ruled - as well as greedy and racist. This was historically accurate: they did consider Chinese men to be 'effeminate', not a fighting force that could vanquish their (smaller) military might. That's racist. They didn't care nearly as much about the welfare of the people on Formosa, be they indigenous or Hoklo, as they did their profits. This is not only historically accurate, but also racist.

On the other hand, Koxinga was kind of racist too - believing he had the right to take Taiwan because most residents by that time were Chinese (mostly brought over as laborers by the Dutch, who worked them like serfs) and therefore Taiwan ought to be a part of China, is just a different way to be racist. He didn't 'liberate' Taiwan from colonizers - he was just another kind of colonizer.

If I have any criticism of Lord of Formosa, it's that that point could have been made more forcefully.

Bergvelt takes a few artistic liberties. There was a fortune-teller in Japan who was more of a plot device than real character. I'm not sure how many of the Hoklo characters on Formosa were real people (though at least two - Guo Huai-yi and He [Ting]-bin certainly are). It is not clear how Tagawa Matsu died, although Bergvelt's telling of it is plausible, or even likely. Koxinga is depicted as growing less rapey over time (but still, again, super rapey) due to the effect his mother's death has on him. I'm not sure this would have played out in quite that way in real life - more likely, he was incapable of comprehending that the sex he unilaterally decided to have with women who didn't resist per se but also didn't consent is just as rapey as what Qing soldiers were doing. In other words, he didn't stop being rapey - he was just another kind of rapist.

That said, Bergvelt is a talented writer, understanding seemingly innately where to hew to historical accuracy and where to apply a bit of soft focus or streamlining. The story moves forward when it needs to (although I would have liked to have seen more of Koxinga's childhood in China) and lingers where it needs to.

Whether you are into historical fiction, want an engaging read of a period of Taiwanese history in particular, or just like a good novel, I strongly recommend it.

Monday, May 28, 2018

Book review: Women's Movements in Twentieth-Century Taiwan

When talking about Taiwanese history, it's quite common to come across a belief that modern Taiwanese beliefs have their roots in the 1970s, and did not really exist before that. From "there was no real sense of Taiwanese identity or a Taiwanese identity movement before the 1970s/the Kaohsiung Incident" to "there is no history of feminism in Taiwan before the 1970s/before the end of the Chiang Kai-shek era" and more, it surprises me how many people truly think this is the case.

Of course, when it comes to Taiwanese identity, this is manifestly false. There are records of autonomous rule movements as early as the late 1800s, and several sources reference similar autonomous movements in the Japanese colonial era. When it comes to women's movements, the same applies. While several feminist pioneers did bring ideas of gender equality to the mainstream in the 1970s, the first stirrings of modern autonomous (that is, not connected to, supported or funded by the government) women's movements in Taiwan have their roots in the Japanese era, although there's no evidence to suggest that the 1970s feminists were directly influenced by them.

It seems to me that misrepresenting both of these movements as originating in the 1970s rather than several decades earlier is an intellectual sleight-of-hand meant to create the idea that both are new, "Western" notions that have no natural roots in Taiwanese culture or history (therefore creating a platform from which to criticize modern Taiwanese identity and feminism). In both cases, such notions are disingenuous.

This is just one of the many things I learned from Women's Movements in Twentieth-Century Taiwan, a slim volume (for an academic book) by Doris Chang. And, for an academic title, it reads surprisingly smoothly.

As an individualist feminist, I appreciated being challenged on the different notions of what feminism could be. I am not a relational feminist - I don't believe my equal place in society comes from the fulfilling of my different but complementary duties vis-a-vis a family or collective society - but as Chang makes clear, this is indeed a form of feminism, and one of two strands that continues to exist in Taiwan (and, arguably, the one that can strike the best compromise with traditional notions of role, duty and family in Taiwan). Chang further clarifies, however, that this is not the only strand of feminist thought present in Taiwan, as many would believe: radical feminism, woman-identified, X-centric and individual feminism also exist.

If I took one thing from this book, it's a reminder that Taiwanese society is not so simply categorized as traditional/collective/Confucian/whatever adjective you want to describe your idea about ~*~The Mystic East~*~. It's far more complex than that, and there is a place in public discourse for ideas that don't fit neatly into this narrative.

Chang makes other important points as well: for example, until fairly recently, the story of women's movements in Taiwan was once controlled by a China-centered narrative which began not in Taiwan, but with the founding of the Republic of China in, well, China. Taiwan only enters this narrative after 1945 (you can guess why), with women's history under Japanese rule being erased: non-existent, foreign or irrelevant to the story that the Sinicizers want to push.

Hmm, that sounds similar to Taiwanese national history as a whole, doesn't it? Not so different from teaching schoolchildren that their country was founded in 1911 (nevermind that that happened in China, and nothing important happened in Taiwan on that day) and then erasing Japanese era history in Taiwan to cover the Republic of China's Greatest Hits, Vol. 1 instead, no?

Chang also provides short histories of notable women in the early and mid-twentieth century, and devotes entire chapters to scions of the movement such as Annette Lu and Lee Yuan-chen, showing that the only reason we believe history to be full of notable male characters but few notable women is because we've constructed it that way, not because it always happened that way.

She also discusses the ways in which autonomous women's movements differed from government-affiliated ones. You won't be surprised to learn that the Japanese and ROC-affiliated women's movements promoted not feminism, but the fulfillment of traditional gender roles (shocking, I know.) She covers Soong Mei-ling's use of women's organizations mid-century to work toward national goals with very little concern for the actual issues facing middle-class and poor Taiwanese women.

I was interested to learn about the origin of those "Model Mother Awards" as well (you won't be shocked to learn they began in the worst years of the ROC dictatorship, because doling them out supported national goals), and her touching on the ways in which women's labor helped catalyze the Taiwan Miracle, although I think she could have made that point more forcefully than she did.

And, of course, she covers the ins and outs of elitism in women's movements, the relationship of women's movements to democracy/pro-Taiwan movements, Awakening and the Taipei Women's Rescue Foundation, the cooperation and rift between liberal feminists and lesbians, domestic abuse hotlines and more, finishing up with the ways in which the pioneers of the 1970s were able to really flourish (as well as separate into different groups) with the lifting of Martial Law, and the bevy of women's rights laws that were passed between the mid-1980s and the end of the 20th century.

I have one abiding criticism of Women's Movements in Twentieth-Century Taiwan, which is that it follows a bluer narrative than you would expect. That is not to say it doesn't criticize the KMT, the Republic of China or its leaders (it absolutely does, often viciously and entirely rightly), but that it includes certain problematic historical constructions that if anything are surprising. Here is just a taste (underlined emphasis points are mine):

In 1987, the Kuomintang lifted martial law and ushered in Taiwan's democratization.

(No, the Kuomintang was forced by the Taiwanese to do that.)

The Dutch colonized the island....the government of the Qing dynasty incorporated Taiwan into the Chinese Empire.

(You already know how I feel about this.)

With the defeat of Japan in World War II, the Allies transferred the governance of Taiwan to the Kuomintang government.

(Nope. And the KMT knew this - scroll down).

The Taiwanese duality of both sameness and with difference from mainland China has contributed to the Taiwanese people's unresolved national identity since the 1940s.

(While identity has absolutely been a core question in Taiwan, the origin of ambiguity in Taiwan's national identity comes from colonial regimes from China - first the Qing, now the ROC - who insist on promoting a Chinese-centered national identity. If they had not pushed that point from their foreign perspectives so forcefully, Taiwanese national identity would not be in question. In fact, these days the question is mostly resolved, but the book was published in 2009 so I can forgive this.)

There are a few more examples, including many jarring uses of that horrible word "mainland", implying a territorial connection that simply isn't there - the current PRC government of China has never ruled Taiwan - but you get the point.

In any case, it was a worthwhile book if you can look beyond the odd blueness of the language used - as engaging as an academic text can be (though a bit heavy on the 'thesis statements' as though someone is grading it), full of lots of knowledge drops. Despite one or two confusing narrations of timeline (I'm still not sure when and why the New Life movement moved away from May Fourth Movement ideals and toward more traditional precepts, and the section on that did not clarify), I learned a lot and am happy I read it.

If you are not already knowledgeable about women's history in Taiwan, I recommend you do, too.

Sunday, May 27, 2018

I read a book and obsessed over Annette Lu

|

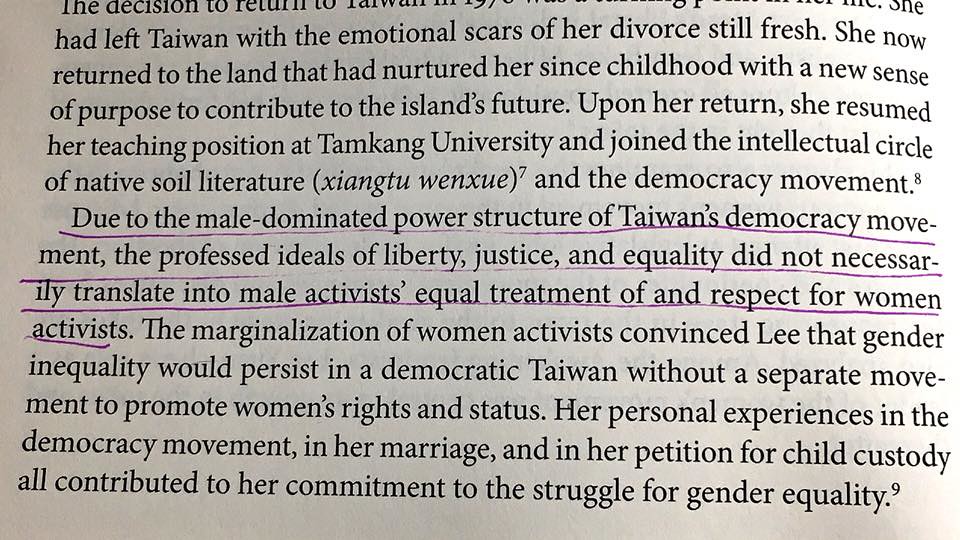

| This passage is about Lee Yuan-chen, not Annette Lu, but the point applies regarding how she's been treated. |

Add former Vice President Annette Lu (呂秀蓮) to the list of people who vex me. Reading more about her contributions to the feminist movement in Taiwan was the most impactful part of Doris Chang's Women's Movements in Twentieth-Century Taiwan for me, so I'd like to devote a post to talking about that before I drop a more complete review.

The book devotes a long chapter to Lu, who these days has a reputation for being both off-kilter and out-of-touch. It's not hard to see why.

When looking into what people dislike about Lu, I find stories that range from an odd trip to Indonesia as vice president (reported sympathetically in the Taipei Times) to comments on AIDS that many took as blaming gay men for the AIDS crisis as "God's punishment" (and frankly, I have to agree with that interpretation of her meaning) to a confusing proposal for Taiwan's diplomatic neutrality to completely unwarranted attacks on Mayor Ko and last year's Universiade. And, of course, announcing her intention to run for Taipei mayor when she is, frankly, not all that popular and doesn't seem to realize it. And, of course, there's her support of the ill-fated 'independence referendum' which takes so much energy that could be used to combat real threats to a more liberal future for Taiwan, and pours it into a big fat waste of time.

Then there is what I saw myself: She came to the 330 protest to support the 2014 Sunflower Movement (I don't have a link, I'm telling you this because I watched her walk by with my own eyes), despite the movement having little to do with her, and the general feeling that the DPP was trying to capitalize on the movement to build their own support when the Sunflowers themselves were not particularly interested in DPP party politics. Actions like this were a part of why many Taiwanese on the fence about the Sunflowers came to believe they were a DPP plot, when they were nothing of the sort.

Chang, on the other hand, focuses specifically on Lu's activities in the 1970s, and makes it quite clear that Taiwan would not be where it is today vis-a-vis women's equality if not for her. A thread of belief is drawn between her - the first and most prominent Taiwanese feminist of the second half of the twentieth century - and the women's groups of early-20th century Japanese Taiwan, but makes it clear that from a research/scholarship standpoint, there is no evidence that the movement Lu ignited (no, it is not an exaggeration to say so) was directly related to earlier women's rights activities in the country. I do not think it is too much of a stretch to say that perhaps the reason why Taiwan is ahead of the rest of Asia when it comes to women's issues is in large part thanks to her. She didn't do everything - there are many other notable Taiwanese feminists of the 80s and 90s - but she struck the match in the 1970s and that means something. She printed books, founded associations and opened hotlines during a time when one could be arrested or 'watched' for doing so: and she was.

Her feminism was not perfect: she was in favor of ending arranged marriage (still somewhat common in Taiwan even as late as the 1970s) and she herself chose not to marry. She spoke out in favor of women succeeding professionally, as she had done. However, she tried to build support through compromise: not attacking the (wrong) idea that women still had specific duties in the home that should not be done by male family members, with no ideas as to how to ease the 'double burden' this dual set of responsibilities - familial and professional - puts on women. She was not in favor of pre-marital sex (though advocating for not discriminating against those who chose to engage in it). She tried to marry feminism with the idea of Confucian duty, and frankly, it didn't work well for good reasons.

In fact, she came into feminism long before she became a dangwai or pro-independence activist, to the consternation of many of her less party-bound (or simply blue-leaning) feminist peers who felt that the fight for women's equality should not be bound to other political goals (many if not most did not join the dangwai as Lu did).

Her doing so anyway - and suffering for it, having been imprisoned and tortured with other pro-Taiwan activists for her role in the Kaohsiung Incident - could be said to be part of why feminism in Taiwan is now linked to some extent with pro-independence, human rights and other liberal activist movements. It's a logical progression: women's movements supported by the KMT, especially in the White Terror era, were not equality-minded at all but rather promoted the continuation of traditional gender roles and beliefs about gender and duty. It only makes sense that a different set of beliefs about equality would eventually be tied into an anti-KMT, pro-Taiwan platform. Yet without Lu, this might not have happened.

This national amnesia about her contributions to the women's movement means that her current beliefs are often presumed, perhaps unfairly. Some say she opposes marriage equality, but the only source I can find for that are interpretations of the aforementioned AIDS comments. Having been made 15 years ago, I'm not sure that's a strong enough case to interpret her feelings on the issue today. Soon after those comments, she drafted a basic human rights law that included marriage equality, which didn't pass.

Yet, people assume that one (extremely stupid and bigoted, to be true) comment about AIDS represents her entire worldview, which I feel is unfair, and it seems nobody has asked her what she thinks of marriage equality today.

This has led me to believe that perhaps she doesn't get enough credit, even as we acknowledge that she has not represented the zeitgeist for decades and regularly makes groanworthy statements today. It doesn't surprise me: scions of other liberal movements are regularly forgiven for their later missteps - Christopher Hitchens and Richard Dawkins come to mind - but women like Lu? Well, I wonder why they aren't. Why are her past contributions so easily forgotten? If her statement on AIDS, which rightly deserves all of the criticism thrown at it, is used to frame her entire belief system, why is the same not often done for so many male public figures?

I can't help but notice that, while other human rights advocates of her era such as Shih Ming-te are also rightly criticized for their out-of-touch and off-kilter (and often downright insane-sounding) pronouncements today, some are quick to point out that serving time in prison under the KMT dictatorship would drive anyone to be a bit, uh, nutty. Yet few seem to remember that Lu spent over five years as a political prisoner as well. Shih gets the background context for his behavior, Lu just gets eyerolls.

(That said, if I could vote, I would not vote for her for Taipei mayor. She's done a lot, but she would not be a good mayor, period.)

There is still more work to be done: Lu is brushed aside - sometimes rightly so, sometimes perhaps without due consideration of her important contributions to the women's movement - and the slow liberalization of Taiwan chugs along. The southern and older social conservatives who make up much of the DPP's pro-independence supporters are growing old, and will be replaced by younger, more progressive voters. In the here and now, though, these older conservatives still matter, yet we forget that there are people like Lu who began challenging them, however imperfectly, decades ago.

The younger, more liberal generation itself has work to do. As Chang notes in Women's Movements in Twentieth-Century Taiwan:

Due to the male-dominated power structure of Taiwan's democracy movement, the professed ideals of liberty, justice and equality did not necessarily translate into male activists' equal treatment of and respect for female activists.

This was true when the book was written, and it was true in Lu's time as well. She challenged it, and made it to the vice presidency.

The problem is, it's still true today. Look at the Sunflowers, whose large-scale protest she attended. How many prominent Sunflowers are male? How many are female? How often are male NPP legislators (Freddy Lim, Huang Kuo-chang and Hsu Yung-ming) in the public eye? How often are the female legislators (Kawlo Iyun Pacidal, Hung Tzu-yung) in the public eye?

Despite a great deal of progress having been made, do we really think that today's liberal progressive youth is that much better vis-a-vis women's equality than in Lu's generation?

Because as I see it, Lu understood this before the rest of us did. Maybe she's out-of-touch now, and it is frankly time for her to retire. She is now hindering the movements she once championed. But that doesn't mean we give her enough credit or that we can ignore the ways in which the work she started still is not done.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)