Every Saturday I tutor the younger daughter in a family I've known for many years. We get along well and I mostly facilitate extensive reading and writing, so not a lot of traditional grammar exercises (though in her own time she works through a huge grammar book and I'll check her work - her idea, not mine.) But, I noticed one day that she was struggling with use of various passive and past perfect forms, so I said I was going to check her knowledge of Taiwanese history using passive-heavy questions.

I wrote down a few questions along these lines, for her to render correctly before answering. Things like this:

Who __________ (live) in Taiwan when it ____________ (colonize) by the Dutch?

Who had been living in Taiwan when it was colonized by the Dutch?

She looked at them and back and me and said, "Can we change the topic to the history of China?"

"Why?" I asked. "Is that what you're learning in school?"

"Yes! So I know that! I don't know Taiwan's history so well!"

"Well...no. No we can't. That's another country - "

"Mm!" she agreed.

" - and while it's useful to know about the history of other countries, especially ones with some relationship to your country, it's also important to know your own history. So we're doing Taiwan."

Despite her protests, she basically got the questions right. Even the one about how 鄭成功 managed to sneak past the Dutch patrols and fortifications.

* * *

I took the bus home - it takes longer but it's direct. I realized I'd never listened to Timeless Sentence, Chthonic's acoustic album in its entirety, and it has occurred to me after meeting Chthonic frontman and super-cute legislator Freddy Lim recently that I should, so I thought that'd be a good way to pass the time riding through the streets of Xinbei and Taipei.

|

| Super Cute Legislator Freddy Lim and *me* |

Every song on that album - culled from their black metal work and arranged acoustically - explores some aspect of Taiwanese history. Freddy, and the band as a whole, are unapologetic Taiwan independence advocates. Some of the historical issues they sing (well, scream) about are obvious ("Republic born of PAIN!") and some are less so ("Who now stands before me like a ghost within a dream? When did come the day when things became not what they seem?")

As these songs played, the bus crossed Fuhe bridge into Taipei. The sun was out; I leaned against the window and watched as the green median spokes were overtaken - some half-eclipsed, some fully - by the shadow of the bus. I was sitting at the back, so just as the darkened green pillars reached me, sunlight broke out again and drove out the dark.

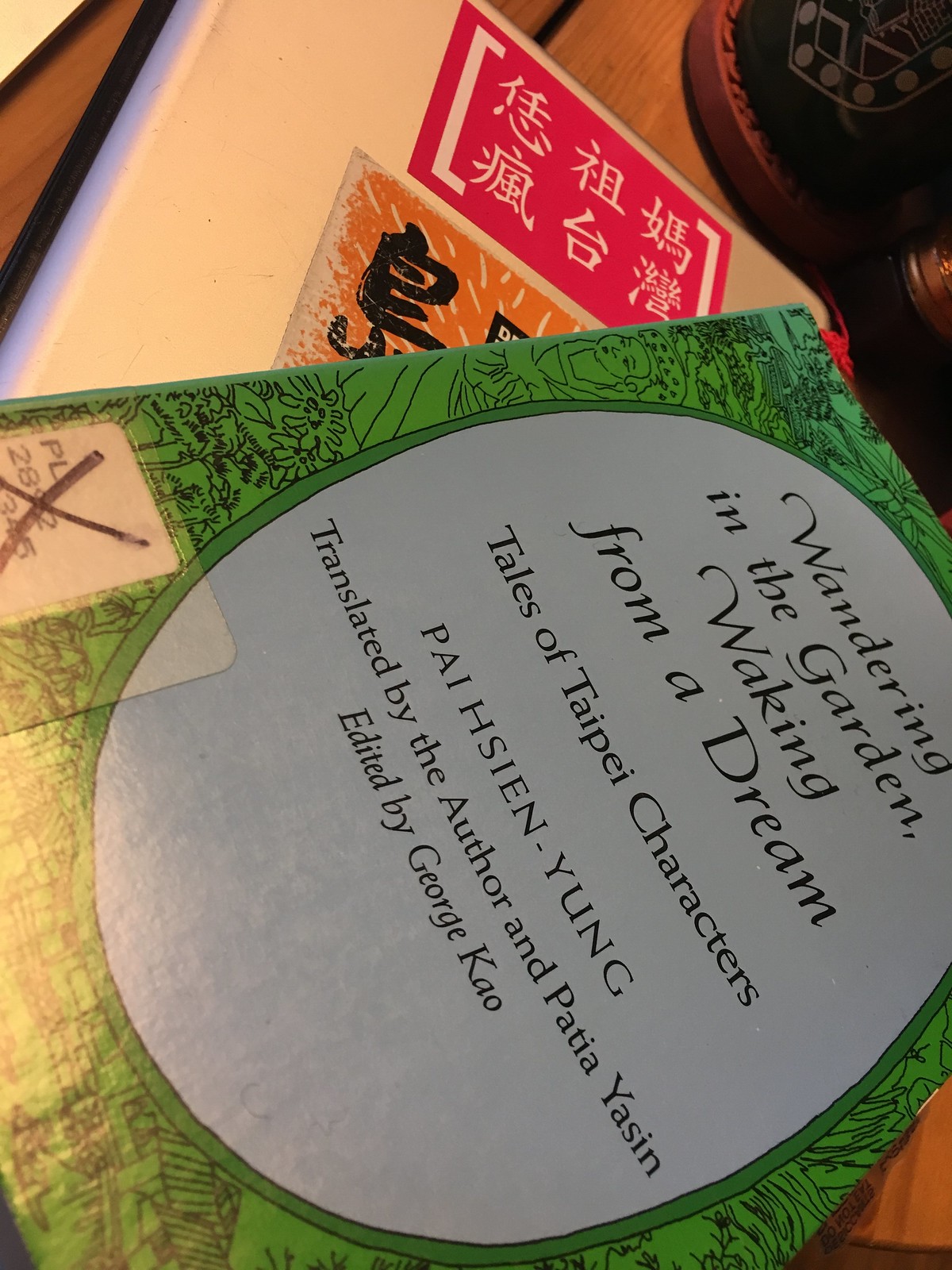

As I watched this, I thought to myself that when I got home, before I started work on a paper that was coming due, I should read one more story in Wandering in a Garden, Waking from a Dream. I'd been reading one a day as a break from academic work, and figured I could finish the whole collection fairly quickly.

I wasn't sure how I felt about it, though.

My main issue with Timeless Sentence is that Freddy is at heart a black metal singer. He is clearly going to some effort to re-modulate his 'voice' and 'style', and the layouts of the songs themselves, to fit an acoustic format. Sometimes it translates beautifully, sometimes less so.

I too felt I was having to reconfigure my mentality to read Wandering in a Garden, Waking from a Dream. I am used to reading about Taiwanese history from a Taiwanese perspective. I had to reformulate and remodulate in order to read without judgement stories of fictional members of the Nationalist diaspora in the 1940s.

* * *

The foreword makes it clear: although the original title of this anthology of character studies was Taipei People (台北人), the people in it are not from Taipei. They live there, but every last one was a refugee from China in the Nationalist diaspora of the 1940s. Most of them didn't seem to really consider Taipei home and every last one identified with China, not Taiwan. The newer translation, then, is perhaps more accurate: Taipei Characters.

Each of them confronts - or refuses to confront - memories of their life in China and squares them with their new lives in Taiwan. Some do better (Verdancy Chu in "A Touch of Green"), some worse (Yu Chin-lei in "Winter Night"). Some describe the pleasant, idyllic, even luxurious lives these characters led in China (Yin Hsue-yen in "The Eternal Snow Beauty"), others discuss the horrors they encountered in the Chinese Civil War (Lai Ming-sheng in New Year's Eve ). Each one is searching for their own version of peace. Although it is not directly stated, few find it.

The foreword also makes clear that these character studies are meant to do just that: study characters. Think of it as the ROC version of Dubliners (which I haven't read - I struggle a bit with Joyce). Not draw conclusions about the good or evil of the Republic of China or its effect on Taiwan. It makes these refugees human and shows them trying to rebuild some semblance of a normal life in their new home.

The arrangement of the stories is important: it starts with young (or young-seeming) beauties, one of whom seems hardly to age, who is associated with the color white (a white sun on a blue field perhaps?). As the tales continue, the characters grow older, grayer. They get weaker. They grasp at what they've lost, making the same noodles except "not as good", coloring their hair or losing everything trying to bring back loved ones (the proprietress and Mr. Lu in "Glory's by Blossom Bridge"). They start dying, some sooner than others. The first three and last three stories drive it home: starting with imagery of fresh bright snow and then spring green, followed by tales of great battles fought by people who are now older and weaker, and ending with autumnal scenes of faded glory propped up by wealth, the onset of a cold, cruel winter and finally, a funeral, they echo both the rise and fall of the Republic of China and the creeping realization that the Nationalists' current, dilapidated state is permanent and will only further decay. This also echoes Dubliners, or so I am told.

I have a deep well of empathy for such situations: my own family was driven out of Turkey and then Greece - refugees twice over. For most of my life, these experiences were recounted by ancestors who held them living memory. Everyone has the right to leave dangerous, even life-threatening conditions and seek a safe existence elsewhere, to prosper and, if they wish, come to identify with their new home, as my grandfather came to identify as American. Similarly, although these characters are not real, their pain very much is.

And yet, I note that almost every time these characters interact with someone Taiwanese, they are snobbish and dismissive. Everything about Taiwan is inferior - the silks are coarser, the people more provincial, the weather worse, the food never quite as good. They treat Taiwan like a pigsty that they, high and low-class both, are forced to live in. They don't seem to realize that the people who are already here are people too, no less worthy of respect, and this island (this country) is their home, and it is beautiful if you'll just look. They don't see it, and they don't seem to be aware of exactly how their beloved Nationalist government treats the locals (as well as some of their own, although this is not mentioned in the book).

For every shadow cast on their lives, some of these "Taipei characters" cast shadows on the lives of others, and they don't even realize it. They keep to their own communities, denigrating Taiwan and yet acting as if they own the place - I can't help but wonder, if you hate this beautiful island so much, why do you insist it's a part of your country? - and as someone who loves Taiwan, it is hard to read.

This snotty condescension, this dismissiveness of Taiwan - I have trouble with this. My empathy shrivels a little, although not entirely. If the Nationalist diaspora wonders why it is not always fully welcomed in Taiwan, perhaps this attitude - which I have no doubt was very much real - is a part of why.

There are exceptions: the narrator in "Love's Lone Flower", who spends much of her time with two Taiwanese characters, Peach Blossom (with whom it is implied she has a relationship) and Third-son Lin, and does not appear to judge them in this way. In fact, the most empathetic of the Taipei characters are the lower-class ones: the taxi dancers (although Taipan Chin in "The Last Night of Taipan Chin" is dismissive of Taiwanese taxi dancer Phoenix, in the end she helps her as best she can), the winehouse girls. They seem to make local connections that the former high-and-mighty do not. I can't expect they would have necessarily known about the white terror their white sun government was inflicting on Taiwan. They're just doing the best they can, and they too have scars. My empathy grows.

The army veterans, the generals, though, perhaps the wives of those generals - they must have known. Some of them, if they were real people, would have been a part of it. My empathy shrivels. Let them break down and die. They consider themselves Chinese, so why should we let them have governance of Taiwan? Why should the Taiwanese have to live under a foreign government they never consented to? Don't we call that "colonialism"?

That said, every last one came to Taiwan's shores and built a life here, some more successfully than others. Although my circumstances were different - I'm no refugee - I did this as well. How can I - someone who would like to be the newest of the New Taiwanese - make any sort of judgements about who is and is not Taiwanese? This beautiful country has made it possible for me to call it home, and Taiwan is a settler state - who am I to say which settlers get to call themselves local? As far as I'm concerned, if you live here and identify with Taiwan, you are Taiwanese. These Taipei characters did not consider themselves Taiwanese, but many if not most of their descendants would. Maybe their grandparents weren't really "Taipei People", but they are.

That said, how many of the real-life people these characters are inspired by turned away when they knew what was happening? How many reported a neighbor or disavowed a friend? How many to this day remain pro-authoritarian, stalling Taiwan's reckoning with its history?

But then, how many might themselves have been victims of that same regime's purges of "Communists" in their own ranks? How many would have grandchildren who grew up supporting movements like the Wild Strawberries and the Sunflowers?

The key difference between my ancestors and the "Taipei characters" is that the latter dream about their lives in China lost, and are often disdainful of the island they now call home. My ancestors missed the home they lost, but never used that as an excuse to denigrate their new country.

* * *

I say all this, but I haven't even gotten into the historical and literary allusions strewn liberally throughout these stories. I have avoided writing about this, because I don't understand every reference. I write this review as a layperson.

In order to give this book the best review I could, I read as much about the book as I could find (unfortunately, the best source is incomplete - and the complete book is obscenely expensive). There is a lot to say about the title story, Wandering in a Garden, Waking from a Dream, in which the narrator, after literally wandering in a garden, watches her old acquaintances enjoy a party in a mansion decorated with luxuries old and new, some having aged and faded and some seeming young and growing more vivacious, but still clinging, like a dream, to their lives in China. The narrator, a widowed general's wife whose stage name as an opera singer had been Bluefield Jade, is as faded as her dark jade-green qipao. The host's little sister, who helps trigger a drunken memory to her own younger sister, is more vigorous than ever. There are young lovers torn asunder by beautiful younger sisters, a snow-cave like dining room trimmed with vermilion table decorations (the ice-box where the KMT's dreams lie frozen in time, splashed with blood?) and allusions to three separate operas: The Nymph of the River Luo, The Drunken Concubine and Peony Pavilion (especially Wandering in a Garden, Waking from a Dream from that story).

I don't know if I can even begin to break all of this down, and am not sure I should in what is meant to be a book review, so here are three quick takes:

The Nymph of the River Luo alludes to a young man's tryst not just with a goddess, but, by extension, the wife of the Emperor of China. There is also a strong implication that Madame Qian, the narrator and general's wife, either had an affair with one of her husband's subordinates, or wanted to (personally, I think they did), until her younger sister stole him away. Something similar also happens at the party taking place in the story's present.

The Drunken Concubine is about how favored concubine Yang Guifei prepared a feast for the emperor, only to find he'd visited another concubine instead. In jealousy she drinks herself into a stupor. Madame Qian, jealous, is also drunk - but feels it is her younger sister in the past (and her party friends in the present) who are responsible.

Wandering in a Garden, Waking from a Dream involves a young woman falling asleep in a beautiful garden and dreaming of a

All of this is quite fascinating, and I read this particular story several times.

But what really struck me was what Andrew Stuckley, in the link above, said about a story earlier in the collection, The Dirge of Liang Fu.

The two couplets in the study of General Pu seem innocuous enough, but call to mind an ancient story in which a leader needed to dispose of three great warriors who posed a threat to him. To do that, he offered two peaches, to be taken by the two best of them (there is an allusion there to the peaches of immortality). Of course, to take a peace was to show impertinence, but to not take a peach was also a great shame. All three killed themselves and the scheme worked.

In The Dirge of Liang Fu, the "peaches" are - according to Stuckley - communism (in China) and Westernization (from America). Each promises immortality, but each ends up killing you. To not take a peach is to fade into irrelevance, as General Pu has done.

"Hm," I thought as I read this. "I hadn't known that and I hadn't paid that much attention to the story the first time around. I definitely need to deepen my knowledge of Chinese history and literature."

But...

I live in Taiwan, not China. I spend my free time learning about Taiwan - Taiwanese history, Taiwanese literature. China is a different country. And yet, Taipei Characters is a work of Taiwanese literature.

I considered the Taiwanese students who regularly protest the "Sinicization" of history classes in Taiwan, prioritizing Chinese history - and implying that Taiwanese and Chinese history are the same - and demanding that more of Taiwan's own local history be included...

...oh.

In that moment, I realized how difficult everything really is.

How many of these Taipei characters - if they were real and you could ask them - would think Taiwanese history is Chinese history and would insist that the dichotomy my student and I perceive is false? How many would listen to Chthonic's Takao or Broken Jade, songs about the Takasago Volunteers (one small aspect of Taiwan's Japanese history which is not at all Chinese), and insist that it was the same history as that of a Republic that fought Japan as a mortal enemy? A Republic that still insists that it fought with the Allies to defeat Japan while governing an island that, right or wrong, fought on the other side? Who among them would insist that everything Chthonic sings about is both Chinese history and not as important as Chinese history, all in one ignorant breath?

* * *

Then, I thought back to one of the lyrics crooned in English on Timeless Sentence:

Let me stand up like a Taiwanese, only justice will bring you peace.

The Taipei characters were not at peace in part because there was no justice, in the end, for the wrongs done to them. But they seem blind to the injustices, like shadows, that their own government inflicted on the Taiwanese, as well.

I then recalled a minor sub-plot in Green Island, where the protagonist's father, after ten years' of brutal incarceration at the hands of the KMT for something that wasn't a crime in even the pettiest sense, can't help but suspect that his older daughter's husband - an ROC veteran from China - was reporting on him to the government. He wasn't - the spy in his home was his own son, and Dr. Tsai's son-in-law from China has suffered his own injustices and was just trying to do the best he could.

I know this story in my history too: the person who reported on my great grandfather to the Turkish government was another Armenian. The leader of the group sent to apprehend him saw who he was ordered to take into custody, recognized my great grandfather as his old schoolmate and they embraced as friends. He was never arrested - the captain was Turkish. Things are not always so cut-and-dried, the good or evil of a group is not so easily transferred to individuals.

Of course, Pai Hsien-yung understood all of this - and he was not uncritical of the "dreaming backwards" of his Taipei characters, their ignorance of Taiwan and their slow decay under a veneer of wealth. I mean, the collection ends with a winter night passed by two threadbare academics, and then a funeral. He took his own stabs at the white sun on a blue field. He knew that they not only were dreaming, but that it was time to wake up. I can't believe he wasn't also aware of the way their isolated, dream-like state affected the island they had fled to.

I didn't feel entirely comfortable reading Wandering in a Garden, Waking from a Dream, but I will say this: it is excellent, a masterpiece, and I am happy I read it.

No comments:

Post a Comment