A short post for a gray Sunday morning.

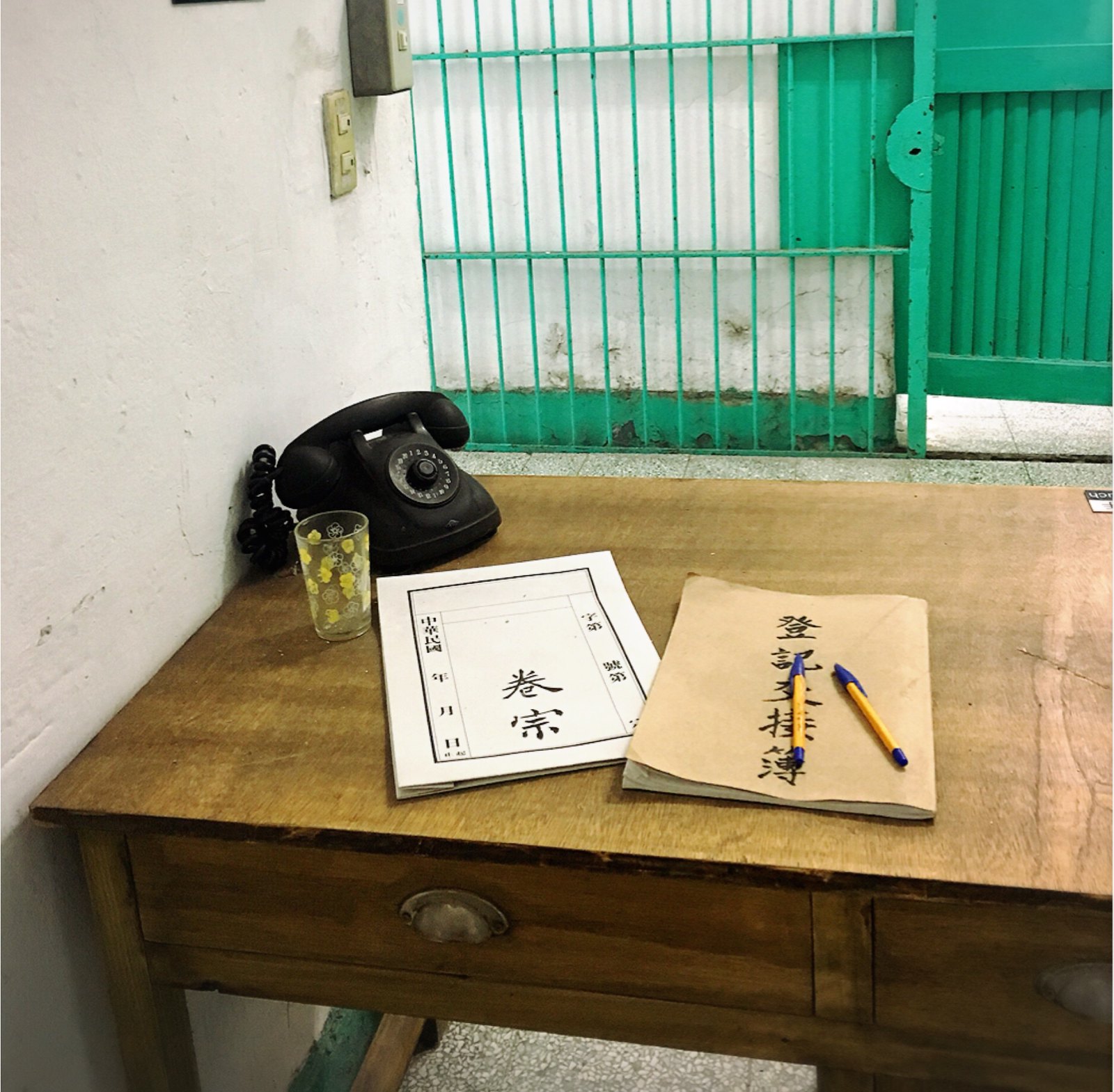

Yesterday, I visited the Jingmei Human Rights Museum (景美人權文化園區), which is a short taxi ride from MRT Dapinglin (大坪林) station (not Jingmei station, which is across the river near the Taipei/New Taipei border). The museum is a former detention center used to house political prisoners in the later part of the Martial Law era, along with the correctional facilities on Green Island. The original center was located in Taipei, but it was torn down and the Sheraton stands on that site today.

Alongside stories that make your skin crawl and your blood boil - that prisoners might well be executed with no trial whatsoever, that many still don't know why they were accused, how some were kept in prison long after it was known they had not committed the crimes they had been accused of (to "save face" for the officers), how they were housed thirty people to a 9 square meter cell and drink toilet water if there was no tap (and there often wasn't), and how only in recent years are some family members receiving goodbye letters, was a story that made me sit down and stare blankly into space for a time.

When inmates were allowed visitors - family only, no friends - they could meet for ten minutes at a time, and were only allowed to speak Mandarin.

Mandarin was not - and for many still is not - a native language of Taiwan. The KMT dictated that it was the official language of the ROC government they forced on Taiwan, and would become the lingua franca. This impacted education, government affairs (if you addressed the government - not that that ever did much good - it had to be in Mandarin), jobs (certain jobs were only open to Mandarin speakers, that is, members of the new regime and the diaspora that came with them) and more. At the Taiwanese who were already here when the KMT invaded - yes, invaded - generally spoke Hoklo and perhaps Japanese, Hakka, or indigenous languages. The native population of Taiwan was essentially forced to learn the language of the foreign power that came to rule them, and those who did not were punished either socially or overtly (anything from your neighbors suspecting you, to losing access to jobs and education, to actual fines and potentially arrest).

The purpose was, of course, not only for the KMT to force their language on locals (many members of the diaspora spoke Chinese languages that were not Mandarin). It was to remake Taiwan as a 'province of China', to erase its history and culture through erasing their languages. To stamp out 'Taiwaneseness', in all its varied linguistic uniqueness.

As you can imagine, some of the inmates themselves might not have spoken Mandarin well (perhaps some not at all), and it would have been fairly common that their family members didn't speak it, either.

What do you do when you are only allowed to speak a language you don't know when visiting a loved one you might not have seen in years?

"You can only look at each other, and speak through tears," said the tour guide.

A former victim imprisoned for a crime he hadn't committed joined us on the tour, and told his story as well: it included just such a scene, and he and his mother were not even allowed to hug. I won't narrate the entire tale here - that's his story to tell, not mine. (If you read Mandarin, you can buy his book here).

Whether such a cruel, inhumane policy was perpetrated out of a sense of 'practicality' - as a friend pointed out, the regime likely lacked the imagination to have Hoklo, Hakka and indigenous eavesdroppers ensuring their surveillance of prisoners was complete, or if they had thought of that, might not have trusted anyone to relay the truth. These are people who murdered without trial, who kept people they knew were innocent in prison to protect themselves - they placed their faith in no-one but their own (and often, not even then - many who came to Taiwan with the KMT ended up in prison as suspected Communists, as well).

Or it could have been simply because they were evil and cruel. Some of the former guards who are known to have tortured White Terror victims are alive today, living normal lives, facing no legal repercussions, seemingly at peace with themselves and their actions (though who knows).

I suspect it was a combination of both.

Fast forward to 2018: foreigners come to Taiwan to study Mandarin (though I haven't been particularly impressed with teaching methods here). I learned it so I could live here as normally as possible. It's seen as a practical language to know, something you might study out of interest, but is also internationally useful.

This history, however, and hearing it put so plainly, has made feel slightly ill about continuing to speak it in Taiwan. I'm not speaking a native language of Taiwan, not really - I'm speaking a colonial language. I don't feel good about that at all. I'd always felt a little unsettled about it, in fact, but that story pulled all of that nebulous uneasiness into sharp focus.

How can I speak Mandarin as though it is normal in a country where it was once used to keep parents from speaking to their children?

I'm aware of how odd that sounds - it is a lingua franca. Most Taiwanese, even those who are fully aware of this history, likely were impacted by the White Terror (or have families who were) and are otherwise horrified at the truth of this history, speak it - often without a second thought. Who am I,

Stripped of its dark history in Taiwan, Mandarin is merely a language. A beautiful language, even. One steeped in history that is otherwise no crueler than any history (though all history is cruel). And yet, it was used to brutalize Taiwanese - even now, those who do not or prefer not to speak it face discrimination and stereotyping, either as 'crazy political types' or as 'uneducated hicks', both deeply unfair labels that perpetuate a colonial system that dictates who gets to be born on top, and who has to fight their way up from the bottom.

Mandarin is only a native language and lingua franca in Taiwan because of this linguistic brutality. Foreign students only come here to learn it for this reason, as well. That most Taiwanese speak it natively speaks to the success of the KMT's cruelty. That not everyone does, and many who do still prefer native Taiwanese languages shows the strength of the Taiwanese spirit, and the KMT's ultimate failure as a cruel, petty, corrupt, dictatorial and foreign regime.

I can respect the idea that Taiwan has begun - and will likely to continue - to use Mandarin appropriatively rather than accepting it merely as the language of those who would continue to be overlords if they had their way. To take Mandarin and use it for their own purposes, to their own ends (this paper is about English being used in this way, but the main ideas are for Mandarin as well).

But - we're not there yet. There is still an imperialist element to Mandarin in Taiwan that makes me deeply uncomfortable. That structure still hasn't quite been broken down.

I know, especially as a resident of Taipei, that I can't just say "screw it!", refuse to use Mandarin unless absolutely necessary, and start learning Hoklo in earnest - preferring only to use that or English. Many former victims and Taiwanese deeply affected by this history do so, and I admire that, but I'm not Taiwanese.

I want to be a part, if only a very small part, of a better Taiwan, to contribute to building a truly free, decolonialized nation. But again, I am not Taiwanese. There are people who would think I was just putting on a show, and while I don't believe that, it would be hard to make the case that they are wrong.

And yet, the main reasons for not giving up Mandarin - that I would be giving up on something so 'practical', and that I'd be labeled another 'crazy political type' (perhaps more so because I'm not even from here, and this history is not my history), feel like giving the colonial ROC regime yet another brutal victory.

For now, I suppose I will keep speaking Mandarin; I kind of have to. In any case, is Hoklo not the language of oppression for Hakka and indigenous people? And yet, I don't see any sort of real world in which I can walk around Taipei speaking only Amis and a.) not look like an idiotic - if not crazy - white lady; and b.) actually communicate with the vast majority of people. As a language learner and foreign resident, where do I draw that line?

I don't feel good about it at all, however, and perhaps the first step is, without giving up Mandarin per se, to start seriously learning Hoklo.

No comments:

Post a Comment