This wasn't meant to be my next book review. It was supposed to be Social Movements Under Ma Ying-jeou, but I finished that the day before flying out for Lunar New Year, and didn't bring it with me. Being highly academic, it's the sort of book you need to refer to as you write about it, so that'll have to wait until I return to Taiwan.

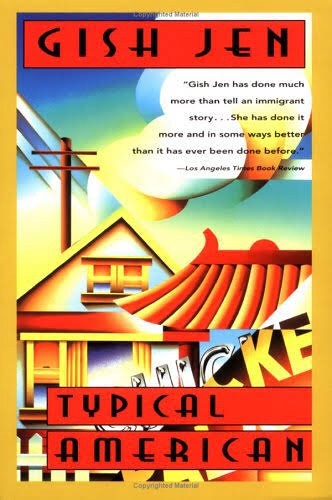

Instead, let me tell you about a book that's not about Taiwan at all, except that I think it sorta kinda is. I brought only fiction on this trip, including a book I'd picked up secondhand years ago, but never read: Gish Jen's Typical American. Having already read its sequel, Mona in the Promised Land, some years ago, as well as several of her other works and knew her to be an engaging author, so it was a solid beach read choice.

(Contains spoilers - for a book written in 1991, so you can just deal.)

Typical American begins in 1947 in a small town outside Shanghai, and ends in upstate New York not far from where I grew up. The son and daughter of a scholar and former government official are sent to the US under very different circumstances (because, of course, sons are so often treated better than daughters). Theresa, the cleverer of the two, accompanies the daughter of wealthy Shanghai friends, whereas Ralph is sent to graduate school for engineering. Then the Chinese Civil War takes a turn for the worse, their parents disappear, Ralph marries Theresa's companion, Helen. They meet wealthy yet ultimately deceptive Grover Ding and staid, old fashioned Old Chao. They live together, then apart, then together again.

Taiwan isn't mentioned once (though the Nationalists are; of course the Nationalists and Taiwan are not the same things). But, in a way, it was.

I don't know if this was Jen's intent, and it was written too long ago - 1991 - for me to feel anything but awkward about asking her. But I can't help but see an allegory well beyond "family from China finds its way in post-War America and has its own experience with the American Dream". But reading some of the language used, which could not have been unintentionally chosen, I have to wonder.

Think of Old Chao as, well, the well-worn traditions of "ancient China" (his name basically means "Old Dynasty", or is at least a sort of homonym of it, as I don't know what the character would have been.) Now see Grover as everything corrupting about US influence (in terms of culture and family life, but also, perhaps, in terms of international relations). Theresa, a woman born "outside of her time", represents the Republic of China and the hopes leaders had for the Republican era in China. Helen is everything dainty and refined - but also resourceful and plucky - about early twentieth-century urban China (Jen all but says so explicitly on this point). I'm not sure what that makes Ralph, or Old Chao's wife Janis. But I have to say, Ralph's Chinese name - Yi-feng or "strive for the peak" - can not only represent struggling to attain the American Dream but also echoes a lot of language choices of Communist China.

Okay, so what? Well, Ralph, Helen and Theresa live together at first somewhat peacefully. They are friendly with Old Chao, then Grover Ding throws a wrench in their lives. Theresa moves out angrily - Jen even calls it "exile". When she moves back in with Ralph and Helen - a "reunification", and calls it the hope of all Chinese people (though she doesn't entirely use those words, "reunification" is straight from the text. This cannot be a coincidence.) At several points in the text, ideas like "once a Chang, always a Chang" and the custom of Chinese families to live together in sprawling compounds are referenced, as how difficult it is for families to splinter and then reunite. That things change and cannot go back to anything like they used to be after a "reunification" (both sides change) also whizzes by readers who lack contextual knowledge. In between, various characters get involved with, then extricated from, then re-involved with Old Chao and Grover. Ralph abuses Helen, Old Chao seemed associated with Ralph but turns out to be most closely tied to Theresa. Ralph either proclaims the house they live in is "his" - he's the "father" (you know, like Confucius) - but at one point realizes it is actually Theresa's (don't ask why; read the book).

Do you not see it?

Maybe I'm insane, but I see it.

I don't like it.

Don't get me wrong, I loved the book. Read straight as a coming-to-America tale and how cultures collide when immigrants chase a foreign dream, it is engaging, thoughtful and mesmerisingly written. The prose draws you in and is elegant both in sound and how it falls on the page. Structures - houses, restaurants - serve as visual symbols for the state of the family. Old books in Chinese make an appearance, as does the game of 'bridge', a loveseat (you know, where love sits) and more. And, for fans of Chinese idioms, the moon makes several appearances in the narrative. You know, in America. A foreign moon. The moon is sometimes big and round as the idiom suggests, sometimes a sliver of a nail.

But...that other narrative, the one I might have just spun out of my own Taiwan-evangelism.

That one? It glorifies the Nationalists (I assume Jen is aware of their treatment of Taiwan - the theft of Taiwan's wealth, the White Terror, the oppressive and murderous military dictatorship that differed from Mao's mostly in scale). If you read the symbolic elements as I did, it treats the US's severing of recognition of the ROC as a tragedy, not unlike being attacked by a dog and hit by a car. (It was a tragedy, but for reasons nobody realizes; the way Chiang Kai-shek screwed Taiwan out of United Nations membership, the way US foreign policy at the time made sense, but in the decades following did not adequately address Taiwan's democratization and more open recognition of its own unique cultural identity).

It assumes that there are two sides in this conflict only: the Nationalists and the Communists - that Taiwan as a unique place that had a unique population long before Chiang started crowing about "retrocession" let alone before his government took the island, or he himself set foot on it - simply doesn't exist, or matter. That there is no unique Taiwanese cultural, historical and political identity distinct from China's.

That "reunification" can not happen - because the two sides that would supposedly 'reunify' had never actually been together (Qing imperialism should not count.) It assumes that Chineseness will mean that, while there might be conflict and a future very different from the past, that these differences have some hope of being bridged. After all, they're all part of one sprawling household, aren't they?

Except they're not. For that take on things to work, both sides have to agree that they are more alike than different, that there is some ineffable "Chineseness" that ought to bind them.

Forget what politicians have to say to avert a war. Those are words stated at first under a dictatorship, at the tail end of Martial Law, by a government the Taiwanese people had never asked for. Now, they are words not denied under threat, nothing more, though that slowly seems to be changing. Finally.

Do not think that the people of Taiwan believe this. They haven't, for awhile. If you are going to reify 'one Chinese family' as a cultural structure, then everyone in the family has to agree they are in it, and want for that family to be 'reunited'.

But they don't. They haven't, for who knows how long (pre-democratization public opinion polls are suspect at best; remember what kind of education everyone got. It's very difficult indeed to grow beyond what one has been told all their lives. It's a miracle and a credit to Taiwan that they have done so as quickly as they have.)

In this sense I have to hope that Jen did not intend Typical American to be read this way; that I'm adding all of this in because I'm just nuts. After all, the story is not that different from Jen's parents', just as Mona in the Promised Land is clearly heavily influenced by her own formative years. It could be as simple as that. But Jen produces smart, layered work - so it's possible. If she did, it might represent a nostalgic view from a Chinese perspective, but it belies a lack of understanding of Taiwan.

If true, this isn't terribly surprising, and isn't Jen's fault. She's not from Taiwan; she was born in the US to Chinese parents. I have not heard that she has spent any meaningful amount of time here. Why would she have insight into the Taiwanese collective psyche? What's more, Typical American was written just before Taiwan's first true - though tentative - steps towards democratization. Nobody without a connection to Taiwan was talking about Taiwanese identity then. So, it's hardly surprising that she focused on history more immediately familiar.

So where does this land me? Hoping that a book is less deep, not more? Enjoying it for what is immediately clear on the surface, and hoping there are no weeds or sharp rocks lurking below on which my feet and her story might become entangled or scraped?

I guess it does.

No comments:

Post a Comment