Here are the things that swirl around my house and my head: it's the middle of the night, and I've taken the upper amount of anxiety and sleeping medication indicated by my doctor. My body is asking for more if it's to sleep, which I cannot give. Ambient light from outside provides just enough to navigate by, but no more than that.

Laptop in my lap, because I touched the black mound on my coffee table and it answered me with an annoyed prrrt. He's not supposed to be on the coffee table. Oh well.

I am still angry to my core; I didn't know I had an aquifer of rage so voluminous. It's not that I was unaware that horrific injustices worse than the loss of Roe v. Wade happen around the world frequently; of course I knew that people in the US and beyond have been fighting them for longer than I've been alive. I thought, especially for Taiwan, that I had been regularly tapping into that cold, clear fury. I, too, am surprised it runs deeper. I suppose this is the difference between being an ally and being a person directly affected. (Even though I'm safe as a Taiwan resident, I'm still a US citizen with a uterus that is probably capable of bearing children.)

This is affecting not just my sleep, but my work and life. It's a vise of anger during all hours, productive and not, that the infuriating debate over which human rights I get to have, and which I don't because I was born with complicated innards -- as decided mostly by people with different, simpler innards -- has even more real consequences.

It clarifies a lot, realizing that the people out there who thought they had an honest argument for why you are more of an egg sack than a human actually won something. But then the whole room fills with smoke.

While trying to manage my ire from Taiwan -- where I'm not of much help, but have been hunting for and donating to various sources -- I've been confronted with a more troubling self-truth. So many of the dark thoughts I know I should be managing, as I did during my first anxiety outbreak in 2020, aren't going away. What's worse, that's very clearly because I do not want them to. I won't detail every violent event I've imagined celebrating (most of them circle back to Molotovs; it's actually rather boring and repetitive -- Molotov this, Molotov that, you know, the usual).

It is hard to focus beyond this shrieking wall of inchoate rage, to try and envision a world I don't want to burn to the ground. Yes, a single court ruling taking away my basic humanity in the country of my citizenship turned a boring center-left normie lib into a flaming anarchist.

But I don't want to talk about that. Too much, anyway.

Instead I'll focus on a deeper intransigence -- family.

Friends and social media connections are easier to deal with -- if one supports the hijacking of a uterus for any reason, in ways we don't even violate corpses, then it's blammo for you. Get out of my life; we are not on speaking terms.

Family, though?

I love them very much. Many of them, I know, understand the importance not just of a woman's right to privacy and choice. Many understand that even if you support your loved ones, if you vote for people who will hurt them -- officials who have made it their life's work to do just that -- your support is shallow and hypocritical.

Others, however, are less clear. People who have always been good to me, but drop hints that they voted for Trump, don't think I deserve full humanity as a woman, people who love me because we're related but genuinely wish that someday I will understand that God is real, and he prefers that women have subhuman status, not equal rights.

Of course, I will never understand that because it is not true.

I do not know who believes what exactly, because I'm afraid to ask. I have made it clear that I do not wish to be on speaking terms with anyone who thinks it is acceptable, should the circumstance arise, to force me to give birth to a child I do not want. But I'd prefer not to directly tell family members I care about that I cannot speak to them -- not until the federal law changes, or their opinions do. It would be fairly easy from Taiwan; I don't visit the US much anyway, and these are all extended family. It's hard to pull that plug, though. I both comfort and torture myself with the realization that they probably know exactly how I feel.

There is nothing in the modern world that offers respite, let alone answers. The drugs don't make me worse, but they certainly don't work, either. So, of course, I turned to a book I cannot read.

Last month, my immediate family and I spent a week cleaning out a packed storage unit. Inside were a stack of my great grandfather's books, mostly in Armenian. I asked an Armenian genealogy group to help translate the titles, and most turned out to be somewhat bland ecclesiastical reference materials. A plain brown tome simply called "Sermons" by a man surnamed Papazian. "The Radiance of the Bible" had a straightforward image of a Bible surrounded by light rays on the cover. These stirred no feeling, and I set them aside. A few I kept, even though I don't read or speak Armenian: most were cultural histories, one had stunning illustrations.

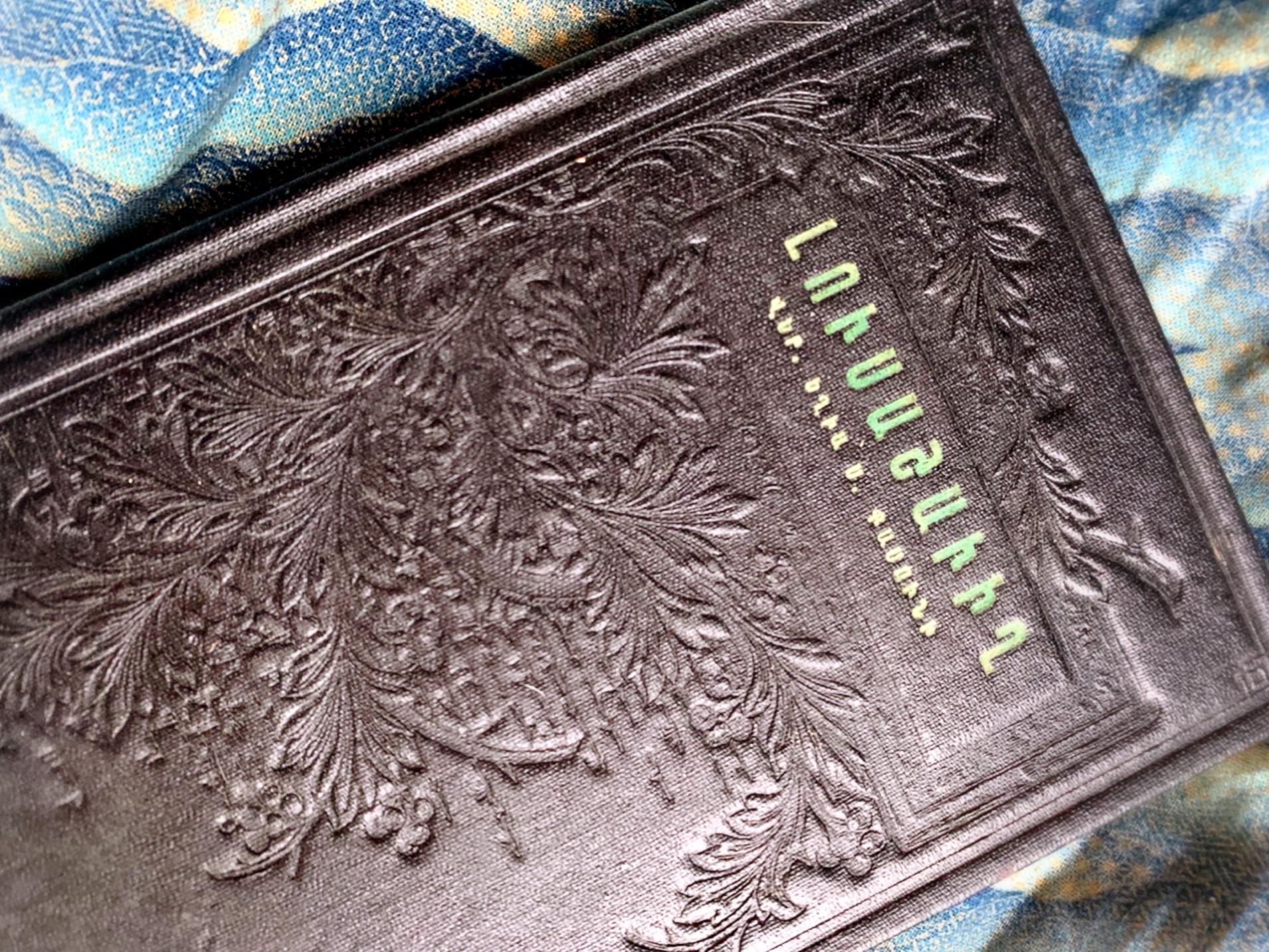

The only religious title I kept was The Light Generation. It's a history of the Armenian Evangelical Movement, bound in dark leather decorated with swooping floral patterns.

I wasn't attracted to it just for the cover: I'd already started playing with the words. The Light Generation. The Generation of Light. The Lightweight Generation, floating away like spent dandelion puffs as the diaspora spreads. A Generation of Lightweights, unable to fight as their descendants would for what is right, instead clinging to batty old conservatism. Or maybe we're the lighter generation; after all, they survived a genocide.

The Generation of Light -- the light we make. Things are dark now, but we can generate light. Our generation can bring it forth. Or theirs did: maybe they were the Light Generation -- the light needed for their times, not ours -- and we have the Sisyphean task of finding our own light.

I can't read a single word of this book, much as I never had the chance to meet the man who owned it, and was too young to appreciate growing up with his widow, my great-grandmother. It's on my bookshelf all the same.

In the past year, I've been working through some heavy mental stuff by finding connections to past and family through amateur genealogical research. It would be a lie to say I haven't begun to write about it as well, but I'm unprepared to discuss the type and extent of that writing just yet.

I can say this: people from the past are so much easier to work with. Most likely, I disagreed with almost all of them on social issues, perhaps even more strongly than I'd disagree with my conservative relatives now.

But they are gone, and they did things I will never do. Surviving a genocide, watching your father led off to die, engaging in vigilante justice against criminals in your village, leading a church, raising three children, emigrating as refugees to the United States, rebuilding a family separated for months by arbitrary quota systems. Bringing their lives and images back into a living person's memory means I can accept that they (likely) believed things I wound find abhorrent, but I don't have to have a conversation with them, and considering their historical legacies in their own right is worthwhile regardless. It's a route back to family when I am not sure what extended family I can actually talk to right now.

Certainly my mind could use the generation of some light. Rather like the dark living room, made moodier from the cool blue screen of a computer that should not be open, I don't know where to go from here. I've donated to all the resources, rage-posted for days straight. I don't know that any of it generates a speck of light. Maybe I'm a lightweight. I feel like I generate nothing; my generation has nothing.

Another book on my shelf (A Latter Day Odyssey by M.M. Koeroghlian) describes the ecumenical questions that beset the Armenian Evangelical Church in Athens, during the time that my great-grandfather worked there. The seminary and church community was plagued by dissent for a time, between conservative "mainline" types who believed in "simple" faith. That is, dogmatic faith in which a religious teaching is true because it was revealed to be true through miracles and scripture by in some way by an interventionist God. Believe in that God and his "miracles" and your path is correct. Do not ask questions.

These mainliners were worried that the School of Religion was teaching more "modernist" scripture: deist views eschewing 'revealed truth' and associated miracles, pointing instead to an innate knowledge of right and wrong in everyone, through which an understanding of God could be found through reason and observation of the natural world. Not religious strictures handed down by an angry God who blesses and smites, but moral guidance woven into the natural way of things.

Theoretically, according to this philosophy, even non-Christians could be good people worthy of Heaven if they understood and followed these natural laws. (I suppose these pastors felt it would be better, however, if the non-Christians converted.)

Despite my own atheism, given what I know of my great-grandfather's personality, I have every reason to believe he was more of a modernist, not someone who put much stock in miracles or dogmatism.

As an atheist, I don't really believe in any of this, but there is some room in my thoughts for natural law and ethics. Of the schools of Christian theory, this is one of the least offensive. For what it was at the time, I can say it generated light.

Of course then, the question is: which ethics are natural? Would these enlightened Christian modernists of the early 20th century now accept that women's bodily autonomy is a fundamental human right, to be protected at any cost?

I doubt it.

But they probably would have believed that, even if a woman terminating a pregnancy ought to feel sorry for her "sin", that God would not smite or strike her or anyone over it. No cataclysms. No disasters. Just a choice she made, for which only God could judge her.

I don't believe this either, as it is quite plainly not ethically wrong to terminate a pregnancy. It is ethically wrong to deny a woman her humanity, even for a moment. There is no special case that changes this natural logic.

They likely wouldn't have agreed with me. But their light generation has passed, and mine is alive. If they believed an appeal to reason and natural law would return sufficiently consistent ethics across vast swaths of generational and cultural shift, they were mistaken.

This story is a difficult one. The road to the past is complicated, and in parts I have to fill in what I think happened. It's not so simple as saying I'm mentally sinking, but seeking solace in the stories of the past. I don't agree with everything those from the past would say. I'm not yet uplifted. I do not float.

But maybe the modernists of the past would be able to grasp that cultural norms do, indeed, change over time. That if nature reveals truths to us through reason, that our interpretation of that reason would certainly change as our society does. That what was seen as "good" or "right" in the past may not be now. And perhaps that the god (and the good) they believe in simply would not want women to suffer and die.

I don't know what The Light Generation says about any given generation in the history of Armenian Protestantism. Even if I were religious, I can't read or speak Armenian, so I doubt I'll ever read it. I don't even know if the title, in its original language, allows for such wordplay: Armenian is an Indo-European language, but it sits on a lonely branch. I do not know if generation can have two meanings in it, just as I don't know if those who once read it would think I'm improperly using their stories, or updating them for a new era.

But I have decided that every generation has the opportunity to be the Light Generation. Generating light isn't hard; some moral questions are complex, but some are quite clear.

In this case, uphold women's unquestioned equal access to human rights at all times -- in fact, anyone's equal access regardless of their reproductive organs -- with no exceptions.

Maybe it's just a thread to hold onto -- long-dead ancestors who can't talk back, when I'm not sure who I can speak with alive. I can't even say it will be a useful road to get my own mind out of the dark pit of unmitigated fury, to a place of light generation. Perhaps it will.

Or perhaps not.

You know, it is possible to learn Armenian. Free courses here (Western or Eastern):

ReplyDeletehttps://www.avc-agbu.org/

I've been learning Eastern, but know some sources for Western if you're interested. It'll be a while before I can make any sense of ԼՈԻՍԱՋԱԻԻՂ, though! ("Luys" or "light"--as in luminosity, not weight--is spelled differently in Eastern.)

That is good to know. But I'm very picky about pedagogy -- I'm a social/experiential learner. I learn by doing, by actually communicating. I could take a course but I don't know that it'd really sink in until I could routinely practice conversation in Armenian, which seems impossible. For Western it's even more dire; at least there is a country in the world where, if I wanted to learn Eastern Armenian, I could move there. For Western? It's a diaspora language. True fluency was probably lost to me the moment my grandpa decided not to teach his own children.

ReplyDeleteIn that case, you might consider studying Eastern first, then after a year or so, learning the differences with Western. I'm enrolled in the second term of Eastern through AVU, which has lots of communication activities such as game-like exercises, and Zoom sessions with a teacher (yes, time zones are an issue). And I would be happy to practice with you!

ReplyDeleteI recommend starting with these 12 Peace Corps language videos. They're very good--they're about 12 minutes each, and not difficult. They teach the alphabet, basic greetings, some very fundamental grammar, and numbers. They're in Eastern, but most of the material will transfer over to Western, and the differences won't do you any harm! Just watch each of these again and again until you remember everything, then proceed to the next one. Peace Corps volunteers are supposed to work through them before they arrive in Armenia, and then afterwards go through an intensive course. Here's Lesson 1:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hcsFtGZv5sI&t=2s

I won't say that Armenian is easy, but it is not as difficult as you may be thinking (you can do it on a break from Chinese!), and studying the language has given me great pleasure and satisfaction. If you can draft your husband into watching these videos with you, and make a contest of it, then presto, you've got a language partner! (Alas, my wife resists.)

Write me at beidawei@mail.ru if you like.

Well, when I say communicative, I mean authentic communication (including conversation) with real speakers, either other students or native speakers. Games have their place, but my whole deal is more social constructionist and discourse-based. Zoom sessions with a teacher are great, but research shows (and I know for myself personally) that one learns best when paired with lots of different communication partners (this is one reason why I am wary of one-on-one lessons except at very high levels). But, I have been thinking recently to maybe at least learn some basics, acknowledging that I will probably never, ever be actually good at any kind of Armenian. I doubt I'd even get to the point where I'd learn much about Eastern/Western differences because the way I'd do it would not be setting me up for the sort of fluency I'm after.

ReplyDeleteFor example, I studied French for over a decade in a traditional classroom setting. I wasn't bad at it, but once I left that setting, I forgot it very quickly because no fundamental automaticity had been fostered. Now I can kind of read but not speak at all. With Mandarin I've barely taken any classes but I have the sort of baseline fluency I need to not forget, because I learned it the way *I* learn -- among others in an authentic setting.

If the choice is between YouTube / AVC Armenian, and no Armenian at all, well, as they say, "the best is the enemy of the good!" And maybe eventually you could find some way to spend more time in Armenia (perhaps after Taiwan gets invaded!).

ReplyDeleteAs for arranging for multiple communication partners, hmmm. If only there were some kind of "Armenian Community of Taiwan" type organization, like the opposite of this one...

https://www.facebook.com/groups/chinahay/

But for that we'd need at least two people, like in that famous Saroyan quote.

("Formosahay" is taken by some Argentine group, "Formosa" being one of their provinces.)

On language study, I remember growing up thinking that linguists should never be allowed to write language books, because I'd want to learn how to say "hello" and count to ten, and they wanted to write about morphology and phonology and stuff like that. But I gradually learned to adjust to their weird customs, until eventually the natives accepted me as one of their own!

But seriously, give it some thought. It sounds like you are being spiritually drawn to some sort of deeper connection with the hayrenik (wherever located), as am I in my own way. Don't be deterred by these obstacles, or by your own doubts. The years will go by, and then...either you'll have learned some Armenian, or not. So which future do you want to live in?