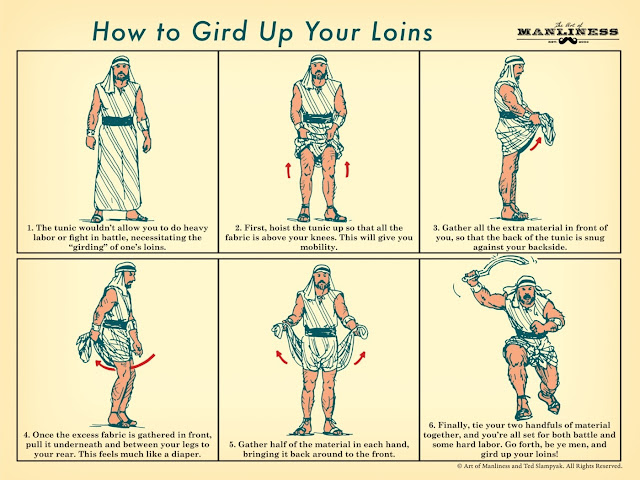

Yes, yes, this picture is meant to be tongue-in-cheek (or tunic-in-loins)

Recently, political scientist Nathan Batto wrote about youth turnout in the 2020 vote on his blog, Frozen Garlic. He speculated that gender might be an interesting area to explore in voter differences, as women tend to support the KMT more than men by a surprising amount:

Newcomers to Taiwanese politics are always shocked that women are about 5% more pro-KMT than men since the much-publicized gender gap in the United States favors the more progressive party. My suspicion is that older women are much more conservative than younger women (ie: the age difference for voting behavior is much larger for women than men), but I don’t have any hard evidence of that right now.

This seems likely. The youth surge in 2020 was overwhelmingly pro-DPP -- men and women both. Women might support the KMT at a higher rate than men overall, but that doesn't mean a majority of women support the KMT. This all points to a difference in beliefs between younger and older Taiwanese women.

Like Frozen Garlic, I don't have any hard evidence either, but that won't stop me from throwing the nerdblogging equivalent of a kegger to explore the topic.

Although the main cleavage between the two parties is still China, these days it's not ridiculous to consider the KMT the more socially conservative party and the DPP the slightly more socially liberal one, in some areas. (Marriage equality? Yes! Labor rights? Not really.)

Beyond a little speculation that older Taiwanese women are more likely to be KMT voters (and more conservative) than younger ones, Frozen Garlic stopped there. Freewheeling political analyst Donovan Smith agreed with him, and pointed out that he was in a position to speculate wildly about why this might be (but refrained from doing so).

I also tend to agree, and because I'm literally just a hobbyist, I'm at liberty to go hog-wild and talk about why.

Of course, a full and reliable answer would require real research. I'm not in a position to do that research, so the best I can offer is Lao Ren Cha Gone Wild.

So if you think Donovan is free to "speculate wildly", then when it comes to me, grab your tunic and gird your loins because here we go.

Let me lay out the few key points before we begin.

First, that (admittedly imperfect) parallels can be drawn to the political histories of other countries.

Second, that higher KMT support among women probably is driven by older women, and this has a lot to do with intentional targeting by the KMT on many fronts, over several decades.

Third, that the opposition which coalesced into the Tangwai and DPP was not necessarily friendlier to women than the KMT in the early years, and the feminist movement's initial aim for political neutrality meant that they were not a direct conduit turning women to the DPP. In fact, the Taiwanese feminism of the 1970s was, by today's standards, simply another flavor of conservatism.

And finally, that while there is a lot of overlap between social conservatism and KMT support, there are also areas of divergence -- women might support the KMT or DPP for their own reasons, which may not intersect entirely with where they fall on the spectrum of social liberalism/conservatism.

Even more importantly, I'm not attempting to explain why all women who support the KMT do so. There are many reasons, motivations and interplays of personal preference and societal conditions. The best I can do is offer a few reasons from history on why women support the KMT at a slightly higher rate than men.

I am not a Taiwanese woman, however, so I can't claim to speak for them. I suppose I count as "older" now, but I'm younger than the women I'll be discussing. I've talked with a few local female friends about this, even though they aren't KMT supporters themselves and also cast a slightly broader net, which resulted mostly in articulations of the varied reasons why individual women support the KMT and further speculation that this was almost certainly driven by older women. Women I spoke to cited their mothers, grandmothers or aunts, not themselves. This is not the same as actual research, but insights from those conversations have informed my own analysis.

This is a (somewhat) global phenomenon

The reason why (I think) older Taiwanese women are likely more conservative than younger ones, and thus possibly more likely to vote KMT, is that this is not a phenomenon unique to Taiwan. Older people, in many countries, to tend to vote for the more conservative party than younger ones. The US and UK are clear examples of this.

Research shows that political views don't tend to change as much with age as folk wisdom indicates, although if this does happen, the trend is toward conservatism. This may be the by-product of what generation one was raised in. In other words, social norms tended to be more conservative in the past than they are now, and people stick with what they know. There's no reason why this wouldn't also be true for Taiwan.

Of course, this trend doesn't necessarily hold outside the West. South Korean youth have helped propel center/liberal-leaning parties to victory, but they tend to turn away fairly quickly and young South Korean men are much less likely to support them. In Japan, the youth seem to trend conservative. However, when comparing democratic systems, it seems to me -- again, wild speculation time -- that most Taiwanese would be as or more likely to measure their country against Western democracies than neighboring ones.

If I'm right, there is surely a discussion of white supremacism and cultural imperialism to be had here, which could be its own post. However, it's also important to point out that Taiwan also has historic reasons to look westward, as its friendliest ally has generally been the US (despite some, well, bumps), and biggest neighbor has always been openly hostile.

You might be thinking, okay -- but what does this have to do with older women? Aren't we talking about the gender dimension?

Yes, but the same holds true. Although women identifying with the more progressive party holds true across generations in the US, younger women are far less likely to be conservative than older ones, and white women are more likely to be Republican, period.

What's more, research also shows that while women across all age groups tend to be more liberal than men, that the tendency of older voters to be more conservative still holds.

Although British women were once more likely to vote conservative than British men, that's changed in the past few years, and younger British women are more likely to vote Labour.

In other words, the notion that women will be more likely to support the "more progressive" party because that party is more likely to advocate for their interests doesn't actually hold up when you look at the details. Women are not a bloc: they're divided by race, class and age. If that's true in the US and UK, why shouldn't it be true in Taiwan, as well?

Authoritarianism is also anti-feminist

In Women's Movements in Twentieth-Century Taiwan, Doris Chang beautifully lays out the women's movements women from these cohorts would have experienced. You can read a summarized version of much of her work here, with institutional access.

Essentially, although autonomous (not government-controlled) women's associations existed in Taiwan in the Japanese era, and in China, the May Fourth Movement also held a more liberal ideology toward women's place in society, these events are now almost entirely beyond living memory.

Japanese-era attempts at organizing women to fight for equal rights were of course washed away by the arrival of the KMT. For the May Fourth Movement, these ideals were intentionally attacked.

I'm going to quote at length here because not everybody has institutional access, and I'm going to lose my own access soon:

From 1927 on, radical women, including feminist women, were under attack not only from conservative elements in Chinese society generally but also directly from the Kuomintang....

In the 1925-1927 period....the left wing of the KMT trained women organizers, set up women's unions, provided marriage and divorce bureaus, and educated local women in the meaning of the revolution. Several hundred women were trained to work as propagandists with the army. But after Chiang's coup, these women were in direct danger. Only a handful of the top leaders were able to escape the purges that followed....

In early 1934, Chiang Kai-shek launched the New Life Movement from his Nanchang headquarters....With the endorsement of the national government, the movement spread and became a part of the official ideology....It was at this time that Chiang looked to Germany, rather than the Soviet Union, as a model....The new order of fascism, with its emphasis on military power and total control, struck a chord of response within the KMT. So too did its emphasis on the patriarchal family and male supremacy.

This destruction of the left wing of the KMT by the right had a great effect on the course of women's issues in Taiwan after the KMT's arrival.

Neo-Confucianism and the New Life movement imitated a sort of modernism and claimed to promote greater civic participation, but were fundamentally illiberal, tradition-oriented and, as some have speculated, fascist, and this greatly affected the nature of the women's associations promoted by the KMT.

These associations were spearheaded by Chiang Kai-shek's wife, Soong Mei-ling -- if not as the founder, then as chair. Her Christian views, which were not incongruous with New Life, likely also played a role. (In fact I've often wondered if that's the reason why there are so many churches on Xinsheng 新生 -- New Life -- Road.)

These included the National Women's League 婦聯會 (which I believe is the same as the China Women's Federation, but please correct me if I'm wrong) and the Women's Union, established by a KMT committee. There was also the exclusionary International Women's Club, open only to elites.

Soong Mei-ling might have chaired women's organizations but she did not fight for women's rights. (From Wikimedia)

Soong took such initiatives because allowing "civic society" to exist was considered important to prevent (more) rebellion against the authoritarian KMT, but only if the government was solidly in control of them. The idea was to promote civic participation, but in a pro-establishment way.

Soong's women's associations were organized around supporting the nation -- the Republic of China, not Taiwan -- and the traditional duties of home and family. They promoted motherhood, domestic sanitation and "being a wife that a husband can rely on, so our soldiers can keep on fighting".

These organizations were designed to prevent women's movements from gaining a political voice, and to keep women in traditional roles, not to help them speak out and break out. Explicitly founded on the illiberal ideals of New Life, there was no chance of any sort of reform or women's equality movement arising from them.It's no surprise that many (though not all) of the women raised in such a society would have carried the echoes of these social norms from their younger years as they grew older. Surely there were women who disagreed with the roles society had given them, however, whether they were from Taiwan or China, they would be aware that the punishment for vocally dissenting from these prescribed norms was, at best, government scrutiny and at worst a trip to the prison at Green Island.

Did this attempted social control create women who were more conservative than men? It's difficult to say. I do think, however, that it influenced a few generations of women t0 be more likely to remain loyal to the KMT.

As far as I'm aware, there was no China Men's Federation / National Men's League. Women got their own group because, despite being half the population, they were Other. Within the greater attempt to subjugate society, there was a targeted attempt to subjugate and control women.

This sounds like a fantastic way to get women to hate you, but that's probably not what happened.

These women's associations put a friendly face on the underlying misogyny: spinning acceptance of male supremacy into seeming like a form of patriotism. Anti-communism with feminine characteristics.

Don't be shocked that it mostly worked. In the US, Republicans do it too. Where do you think all those white women voters talking about loving "America" and "family values" came from? This can be a very successful technique to turn targeted demographics under the right conditions. There may also be cultural reasons why it worked, but I won't speculate on those and do not want to overstate the culture factor.

The opposition groups that were quietly forming, which would later coalesce into the Tangwai, appear to have been mostly male. Additionally, they did not seem particularly concerned with the status of women -- at least not yet. In Chang's words:

Due to the male-dominated structure of Taiwan's democracy movement, the professed ideals of liberty, justice and equality did not necessarily translate into male activists' equal treatment of and respect for women activists.

(This is still kind of true, by the way.)

Okay, so what did the Tangwai have to offer women? Not much, at that point. Is it surprising that they didn't join en masse?

This is also why I don't think trying to tie women's political affiliations to "Taiwanese culture" is helpful: although the KMT could not exert perfect mind control, their distorting effect on Taiwan was so palpable and severe that it's very difficult to say how Taiwan would have evolved culturally without them.

The 1970s women's movements were liberal for their age, but conservative for ours

What The Feminine Mystique -- a deeply problematic book in some ways, but the cornerstone of second-wave feminism -- did for American feminism in the early 1960s, Annette Hsiu-lien Lu's New Feminism (新女性主義) did for Taiwan a decade later. She was not the only feminist of this era, but was indeed one of the founders of the that era's Taiwanese feminist movement, and her beliefs and the impact they made serve as an interesting case study.

Annette Lu from Wikimedia

While it was a turning point for Taiwan, certainly not all women would have boarded the women's rights train, even as Lu sought to equate women's rights with human rights. Movements take time, and this is no exception.

Martial Law was still very much in force, so it wasn't really any safer to start expressing feminist views than it had been for the past two decades. Lu herself was subject to surveillance, harassment and eventually arrest. After decades of being told to accept their place in a patriarchal society -- and having that order backed up with very real threats of harassment and violence -- 1970s Taiwanese feminism was never going to win the hearts and minds of all. No early movement does.

Some accuse Lu of simply appropriating Western-style feminism and importing it to Taiwan. This is not true, although her own brand of relational feminism crafted to suit Taiwanese society at the time was not without its problems.

Again, I quote at great length to get around barriers to academic work:

Although the substitution of “human rights” for “women’s rights” and contributions over entitlements might be regarded as a rhetorical strategy to make her “new feminism” compatible with the conservatism of Taiwan in the 1970s, Lü in fact had strong points of disagreement with American feminism as she had encountered it. First, Lü rejected the “sameness feminist” position that equality meant elimination of gender differences.

Supporting instead “difference feminism,” Lü argued that women should not strive to be like men, but should be “who they are.” In effect, she endorsed women's pursuit of higher education and professional careers while maintaining traditional gender roles within the family. Lü championed the image of the new woman who “holds a spatula with her left hand, and a pen with her right hand (左手拿鍋鏟,右手握筆桿)(Lü, 1977b,32; Lee, 2014,35). She furthermore advocated that talented women should show their femininity by using dress and makeup to cultivate a “soft” and “beautiful” appearance.

Finally, understanding that sexual liberation would be a flashpoint for resistance in Taiwan’s highly conservative society of the 1970s, Lü proclaimed that “new feminism” endorsed “love before marriage, marriage then sex” (Lü, 1977a, 152–154). Hence, Lü fought against institutional gender discrimination, while simultaneously upholding certain traditional standards of femininity, domesticity, female beauty, and chastity. Lü's relational feminism, as Chang writes,“suggested that one's individual freedom should be counterbalanced by fulfillment of specific obligations in family and in society”(Chang, 2009, 92).

Despite Lü's concerted efforts to make feminism compatible with aspects of Confucianism [ed: I'd say Neo-Confucianism], and to avoid challenging Taiwan's capitalist socio-political order, she drew fire from conservatives, and was soon subjected to political pressure and government surveillance. The martial law regime feared any political radicalism, and treated Lü's women's movement as a potential anti-government activity.

In other words, Lu -- who would go on to serve as Vice President under Chen Shui-bian -- was a "women can have it all" feminist. In favor of equal rights and opportunity, but still admonishing women to continue to perform traditional roles. Letting men off the hook from having to evolve their thinking, pushing a 'second shift' on women, and not holding any space for women to be "who they are", if they don't feel a traditional role fits them.

Her conservative views extend to love, marriage and sex, and generally, they don't seem to have changed very much in the intervening decades.

You may be wondering what her current views are. In 2003 (the same year that the Ministry of Justice proposed a human rights bill that would have legalized same-sex marriage, which didn't pass), although Lu was Vice President at the time and devoted a lot of time to human rights, she remarked that AIDS was "God's wrath" for homosexuality (she insists she was misinterpreted but has never offered a coherent explanation of what she claims to have meant).

Notably, some versions of that 2003 bill which included same-sex marriage credit Lu with the drafting. This source cites her as the convener of a related advisory group but does not mention same-sex marriage, and there's no evidence her commission was directly related to the bill. I don't know how this squares with her obviously homophobic comment in the same year, so all I can do is lay out the facts.

Now, 2003 might seem recent, but it was actually quite a long time ago in terms of the evolution of discourse and public belief around social issues. Has she evolved her thinking as well?

Not really.

More recently, she's tried to evade the issue by saying she "supports" LGBT people but that the courts were wrong to find a ban on same-sex marriage "unconstitutional", using some rather dubious logic. She went on to say that while she has no issue with it, society isn't ready for it, and the Tsai administration should focus on that rather than legalization. That equates to keeping it illegal, but with more steps. She also helped found the Formosa Alliance, which was pro-independence but opposed to marriage equality.

That sure sounds like someone trying to have it both ways: to oppose marriage equality without openly admitting it. Like someone trying to obstruct without looking like an obstructionist, trying to politic her way out of admitting she's not really an ally.

She also appears to be opposed to modern sex education, saying it will lead to an "overflow" of sex, which should instead "have dignity" (anyone familiar with, well, sex can affirm that it is many things, but "dignified" isn't really one of them. At least if it's good sex.)

All that said, Lu was one of the few early feminists who took a political position on the green-blue divide:

Inasmuch as the freedom to openly debate Taiwanese national identities was severely circumscribed under the martial-law regime of the Chinese Nationalist Party (i.e., Kuomintang or KMT), feminist activists strategically adopted a nonpartisan stance and refrained from discussion of this controversial topic (Chang, 2009: 160; Fan, 2000: 13–19, 26). Yun Fan posited that it was not until the era of democratisation in 1994 that most members of the Taipei Association for the Promotion of Women’s Rights (女權會, nüquanhui) explicitly voiced their support for Taiwan independence (Fan, 2000: 28–35). Hsiu-lien Lu (呂秀蓮, a.k.a. Annette Lu) was a notable exception to the political neutrality in Taiwan’s feminist community during the 1970s. As a citizen of Republic of China (ROC) on Taiwan, she advocated that Taiwan and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) should peacefully coexist as two ethnic Chinese states (H-l. Lu, 1979: 241).

What did that offer to the young women coming of age in the 1970s, and their mothers -- some of whom are still alive to vote? A choice between KMT-approved traditionalism, and a feminist ethos that, by attempting to render itself more palatable to Taiwanese society, became something that sounds more like conservatism today.

Certainly, some women simply chose to walk away from both models. Many, however, would have chosen a perspective that fit somewhere within what public discourse was offering.

The KMT finally began listening -- somewhat -- to feminist groups after the lifting of Martial Law in the mid-1980s, and granted some of their requests (the legalization of abortion happened around this time). While Annette Lu was in prison, Lee Yuan-chen and others formed a publishing house to keep the message of Taiwanese women's movements alive.

At the same time, while the DPP did have prominent female public figures (Chen Chu 陳菊 comes to mind), they weren't necessarily a beacon of women's equality.

Chen Chu, still in politics and one of my faves (WIkimedia)

The women's movement in general supported women voting across the political spectrum, and took pains to remain non-partisan. Of course, in that political climate, many of their adherents would have chosen the KMT. And chances are, they have simply stayed that way.

At the same time, their daughters and granddaughters have grown up decades later, after society had moved beyond Lu's "exhaust yourself trying to have it all" brand of feminism. More role models and more complex and varied discourse exists: there's simply more to choose from. It's no wonder that they don't seem anywhere near as interested in the same values.

Where does that leave us, in terms of women's support for various parties throughout Taiwanese history?

It's Wild Speculation Time

So, there are certainly women who support the KMT due to their background regardless of their views on women's rights, and the same for the DPP. Then a women's movement came along, aiming (mostly) to be non-political, which pushed the post-Martial Law KMT to be a little more amenable to women's rights, while the DPP was not necessarily a beacon of egalitarianism for women. If you put it that way, it seems clear why the women's movement didn't necessarily move the party identification needle for women.

Liberal women might therefore have voted for either party, not necessarily providing a large bump to the DPP. Some disaffected "radicals" (whose beliefs we'd see as pretty normal today) were certainly around, but not enough to make a difference.

And those "liberal women"? The 1970s-80s movements were liberal for their time, but not liberal as we'd define the word now. By today's standards, they are conservative.

And they likely hold the same views today as they did then.

Is it any surprise that Millennial women (and the Zoomers who can vote), who never experienced those decades and have known only democracy and more contemporary forms of liberalism, would almost certainly be different?

Men, of course, lived through all of this too. But men have a history of not being affected as much by women's movements. One of the principal questions women's rights activists face now is essentially 'he for she': how do you get men to change?

In other words, men chose their political parties without really having to think too much about what those parties were saying about their position in society. As the dominant group in a patriarchal culture, that place was assured by both major parties, so they could choose purely based on other ideologies they held.

Perhaps this allowed "liberalism" to take on a different meaning for men, as some came to embrace it: free to ignore the back-and-forth of the feminist cause, and free to simply 'not see' the misogyny that didn't affect them, they might come to a more DPP-friendly political sensibility through simply looking at the KMT's past and deciding to support the party that pushed for democratization, instead.

While I do think that older women trend far more conservative than younger women, and it's demonstrably true that Taiwanese women support the KMT at higher rates than men, I'm not sure this makes a case that women, as a whole, are more conservative than men. I would love to see a breakdown of the voting pattern of older vs. younger women, compared to that of older vs. younger men.

I bet you anything that the same trends we see in other countries holds true: political ideology tends to remain static, which is why older generations tend to be 'more conservative' as society liberalizes, but at the same time younger women are moving away from older ones ideologically. This may not show up in the data, however, perhaps because older women vote at higher rates, or because younger liberal women are more likely to turn to a smaller party instead of the DPP.

The party identification disparity is almost certainly not an artifact of the way the data was analyzed. It's highly unlikely to be due to factors such as longevity (women have a longer life expectancy than men, so there ought to be more very old women than very old men). According to Frozen Garlic, older men and women vote at about the same rate, but very old men vote at a higher rate than very old women.

I would be interested to see what happens with all of this in the next few years, as the KMT digs into the culture wars it's trying to manufacture. Will it push younger women to the DPP?

Anecdotally speaking, I do know at least one woman who hasn't tied her support of the KMT to conservative values. A thirtysomething, she supports marriage equality, and the LGBTQIA+ community as well. She has a career and aims to excel in it. She loves her family but doesn't necessarily feel the need for a 'traditional' life. Things like living with a boyfriend are not beyond the pale. I'd consider her a liberal, but she was also a die-hard supporter of Han Kuo-yu and reviles President Tsai.

I do not think she sees those things as remotely contradictory. She doesn't see the KMT as a socially conservative choice. Yet.

Targeted Marketing

This is my wildest speculation yet, so please don't expect academic rigor.

Think about the older female Taiwanese conservatives you know, or have seen on news shows talking about how Ma Ying-jeou is "handsome" or Han Kuo-yu is "charismatic".

No party in Taiwan has ever fielded a truly handsome man for president (Freddy Lim hasn't run...yet.) However, the KMT has a habit of fielding candidates appealing to older women, and I suspect this is intentional.

Ma Ying-jeou was once described to me as "my mom's idea of what a good 'catch' for a husband should be". Apparently, he once came across as refined, educated and upstanding. I understand that he was once conventionally "attractive" but honestly, I can't get past those cold, dead eyes.

Whereas Freddy...

There's really just no comparison, is there?

Ahem. Anyway. My friends mostly don't agree with this assessment of Ma as a 'catch'. But their mothers and aunts often do! Even boring Eric Chu could be seen as a suitably "good" fellow if a woman could not snag herself a Ma. I guess.

Another way of putting this: the men the KMT fields for top positions tend to remind some women of their husbands or fathers.

Suffice it to say, Chen Shui-bian, Frank Hsieh and Tsai Ing-wen had no chance of winning the "aunties think he's handsome" vote. Although Chen has a certain charisma, it doesn't come from his looks. He might remind some of their lively friend, but perhaps not their dad.

Tsai is an older woman herself, educated and refined. You'd think she'd attract those votes. But of course not: similar magnetic poles repel. She's everything their own mothers raised them not to be: single, childfree, leaning into her education and career. A woman like Tsai takes a look at the patriarchy and doesn't even bother to give it the finger before walking away and doing what she pleases.

The Ma dynamic seemed to play out with Han Kuo-yu. I think Han has a creepy look to him, personally. I don't know if the gambling, womanizing, temper and drinking rumors are true (well, we do know about some of it, seeing as he killed a guy and once beat up Chen Shui-bian.)

But, there is a certain charisma about him that I can see some women finding appealing. It's not quite toxic masculinity (just look at the shiba inu t-shirts) but it's in the same genus.

He even slightly resembles Chiang Kai-shek who, for all his faults, was not physically unattractive -- his repulsiveness was on the inside. (Click the link.)

Han looks like he's good at making friends in local businesses and down at the town rechao 熱炒 place. Like he'll buy his wife a string of high-rise luxury condos and a BMW if she doesn't ask too much about his sketchy business, or helps him run it. A real Lin Xigeng type.

A friend once described Han -- as with Ma -- as the kind of man your older relatives would advise you to marry.

To quote that friend -- after I gave her a look of utter horror -- "they think he's good looking, can be a provider and head of the family, and good at making money. They just expect husbands to cheat and gamble so they don't think that's important."

I cannot believe that most older Taiwanese women are influenced by this strategy, but the KMT wouldn't keep doing it if it didn't have some effect. Marketing is powerful. It's not an indictment of the target market when it works. They're even trying to export it to the "youth" with Wayne Chiang, despite the objective fact that the opposition has far more fanciable men.

Conclusions

There is so much I haven't explored here that I'd like to. Class surely plays a role, as it does in every other democracy. Is there a class divide in the voting behavior of Taiwanese women?

I have intentionally avoided too much discussion of "culture", because I don't think it's useful here. Culture is not static, and in any case, it's quite clear that how "Taiwanese culture" treats women has been deeply influenced, not only by the Japanese era (which allowed spaces for the modernization of women's spaces in some ways, but was deeply misogynist in others) but by the superimposition of the various pro-KMT "women's associations". What directions might Taiwanese culture have taken, if these colonizing influences had never imposed themselves on the country? I have no idea.

One area of culture I'd have liked to explore more is the way that traditional gender roles in Taiwan differ from the West, most notably (to me) in terms of accounting and financial responsibility. That women were entrusted not just with family budgets but often had a hand in running family businesses might offer insight into how the go-go-go capitalism of the Asian Tiger era affected women's views.

Women's support for smaller parties would also be an interesting area to look into. Is it the case, as in Korea, that liberal women are turning not to the DPP but to smaller parties? I'd like to know.

There is an entire contingent of families settled outside Taiwan, with Taiwanese heritage, where the older members are strong KMT supporters whereas their children and grandchildren may not be. Many of them can and do vote in Taiwan. They wouldn't have lived through the same things, and I have intentionally not discussed this group.

I have also stayed away from the most tempting argument: that a lot of older people were educated in a time when education was twisted to serve the KMT's goals and punish those who asked questions. First, although the Taiwanese education system has undergone reforms, I'm not sure it has changed enough. They're not making kids write about The Three Principles anymore, but neither are they really teaching critical thinking skills (which is not to say people don't develop them, just that they're not taught that in school). Second, because it would have affected women as well as men.

All I can say is this: women are not a monolith. Even in Taiwan, they are not a singular voting bloc.

However, the trends we see are indeed real. It's easy to ascribe them to "culture", or worse, "Confucianism", and offer a few generalities about gender norms in East Asian societies.

I think it's a lot more complicated than that, however, and has just as much to do with the history women of different generations lived through, and how they related to it.

I've talked mostly about older women here, and almost completely ignored Millennials and the Zoomers who can vote. This is because I don't think the same trends will hold for them, and the reasons why should be fairly obvious: pan-green politics in Taiwan is a lot more woman-friendly than it used to be (though there's still some way to go), the old KMT attempts at subjugating women have ended, and there's an overall turn away from the KMT by the youth.

It's impossible to wholly answer this question without doing dedicated research, which is not at all in my field. I hope, however, that this has provided a little historical insight into why women in general support the KMT at higher rates than men: that it's very likely a trend driven by older women rather than younger ones, and that there are likely large areas of overlap with social conservatism, but they're not exactly the same thing. That is, older women likely have their own reasons for supporting the DPP or KMT which may or may not align with their social views.

By the way, I've downloaded all the PDFs of the articles I've quoted here, so I'll be able to refer back to them when I lose institutional access. I am also fairly easy to find online. Email exists. Just saying.