Last summer, a student of mine asked me if, instead of regular class, we could walk around Dadaocheng as she'd never actually been. She's aware I go there often and know the area well. I met her at the Jiancheng traffic circle - this was before that glass circle building was torn down - and was genuinely surprised to learn that she didn't know three things:

- That the area was a swamp until Qing times

- That the circle itself had been a pond/reservoir as well as a bomb shelter, with the water from the pond used to put out fires from air raids, and after that was a popular culinary destination for local street food

- That the 228 Massacre began nearby, just to the west as one approaches the Nanjing-Yanping intersection.

After a quick backgrounder on Jiancheng Circle - which, again, I was truly surprised to be giving - we spent quite a bit of time ruminating at the plaque that marked where 228 began. It felt weird and slightly inappropriate to be a foreigner giving this information to a local, but here we were.

"Of course I know 228," she said. "But I didn't know where it happened. I guess I never thought about exactly where in the city it started."

We fell quiet.

"I already know this history," she repeated. "But maybe now I feel more connection to it, because I actually went to the spot."

After a quick backgrounder on Jiancheng Circle - which, again, I was truly surprised to be giving - we spent quite a bit of time ruminating at the plaque that marked where 228 began. It felt weird and slightly inappropriate to be a foreigner giving this information to a local, but here we were.

"Of course I know 228," she said. "But I didn't know where it happened. I guess I never thought about exactly where in the city it started."

We fell quiet.

|

| See that barely-noticeable granite plaque on the left? You'd miss it if you weren't looking for it. |

"I already know this history," she repeated. "But maybe now I feel more connection to it, because I actually went to the spot."

This is not to say she does not know her own country's history. By her own words, she does - quite probably as well as I know my American history. This will not be a hectoring "Taiwanese don't know their history!" post. I will never write such a post. If I ever approach that topic, it will be in a more realistic and nuanced way.

However, as we wandered around various other Dadaocheng landmarks - the old riverside mansions of major trading families, the municipal brothel, the old Yongle Market, Wang's Tea and more - she kept commenting, and I could feel, a deeper connection to her city being formed. We finished the day with her exclaiming again that she was genuinely surprised and regretful that she'd never taken the time to explore that neighborhood before. She seemed the most affected by the simple 228 commemorative plaque on that unexceptional stretch of sidewalk on Nanjing West Road.

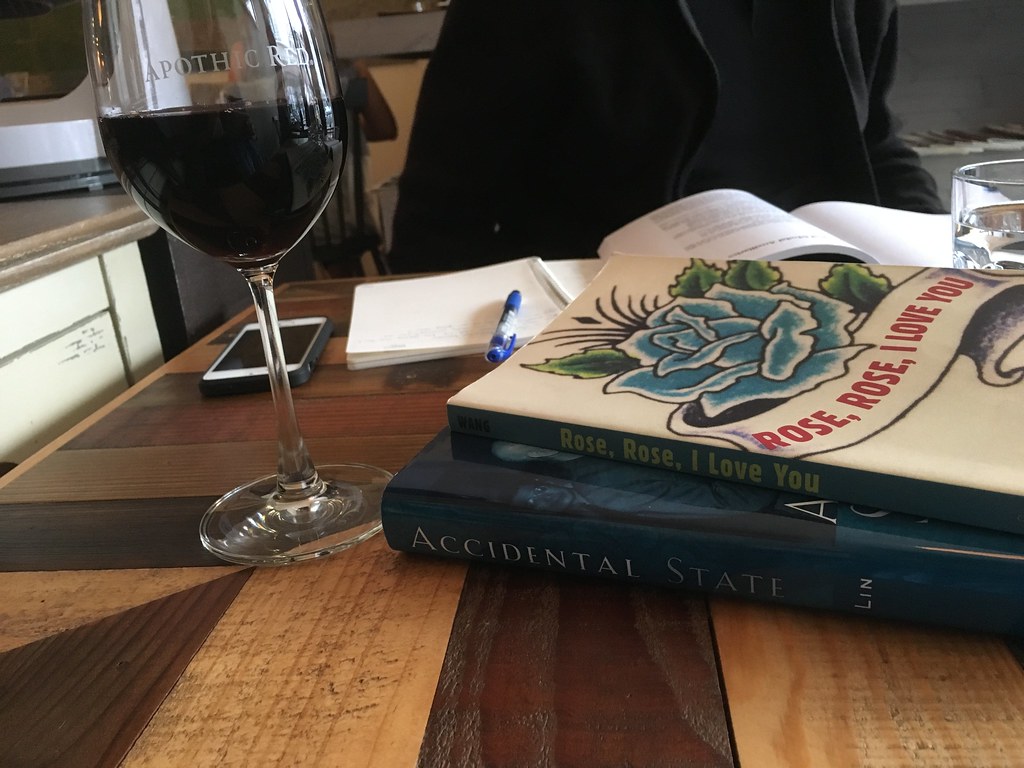

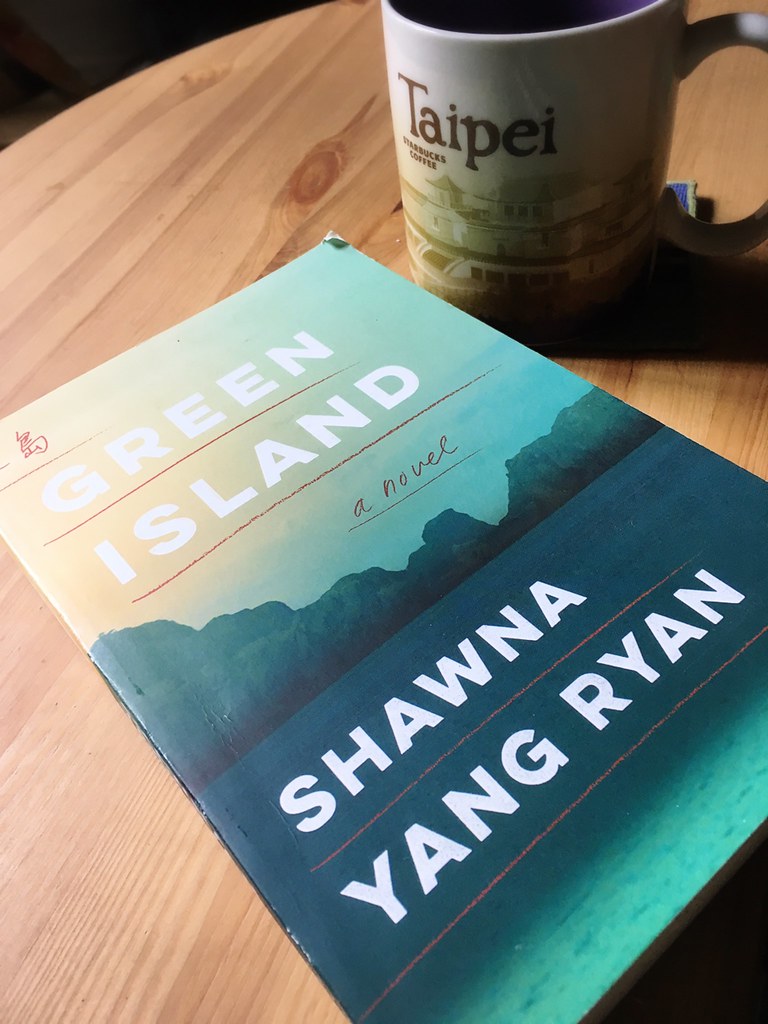

I've come back to this story because, as 228 approaches and as I plan to visit Nylon Cheng's office (the Cheng Nan-jung Liberty Museum) on that day (some people who want to go in our group are not free on the more appropriate date of April 7th), I have found it helpful to reflect on the importance of attaching knowledge of historical events to the more visceral feeling of visiting the places where they happened. Knowing the historical and emotional geography of your city, and even your country. Taiwan is an accidental state (as the shiny-brand-new book of the same name points out), and also accidentally in its current state. Knowing not just the facts and dates but also visiting the places where these things happened imparts an emotional connection to that history that reading a book or memorizing a list of dates can never do.

It is more fruitful, then, to reflect on how the 228 Massacre continues to affect Taiwan by connecting it to a real geographical point, a historical locus from which to better understand the city and country. This, not "history", is the connection I have noticed some acquaintances of mine lack. It's a problem not limited to Taiwan, but feels especially jarring here, where the Taiwanese identity movement is so closely tied to associations with history - many social activists think of themselves as carrying the torch of civil society from their predecessors - and the land itself. Cycling around Taiwan and climbing Jade Mountain are seen, if subconsciously, as activities that bring one closer to the land and identification with it, so it is confounding that so many loci of political and social history are unknown or forgotten. How many other Taipei residents know about 228 but haven't a clue where it happened?

Again, this is not to say nobody knows. I know many socially and politically active people who can and do visit these places regularly. I'm describing a trend I see among some friends and students; it is not meant to be an indictment of an entire society.

Of course, 228 is not the only site of historical interest that make up Taiwan's emotional geography. I could do a sweeping survey of the country and list many - from the (likely) beach in Manzhou where the events of the Mudan Incident began to the Wushe battlefield to Baguashan in Changhua to Guningtou Beach in Kinmen. Instead I'll just name a few that resonate with me in Taipei:

Qingshan Temple, which has an interesting backstory that very weirdly mirrors some of the stories told about shrines in In An Antique Land about an entirely different part of the world and, while not a great historical turning point, is a story that brings to life the temple culture of the waves of Hoklo immigration from China.

Students and friends: "Where is Qingshan Temple? I didn't know that story about Qingshan Wang!"

However, as we wandered around various other Dadaocheng landmarks - the old riverside mansions of major trading families, the municipal brothel, the old Yongle Market, Wang's Tea and more - she kept commenting, and I could feel, a deeper connection to her city being formed. We finished the day with her exclaiming again that she was genuinely surprised and regretful that she'd never taken the time to explore that neighborhood before. She seemed the most affected by the simple 228 commemorative plaque on that unexceptional stretch of sidewalk on Nanjing West Road.

I've come back to this story because, as 228 approaches and as I plan to visit Nylon Cheng's office (the Cheng Nan-jung Liberty Museum) on that day (some people who want to go in our group are not free on the more appropriate date of April 7th), I have found it helpful to reflect on the importance of attaching knowledge of historical events to the more visceral feeling of visiting the places where they happened. Knowing the historical and emotional geography of your city, and even your country. Taiwan is an accidental state (as the shiny-brand-new book of the same name points out), and also accidentally in its current state. Knowing not just the facts and dates but also visiting the places where these things happened imparts an emotional connection to that history that reading a book or memorizing a list of dates can never do.

It is more fruitful, then, to reflect on how the 228 Massacre continues to affect Taiwan by connecting it to a real geographical point, a historical locus from which to better understand the city and country. This, not "history", is the connection I have noticed some acquaintances of mine lack. It's a problem not limited to Taiwan, but feels especially jarring here, where the Taiwanese identity movement is so closely tied to associations with history - many social activists think of themselves as carrying the torch of civil society from their predecessors - and the land itself. Cycling around Taiwan and climbing Jade Mountain are seen, if subconsciously, as activities that bring one closer to the land and identification with it, so it is confounding that so many loci of political and social history are unknown or forgotten. How many other Taipei residents know about 228 but haven't a clue where it happened?

Again, this is not to say nobody knows. I know many socially and politically active people who can and do visit these places regularly. I'm describing a trend I see among some friends and students; it is not meant to be an indictment of an entire society.

Of course, 228 is not the only site of historical interest that make up Taiwan's emotional geography. I could do a sweeping survey of the country and list many - from the (likely) beach in Manzhou where the events of the Mudan Incident began to the Wushe battlefield to Baguashan in Changhua to Guningtou Beach in Kinmen. Instead I'll just name a few that resonate with me in Taipei:

Qingshan Temple, which has an interesting backstory that very weirdly mirrors some of the stories told about shrines in In An Antique Land about an entirely different part of the world and, while not a great historical turning point, is a story that brings to life the temple culture of the waves of Hoklo immigration from China.

Students and friends: "Where is Qingshan Temple? I didn't know that story about Qingshan Wang!"

Machangding Memorial Park, which gives me the heebiejeebies at night (though I wrote this post awhile ago, when I wasn't the writer or Taiwanophile that I am now, so please don't judge me too harshly for it)

Students and friends: "I've never been there - was it really an execution ground?" (Yes.)

Dihua Street - the old commercial center of Dadaocheng and subject of a well-known painting. Not for any major historical event but just the general sense of history (I'm particularly a fan of Xiahai temple and one house in particular, the one with the decorative ginseng around a high circular window. See if you can find it).

Students and friends: "What is there to do on Dihua Street?"

Students and friends: "What is there to do on Dihua Street?"

Ogon Shrine in Jinguashi (close enough to Taipei!) - simply because it's one of the easiest and only Japanese shrines that still has some existing structure that's within striking distance of Taipei. There is a much better-preserved temple in Taoyuan but the setting is not quite so evocative.

Students (not so much friends): There's a Japanese shrine ruin up there?

Students (not so much friends): There's a Japanese shrine ruin up there?

|

| Yes, there is. |

The Chung Nan-jung Liberty Museum, which I will admit I have not yet been to, mostly because that sort of thing tends to make me emotional, and I think deep down I've been avoiding it. However, it is crucial to understanding Taipei's emotional geography to know where Nylon Cheng immolated himself in his burning office and why, and to see the spot for yourself.

Students and friends: That's downtown? It's right near the MRT? I had no idea it was so close!

Chen Tian-lai's mansion - there is quite a bit of history here that you can read about in the link, but honestly, I've been known to head down there and just look at the facade. I'm a huge fan of 1920s colonial architecture. Very close to Dihua Street (I also like the Koo Mansion a bit to the north, down a lane you would never think to walk down, occupied currently by a kindergarten).

Students (but not friends, most of whom know this place): There's a mansion here?

The Wen-meng municipal brothel - no survey of women's history sites in Taiwan is complete without a stop here, although chances are all you'll get to see is the exterior.

Students and friends: Prostitution used to be legal? There was a government-run brothel? What?

Qingdao and Jinan Roads around the Legislative Yuan - frankly, if you weren't down here some evenings during the Sunflower occupation, you missed a seminal moment in Taiwanese history. I spent quite a bit of time here around this time three years ago, and the two streets are now synonymous in my visual memory with social movements in Taiwan.

Wistaria Tea House - first the home of the Japanese governor-general, the setting of Eat Drink Man Woman, and also a gathering place for political dissidents in the Dangwai era. Also, great tea.

OK, everyone knows this.

Students and friends: That's downtown? It's right near the MRT? I had no idea it was so close!

Chen Tian-lai's mansion - there is quite a bit of history here that you can read about in the link, but honestly, I've been known to head down there and just look at the facade. I'm a huge fan of 1920s colonial architecture. Very close to Dihua Street (I also like the Koo Mansion a bit to the north, down a lane you would never think to walk down, occupied currently by a kindergarten).

Students (but not friends, most of whom know this place): There's a mansion here?

The Wen-meng municipal brothel - no survey of women's history sites in Taiwan is complete without a stop here, although chances are all you'll get to see is the exterior.

Students and friends: Prostitution used to be legal? There was a government-run brothel? What?

Qingdao and Jinan Roads around the Legislative Yuan - frankly, if you weren't down here some evenings during the Sunflower occupation, you missed a seminal moment in Taiwanese history. I spent quite a bit of time here around this time three years ago, and the two streets are now synonymous in my visual memory with social movements in Taiwan.

Wistaria Tea House - first the home of the Japanese governor-general, the setting of Eat Drink Man Woman, and also a gathering place for political dissidents in the Dangwai era. Also, great tea.

OK, everyone knows this.

These are just a few of the many possible choices, and I narrowed it down by choosing those that matter to me - the ones that have made the history of Taipei and of Taiwan come alive for me (and in one case, really come alive, as I was there in the crowd when things went down).

In any case, I encourage you to leave your homes this long weekend commemorating one of Taiwan's greatest tragedies and saddest cultural touchstones and go out and see some things for yourself. I promise, you'll connect with the city on a more physical level. Go!

In any case, I encourage you to leave your homes this long weekend commemorating one of Taiwan's greatest tragedies and saddest cultural touchstones and go out and see some things for yourself. I promise, you'll connect with the city on a more physical level. Go!