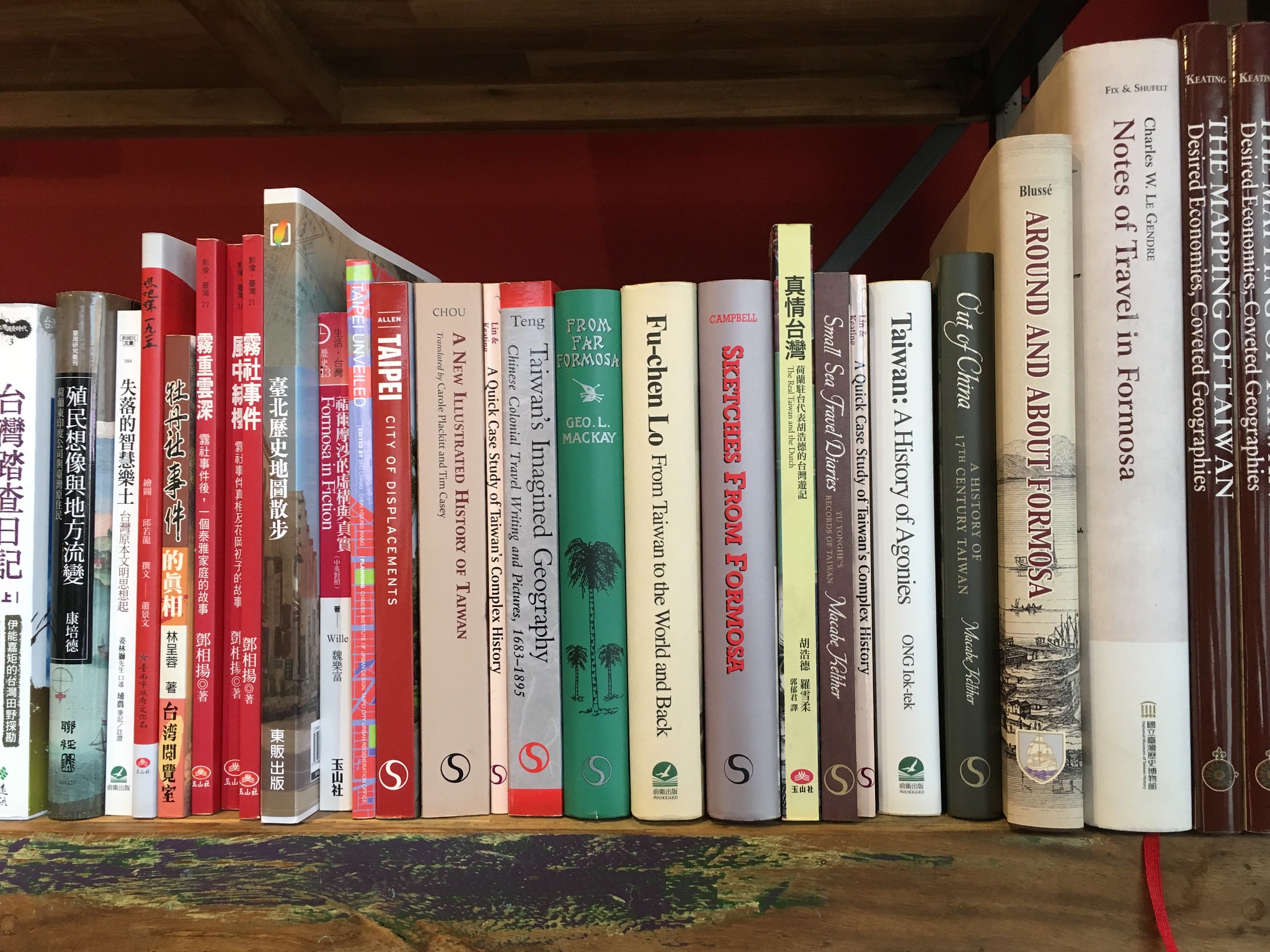

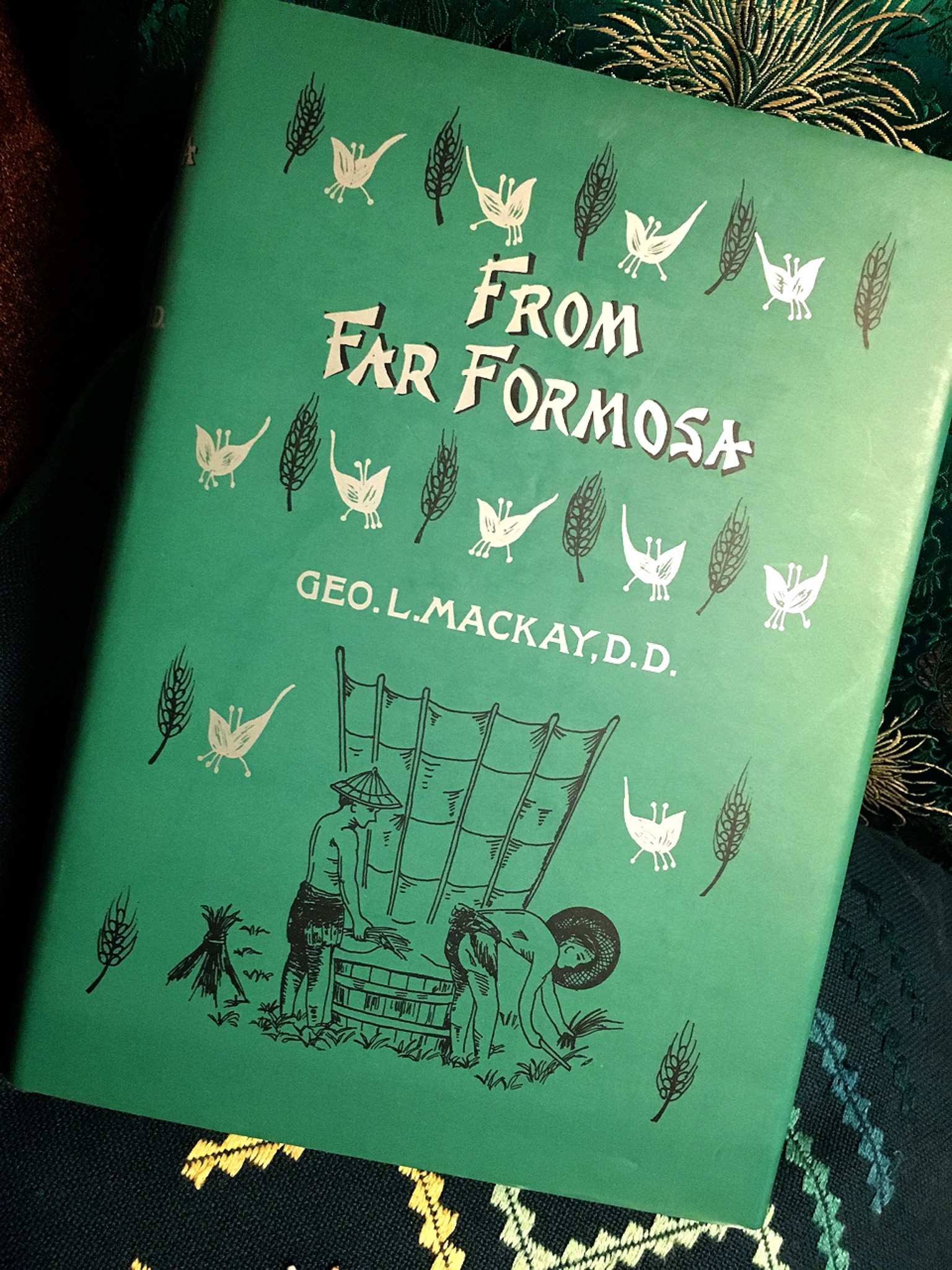

Loyal readers of Lao Ren Cha might think it impossible that I would have had the time to read From Far Formosa while I've been working on my final paper for my first term at Exeter. These astute fans are correct! However, I would like to share a few impressions of George Mackay's classic of writings about Taiwan, in which he describes life, people and missionary work in Taiwan from his experience living there for over twenty years. First published in 1896, it is one of the most fascinating accounts of what life was like in Formosa at the very end of Qing colonial rule in Taiwan, and my 2002 SMC edition includes a number of interesting photographs and maps. Unfortunately, the pleasure of reading it is somewhat hampered by Mackay's failure to mention the most pivotal Taiwanese cultural institution of his - and our - time.

That said, From Far Formosa is a brilliant read - I was especially struck by the way Mackay describes his "first views of Formosa" and how they were later echoed by Janet Montgomery McGovern in Among The Headhunters of Formosa about two decades later, when the island was firmly under Japanese control. Mackay writes:

Beautiful indeed was that first view of North Formosa, as seen from the deck of the steamer in the harbor at Tamsui. We all stood and gazed, deeply impressed. In the evening we wandered out over the broad table-land and the downs toward the sea. The fine large fir-trees, not found near Ta-kow, attracted Richie's eye and reminded him of his Scottish home. But when he saw the situation of Tamsui, standing over against a solitary mountain peak that rose seventeen hundred feet, and backed on the east and south by range after range climbing two thousand, three thousand, and four thousand feet high, his soul was stirred to its depth, and sweeping the horizon with his hand he exclaimed:

"Mackay, this is your parish."

A stirring way to introduce Taiwan - anyone who has come to understand why this is called Ilha Formosa (the beautiful island) will understand how that moment must have felt. This is why it's befuddling that this heartfelt rendering of the first views doesn't include his first impression of what must have been a visceral, soul-illuminating experience. What I'm trying to say is - how could Mackay not have written about the toilet restaurant in From Far Formosa? What could be his motivations for such a glaring error?

In fact, how can anyone claim to have visited Taiwan if they never went to the toilet restaurant?

So, while I enjoyed the book, this was the one thing I just couldn't shake - how is it that Mackay catalogued everything he had learned about Taiwan in such meticulous and loving detail, and yet never once mentioned the most distinctive feature on the island, the one thing any visitor to Taiwan would immediately become aware of and be drawn to? The one thing that wave after wave of foreigners who once came to Taiwan by boat and now arrive by plane have been compelled to write about?

Was his omission deliberate, perhaps a consideration brought about by his religious faith? I considered this as I read on, not believing that he'd leave such a crucial facet of traditional Formosan culture out of his masterwork. That didn't make a lot of sense, though: as far as I'm aware, Christians have massive and inexplicable hangups about sex, gender and sexual orientation, but aren't particularly bothered by bowel movements. What about a toilet restaurant might be such a taboo for them - after all, surely even Jesus relieved himself in the usual way (though perhaps not in a Modern Toilet as we envision them). However, although I was raised Christian, I was never particularly interested in it as a belief system or philosophy, and as such don't know much about it beyond some core beliefs of the church I was raised in. Scripture and catechism and all other matters ecumenical are not my purview - perhaps someone better-versed in these areas can weigh on in the late 19th century view of Mackay's particular strain of Christian faith on this matter.

What is further confounding is that Mackay declines to mention the toilet restaurant when talking about both Formosans of Chinese and indigenous descent (this is true across all tribes discussed in the book). When it comes to Chinese, he neglects entirely to discuss the careful placement of toilet bowl seats according to the ancient precepts of feng shui, or to compare Taiwanese toilet-restaurant seating feng shui to its slightly different accepted interpretation in China at the time - in China, toilet seats made of plastic with embedded glitter were typically placed facing the till, in order to facilitate the flow of money according to the movement of qi around the restaurant. In Taiwanese feng shui, rules about glitter or non-glitter plastic toilet seat covers are not stressed as much, but the north-south placement of miniature squat-toilet bowls filled with spirals of chocolate ice cream when served to customers is of the utmost importance. After more than twenty years in Taiwan, surely Mackay - who observed religious customs closely - noticed this small but important difference.

Mackay's toilet-restaurant-related blind spots are no better when discussing his travels among the indigenous. One memorable passage, he describes a trek into the mountains with a group of "savages" (in a chapter titled "Savage Life and Customs"), writing:

Higher and higher we wound and cut and climbed. Far up we reached a little open space among the tangle, and could see that the next day would take us to the topmost peak. Below could be seen all the ranges, with their intervening valleys, All around was the wild luxuriance of cypress and camphor, orange, plum and apple, chestnut, oak and palm, while the umbrella-like tree fern rose majestically some thirty feet high, with its spreading fronds fully twenty feet long.

After such a luxurious description of wild mountain nature in late 19th-century Taiwan, how was Mackay not immediately inspired to compare the natural wonders around him with the man-made wonders of the toilet restaurant? The two bring to mind a dichotomy of images so similar that it is difficult to comprehend how an astute observer such as Mackay would not have made the connection. He continues, describing the trek being unexpectedly pinched off before it was completed:

But after that night of ecstasy came the morning of disappointment. With the snow-capped heights of Sylvia almost within reach, the chief announced his decision to return to the "Huts." He had been out interviewing the birds, and their flight warned him back. There was nothing for it but to fall into line and retrace our steps. Reluctantly, bit with much more rapidity, the descent was made, and we arrived at the village in time for the braves to participate in the devilish jubilation over a head brought in during our absence. One ugly old chief, wild with the excitement of the dance, put his arm around my neck and pressed me to drink with him from his bamboo, mouth to mouth. I refused, stepped back, looked him sternly square in the face, and he was cowed and made apologies. When we left then they were urgent in their invitations to their "black-bearded kinsman" to visit them again.

While I find it a bit unsettling that Mackay was so openly rude to a tribal elder - intoxicated or not - I am even more flummoxed by his complete failure to mention the importance to indigenous Formosan societies of the toilet restaurant. A traditional sharing from the urinal-shaped glass out of which Taiwan Beer is sold can help make amends for any social gaffes that occur, and Mackay and the chief might have entertained themselves more amicable in this fashion. (A portable urine container also filled with Taiwan Beer is a second acceptable option among most indigenous tribes, but not all - a visitor to these areas is well-advised to note the differences in local customs.)

All in all, From Far Formosa is an interesting read and valuable time capsule. However, it doesn't escape the flaws of other books about specific periods in Taiwanese history in its baffling omission of the toilet restaurant as central to Taiwanese culture. Some observant writers are wise to include this critical cultural touchstone: in Lost Colony, Tonio Andrade, for example, is wise to include the importance of the toilet restaurant in the series of events that led to Koxinga's taking Taiwan from the Dutch, and George H. Kerr notably discusses the pivotal role the toilet restaurant played at length when describing the horrors of the aftermath of the 228 Incident in Formosa Betrayed. Manthorpe only includes six paragraphs on the toilet restaurant in Forbidden Nation, but his brevity on the subject can be forgiven, considering the sheer amount of Taiwanese history he covers. From Far Formosa, too, would have benefited from the understanding of the key cultural role of the toilet restaurant in Taiwanese history and modern political economy that these other writers have displayed.