This is a good time to announce that Brendan and I have been slowly working through a project: we’ve each been reading a selection of the various history books on Taiwan with an eye to creating a collaborative post discussing all of them, both on their own merits and in relation to each other. Look for that to be coming out sooner than you’d think.

This is a good time to announce that Brendan and I have been slowly working through a project: we’ve each been reading a selection of the various history books on Taiwan with an eye to creating a collaborative post discussing all of them, both on their own merits and in relation to each other. Look for that to be coming out sooner than you’d think.

In the meantime, here’s a review of one of the seminal texts in general Taiwan history: Jonathan Manthorpe’s Forbidden Nation.

When you open this book, two things are immediately apparent: first, that Forbidden Nation is not quite chronological. Rather, it frames the middle chapters with the saga of Chen Shui-bian’s re-election in 2004. It opens with Two Shots on Jinhua Road, which tells the story of Chen’s attempted assassination while campaigning with a flair that some might find overly dramatic, but which does engage the reader. The text then re-sets to pre-colonial Taiwan, working its way through the Dutch, Koxinga, the Qing, the Republic of Formosa, the Japanese, the KMT dictatorship and democratization, ending once again with Chen.

Second, while parts of the narrative do a good job of looking at an issue from multiple perspectives, others read like a straight op-ed. Manthorpe is unapologetically pro-Taiwan and pro-independence, to the point that the very first sentence of the preface reads: "Taiwan is entering an era when the four-hundred-year-old dream of the islands 23 million people to be internationally recognized as sovereign masters of their own house will be won or lost."

I’m willing to accept this, but not because his editorial line reflects my own. Rather, after considering multiple factors, he comes to consistently pro-Taiwan conclusions that I agree are the most accurate depiction of reality. In what ways did the KMT screw up — you’ll be shocked to learn that it was most of them — and where were they successful? Was the Republic of Formosa an expression of Taiwanese identity or not? Did the Japanese treat Taiwan well or not?

I don’t always agree with him; for example, I’m not sure that their land reform program was as unambiguously successful as he depicts it. But doesn’t give false neutrality or weak-kneed both-sidesism even a single second, and I appreciate that.

Indeed, in the years since Forbidden Nation was published, Manthorpe was proven to be right. Sovereignty is indeed the greatest dream of Taiwan and now we have the numbers to prove it.

However, it’s far from a perfect text. Brendan noted in his review that the narrative centers non-Taiwanese: you learn more about Robert Swinhoe than Nylon Deng, who doesn’t appear at all. More about Koxinga than Lee Teng-hui (although Lee does get fairly in-depth treatment). More about Soong Mei-ling than Annette Lu. Chen Chu, as far as I remember, is absent completely whereas KMTers, mostly from China, get plenty of attention. There is a lot of discussion of how rebellions were put down, but not much on why the rebellions happened or the internal mechanics of the more notable ones.

All in all, the narrative is more about the colonizers than the colonized, as though Taiwan is a place that has things done to it (which is indeed part of the historical narrative) and far less a nation that Taiwanese themselves built. Some threads aren’t carried through clearly; your average neophyte reader would never make the connection that Chen Shui-bian had ties to the Kaohsiung Incident, for example. I haven’t done a deeper textual analysis to find actual numbers, but there also aren’t many women mentioned, despite the ways that the women’s rights movement in Taiwan has converged and diverged with the Tangwai and Taiwan independence activism. There’s discussion of how long Taiwanese identity and the home-rule, democracy and independence movements have existed, but nothing on their internal mechanics. The White Lilies are erased entirely.

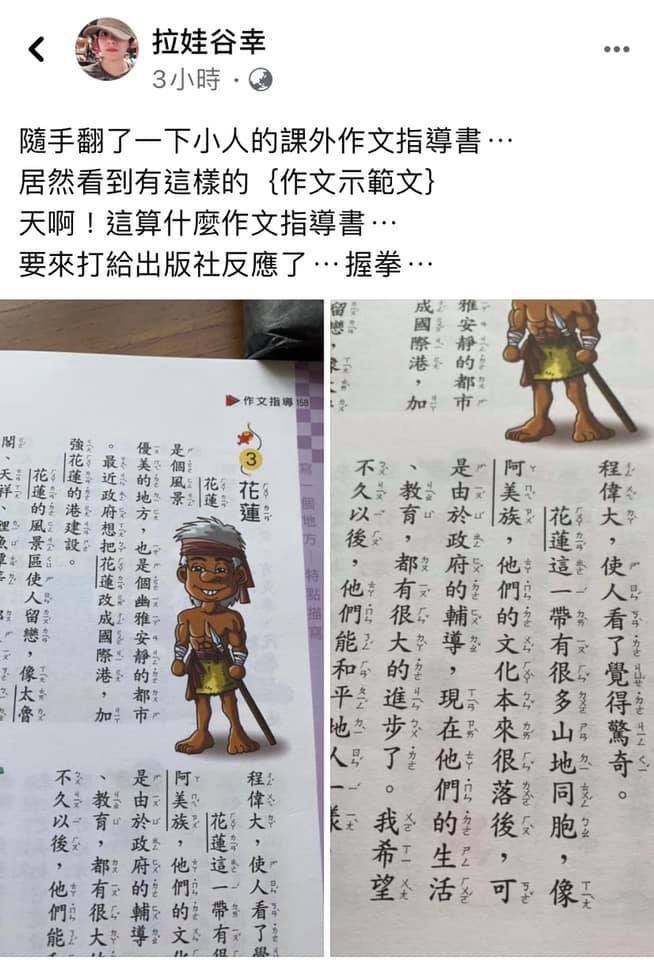

The narrative is also very much a “Great Men” view of history. You get a lot of movers, shakers and leaders — most of them not Taiwanese — but no clear sense of how all of this affected everyday people, or how they lived. Indigenous Taiwan is especially short-changed: Manthorpe spends roughly 20 pages on pre-colonial Taiwan, not entirely focused on Indigenous people. Some of the chapter titles are questionable (I think Barbarian Territory is meant to be ironic, and I'm not sure what I think of Pirate Haven), and much of this section focuses on how outsiders -- more Great Men -- viewed Taiwan rather than what life was like here centuries ago. Manthorpe doesn't meaningfully engage with Indigenous perspectives later in the narrative, either.

This is both more than a lot of writers do and less than is necessary. 400 Years of Taiwan History and Taiwan: A Political History gloss over this period as quickly as possible, with the former stating provably incorrect points, such as the idea that struggling Hoklo and Indigenous worked together to fight the elites (nope). A History of Agonies is openly offensive toward Indigenous Taiwanese. A New Illustrated History of Taiwan offers a bit more, covering pre-Dutch Taiwan in about 50 pages. And yet a huge chunk of Forbidden Nation (about 50 pages out of that 250) is dedicated to Koxinga and his descendants. While interesting, I don’t think it merits cutting more modern and possibly more relevant figures from the narrative.

Despite these imperfections, Forbidden Nation does get some things right. Unlike some of the aforementioned texts, which are interesting in situ for the insight they share on a certain kind of outdated pro-independence thought process, Forbidden Nation can be recommended as something closer to a straight history, if that can be said of any text. It’s fairly short — about 250 pages, a length that isn’t too intimidating for anyone first approaching Taiwanese history. Both Taiwan: A New History and A New Illustrated History of Taiwan is that it’s fairly long, and that can be intimidating. The writing style is reasonably engaging, which elevates it above A Political History and A New History, both of which are fairly dry.

It also hits a lot of the right “beats” — the crucial turning points and notions from Taiwan’s history that underpin its identity. If you want a newcomer to understand a few basic things about Taiwanese history which explain why and how Taiwan became what it is today, this book will provide that. A lot of the arguments those who advocate for Taiwan keep rehashing to people who have opinions not in line with robust historical interpretation (that’s a fancy way to say “anti-Taiwan trolls whose opinions are wrong”) originate in Manthorpe’s text.

Let’s take a look at some of those “beats”. If I could create a bullet list of things I want people beginning to learn about Taiwan to understand, it would look roughly like this:

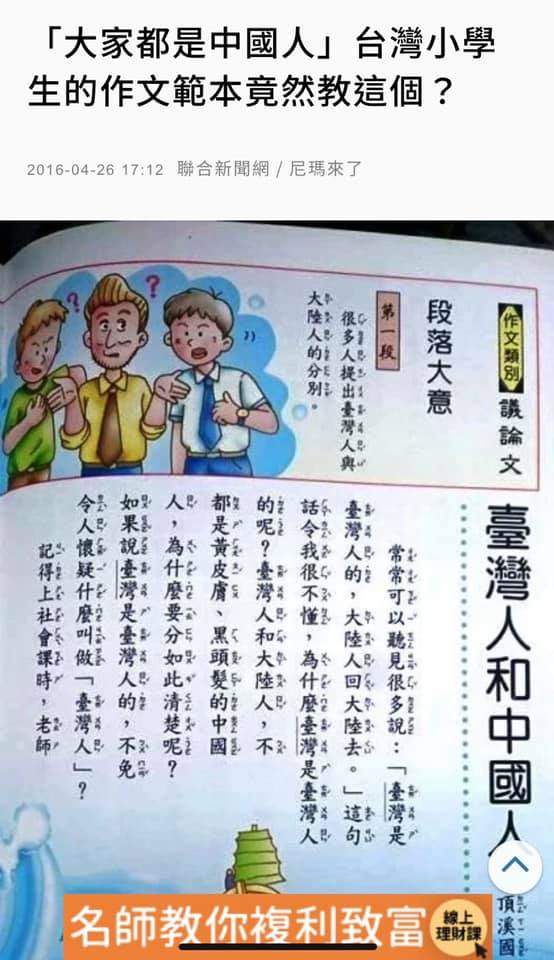

1.) China’s claim to Taiwan as an inalienable part of its territory “since antiquity” is entirely false; they cared not at all for it and didn’t even want to keep it initially.

2.) There is a strong argument for considering Qing control of Taiwan to be colonial. Labeling all rulers of Taiwan except those that come from China as “colonizers” but China as somehow not that plays into the ruse that Taiwan is essentially Chinese.

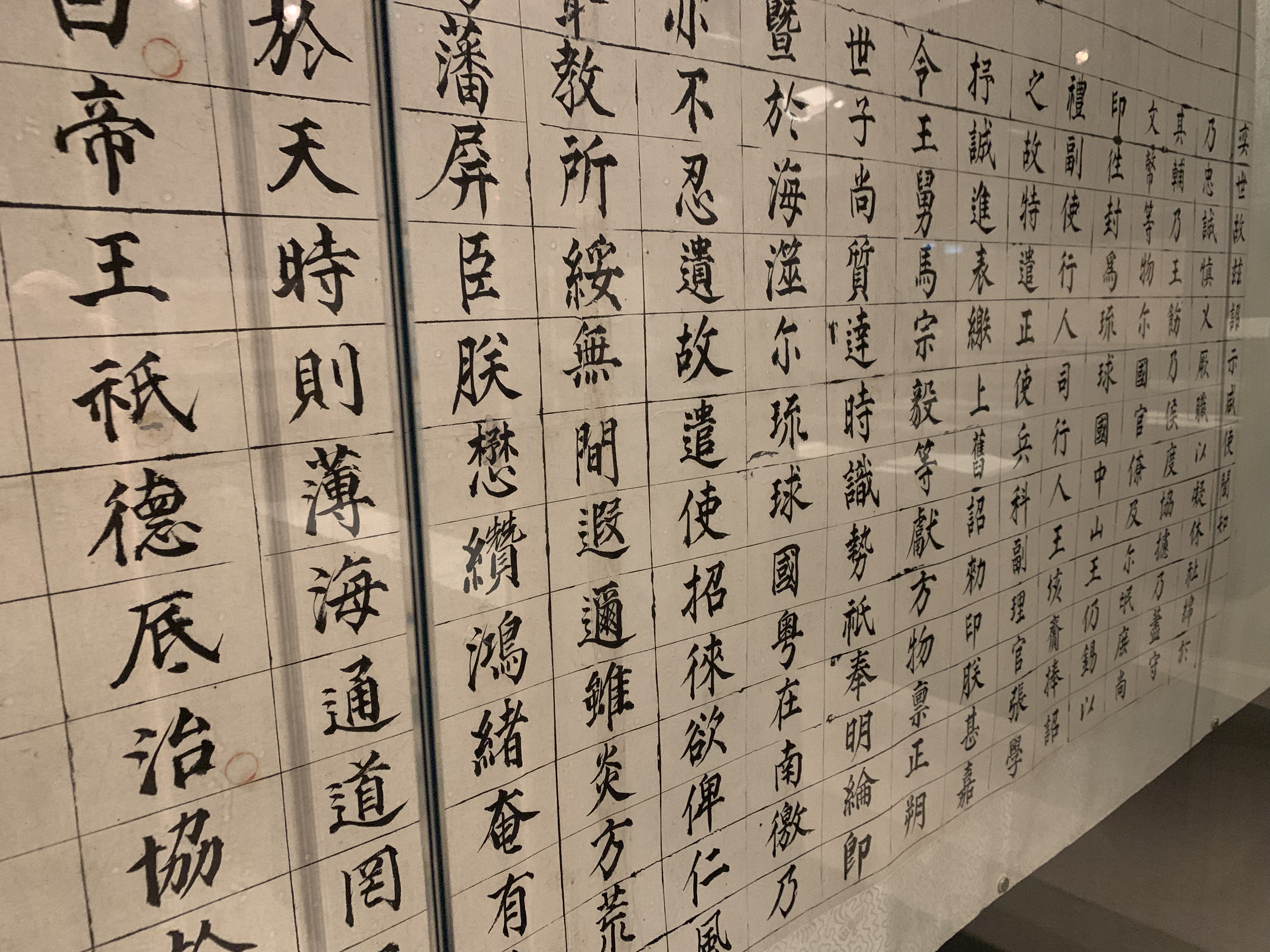

3.) The Qing didn’t control all of Taiwan for most of their time here, and certainly didn’t do much to develop it.

4.) The 1895 Republic was a flawed endeavor at best, and not a clear expression of early pro-independence sentiment. However, the rebellions that took place throughout Qing rule indicate that Taiwanese identity and the desire for sovereignty had at least some pre-1947 roots.

5.) The Japanese colonial era was not a halcyon era. It’s everything that came after it that causes older people to look back with nostalgia - how awful did the KMT have to be that Taiwanese would look back on the way Japan treated them and see that it was comparatively better?

6.) Taiwan was comparatively developed before the KMT showed up, and a lot of the “development” the KMT engaged in was really just cleaning up a mess they themselves made.

7.) Chiang Kai-shek absolutely knew about 228 and was perfectly aware that his underlings were committing a massacre. He approved of it.

8.) There were other post-war options for Taiwan; being absorbed by the ROC was rendered likely by the non-binding Cairo Declaration but not inevitable.

9.) If you actually look at the series of treaties, communiques, assurances etc. both post-war and as the US was switching diplomatic recognition, you’ll see that there’s no basis to claim that Taiwan is legally a part of some inevitable “one China”.

10.) Taiwan was built by Taiwanese. However, if you want to credit outside assistance (the KMT counts as “outside”), then US protection (due to Korean War-related strategic interests) and US aid did more for Taiwan than anyone else.

11.) Taiwan’s path to democracy was painful. They’re not going to give it up and change such a fundamental aspect of their culture just because China wishes it so. It is quite simply never going to happen. (Manthorpe doesn’t say this explicitly but that’s what his narrative builds to).

12.) And yes, the KMT can also be considered a colonial power in Taiwan. They have treated this country and its identity as just as disposable as the Qing.

...and that’s the thing. Forbidden Nation touches on all of this. It gives you what you need to understand that Taiwanese independence is not a radical notion, it’s a natural outgrowth of the country’s own history. It allows readers to realize that instead of asking how Taiwan could possibly avoid unification with China, we should be asking how it could ever possibly unify peacefully. It’s quite clear that it simply cannot, and will not.

My final thought: Forbidden Nation is not for people who already have a deep knowledge of Taiwanese history. I learned a few new things, but generally speaking I knew all of the skeins of historical trends and events that, when uncoiled to their full length and woven together, create a picture of Taiwan which simply can’t be denied. If anything, I would have preferred if the parts covering modern Taiwanese history were fleshed out more, with notable local activists and marginalized groups (including women) given more space in the story.

However, if a newcomer to Taiwan or someone interested in learning more about this country asks for a book recommendation, this will give them the fundamentals and will help defeat those “but isn’t the culture Chinese?” questions before they come up. Because I’m not a fan of the lens through which it tells Taiwan’s story — it can’t all be about Notable Men who usually aren’t Taiwanese! — I’d recommend that potential readers start with Forbidden Nation, but pick up A New Illustrated History of Taiwan afterwards. One for the historical “beats”, and the other to hear all the voices Manthorpe left out and get a clearer idea of what life was actually like in Taiwan throughout history.