As you approach the Museum of Archaeology in Tainan Science Park, you might not notice its dark exterior of stacked bricks. This unassumingly natural edifice almost seems to rise out of the grasses, bushes and flowers around it, as though they are part of it and it of them. Even the paved areas have different textures of stone, with the main entrance at the end of a long outdoor passage that cuts open at various intervals, as though giving you a glimpse of the world here, and here, and there. Throughout the exterior, more modern elements in metal and glass bring the building into the future.

The easy symbolism here is "melding the ancient and modern", but I think that's too simplistic. The dark, low stacked stone of the exterior recalls Rukai Indigenous stacked-slate housebuilding techniques. The cuts in the entrance hall remind you that we only view moments in history as a cutting-in, and must use our imaginations to fill in the details.

Once inside, natural wood benches and a large atrium allow families to keep children occupied while someone stands in line for tickets. As you ascend the escalators, an interior side of the facade comes into view: the Rukai slate-house colors are still there, but now they're designed as geological layers, complete with replica fossils that come into view as you rise.

The Archaeology Museum took quite awhile to build, having been first conceived when priceless finds were discovered when developing the science park, from Indigenous settlements dating back thousands of years. (There are some shards of modern pottery and even "figurines of foreigners" from the Dutch era, too).

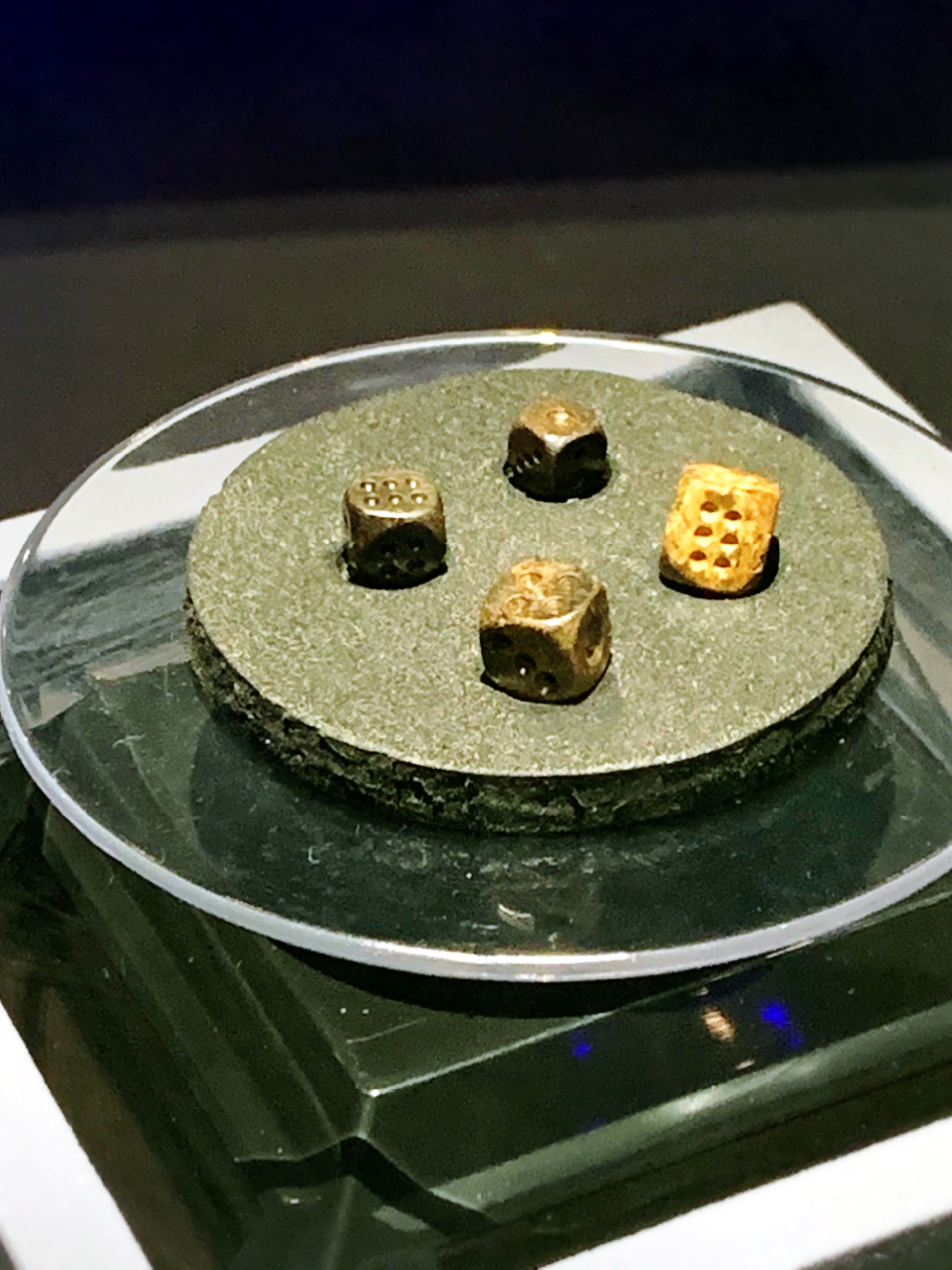

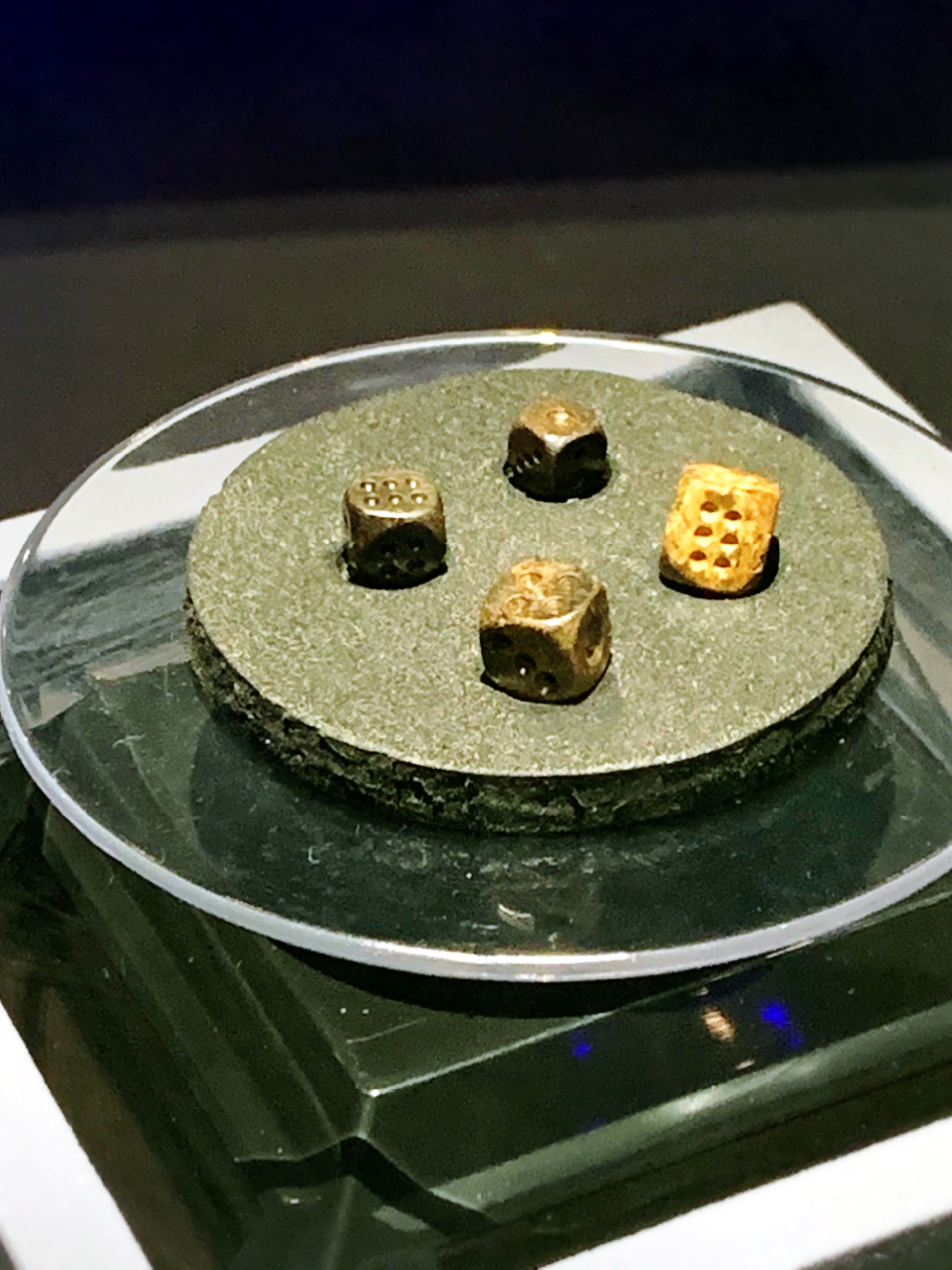

Tainan has built on its reputation as a historical and cultural capital with its Taiwan-focused museums: the Tainan Fine Art Museum, housed in two buildings, one vintage and one modern; the National Museum of Taiwan History which offers a bracing definition of "who is Taiwanese" alongside a building-size timeline of the country's history with (mostly replica) artifacts; and the Museum of Archaeology, understated and elegant, displaying the real deal -- including treasures like a carved deer antler knife handle, centuries-old dice, and millenia-old pottery, tools and jewelry.

There is more to love about this museum, despite its distance from the city center -- there's probably a bus, but I recommend a car to get there. We went with a local friend. But first, I want to talk about a particular effect it had on me.

It's no secret that I'm not a big fan of the National Palace Museum. Sometimes when subjugationists sneer that if Taiwan wants to be independent so much, why doesn't it just give back all the treasures they carted over from China?

I usually retort: "Sure, you can have your junk back. Guaranteed freedom matter more."

I don't really mean this -- well, I would be in favor of sending most of it back across the strait, but I don't get a say. Regardless, that was never a serious proposition. Rather, I know perfectly well that it's not "junk". It's a museum in an ugly building full of priceless foreign artifacts, displayed in the most unengaging manner possible -- bland rooms of vases and scrolls, with very little context offered to tell you why each one matters in its own way. You are supposed to gape at it and agree that it matters, without getting a real feel for anything. (Some items, like the carved ivory or the colorful porcelains of the Empress Dowager Cixi do indeed stand out on their own).

I tell visitors that it's worth going if you are specifically interested in Chinese history, but you won't learn much about Taiwan beyond a better understanding of all the loot the retreating ROC hauled over here.

Otherwise, though, it's just kind of there, in its ugly building, expecting your admiration and thinking it owes you not one jot of engagement that you don't bring to the visit yourself. A shrine to a foreign country, a lost war, an enforced identity that couldn't even be enforced very well once Taiwanese people were actually given a say.

In other words, it's easy to take a big ol' dump on the National Palace Museum. Criticism is easy. "This thing sucks!" "I don't like that!" "Most. Uninsightful. Song-Ming Blue and White Porcelain Display. Ever!" I could do that all day.

What's harder is offering a positive alternative: try this place instead. This is cool. This is a hidden gem. This truly captures a tiny piece of the soul of Taiwan. This other museum is small but really captures a poignant moment of Taiwanese history.

The Tainan and Taipei Fine Arts Museums are just such museums. Do not miss the exhibit of vintage Taiwanese paintings from the Japanese era, including the original Dihua Street market scene by Kuo Hseuh-hu (郭雪湖), ending in two weeks. The Taipei Museum of Contemporary Art too, but recent scandals have soured me on it a tad. The Shunye Museum of Formosan Aborigines is across the street from the National Palace Museum and is a more edifying visit if you are actually interested in Taiwan. The Nylon Deng Memorial Museum deserves to be in this list, though it's difficult to access in English. The 228 Museum, the National Prehistory Museum (temporarily closed for renovation), Jingmei Human Rights Museum and Green Island's White Terror Memorial Park and so many more -- too many, in fact, to list -- not only offer deeper, more intimate and more local understandings of Taiwan.

And that's just the short list.

All of these museums utilize design concepts to offer engaging museums with experiences beyond we built this Chinese-lookin' cement thing and put all our stuff in it, people will come because of its obviously superior cultural refinement. Even the museums that were once prisons have options to discuss what you are seeing with a former inmate who'd been imprisoned there.

But again, it's easy to criticize that old dinosaur up in Shilin.

Instead, let the design elements of places like the Tainan Museum of Archaeology wash over you and perhaps spur you to think a little more deeply about the subtler elements.

Coming here helped me remember: it's easy to criticize. It's easy to say the National Palace Museum pushes a (mostly fabricated) narrative of Chinese history "preserved" by "free China" in Taiwan.

It's difficult to offer a positive alternative. It's even harder to offer that alternative simply, for its own sake, without a specific agenda. Or rather, if there is an agenda, it's simply to get more people to go to museums about Taiwan when they visit Taiwan.

There's a lot to like about the place: when you enter, one of the first things you come across is a timeline of who exactly lived in this part of Tainan when.

Ya think the vast majority of Taiwanese history is Han? Think again, mofos:

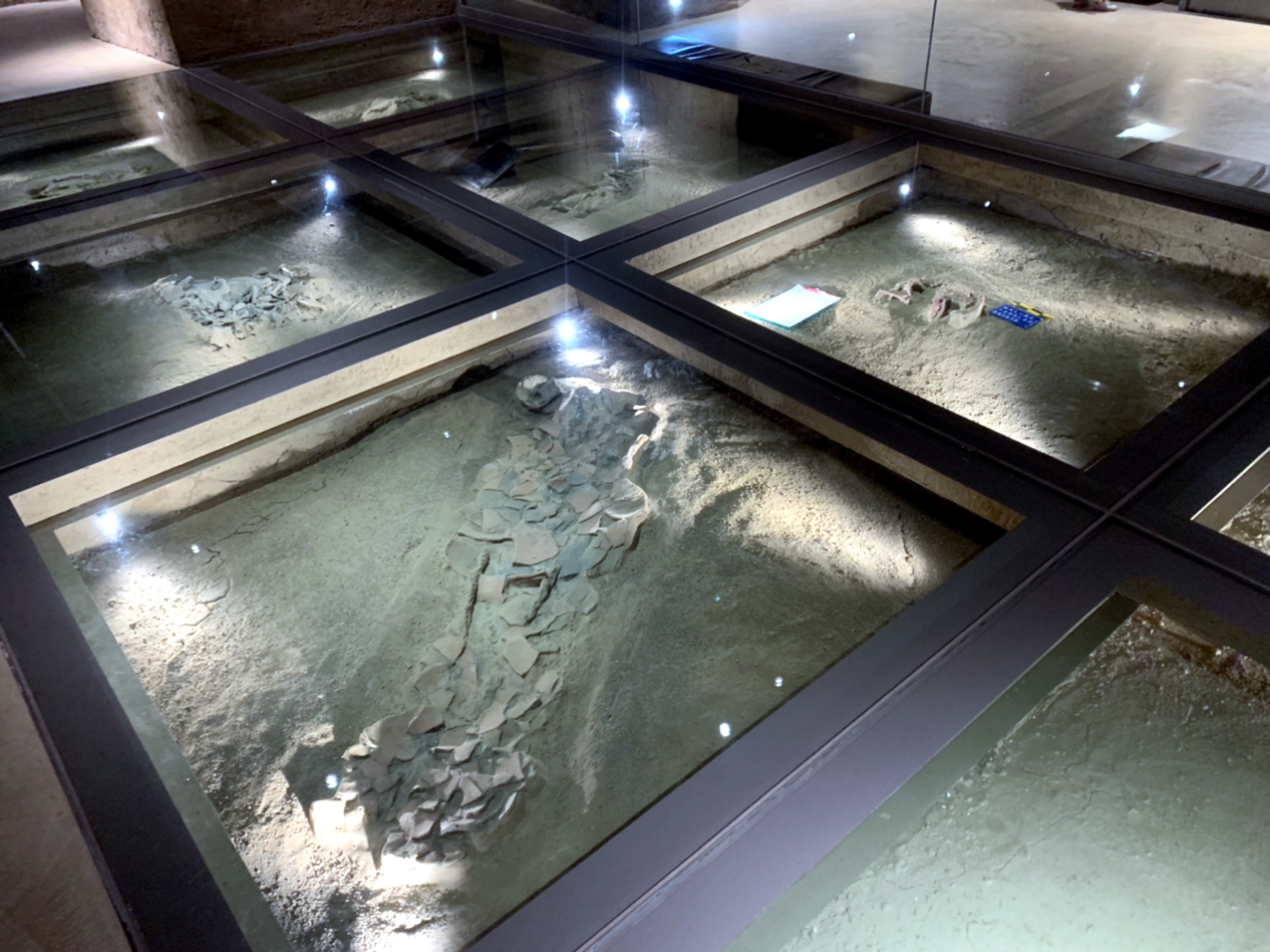

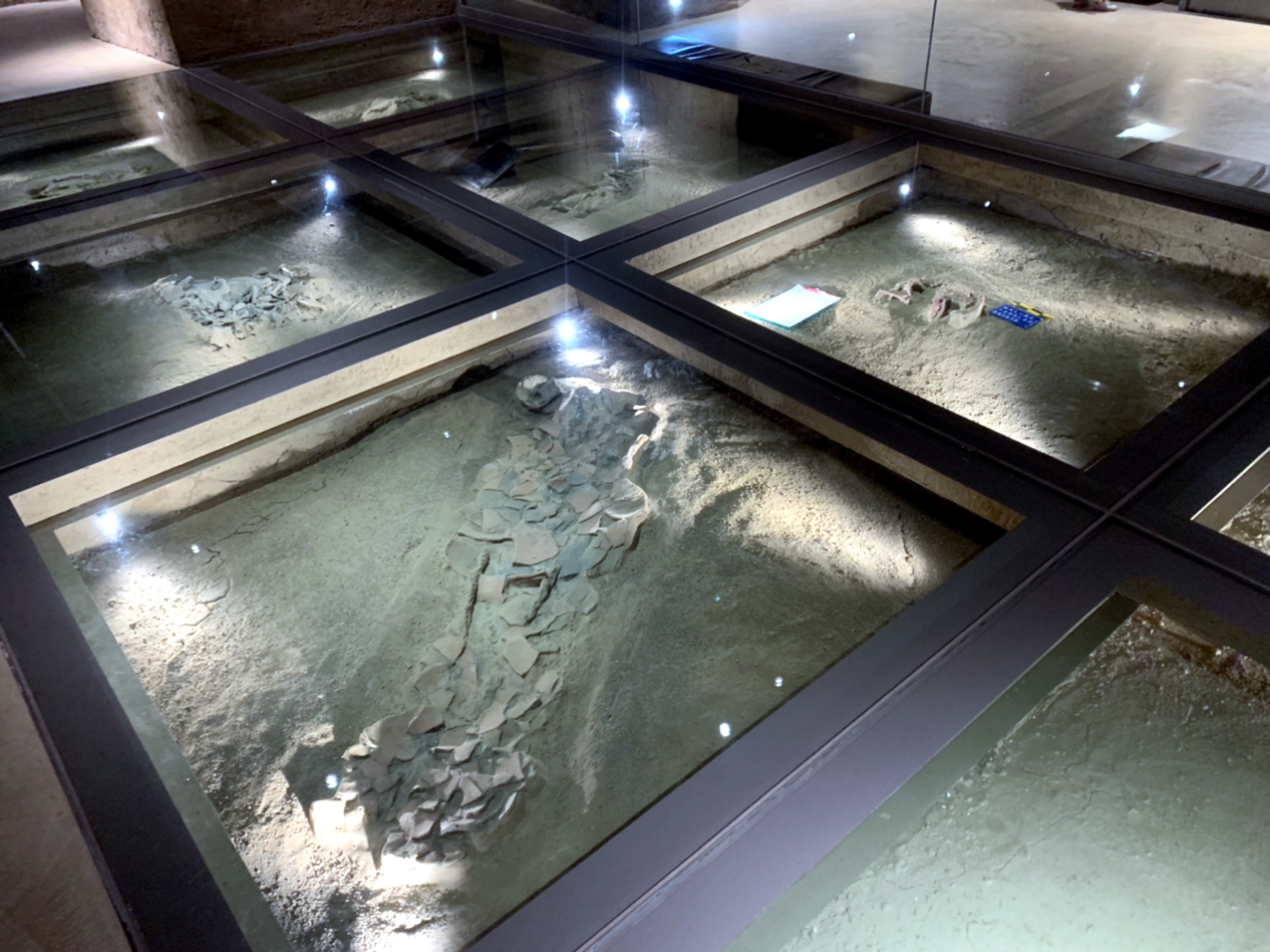

Some objects (which may be replicas) are even presented in ways that show how archaeological digs actually look -- there's an entire glass-floored room where you can walk over what would be the roped-off grid on a dig. I have a friend who's an archaeologist and I came away with a fresh appreciation for how she could look at, say, a specific shape of stone and identify it as a tool rather than just an interesting rock. One floor has dioramas -- along with real artifacts found in places that might have hosted scenes like these -- of how the people who used these items lived. You access each floor by going down a gentle ramp, as though you're descending through layers of the earth. The floors themselves are often made of materials meant to mimic a semi-natural, semi-industrial look. It is in a science park, after all, and the metal beams holding up all that glass on the way to the top remind visitors of that.

As you do, square windows offer odd light from a bright yellow courtyard. They're all at different heights and sizes, seemingly sprinkled down the hall. The effect is once again of peeking through at different levels of visibility, the way a reconstructed pot or a carved knife-handle might allow you to have a peek through a tiny window about lives lived in the distant past.

The courtyard itself is where all these windows converge, sunny-hued in even the cloudiest of weather. A single bench, a single beautiful tree, and several stories of viewpoints peering down at balanced but irregular intervals.

It's small and difficult to get to, but this is a museum worth visiting. This is a museum that incorporates its mission into its very structure, which attempts to reach out and engage you. This is a museum about Taiwan.

So what did I learn? Don't dwell so much on what is wrong -- though you can, if it's merited. Spend perhaps even a little of that time talking about what is right.