I was 19 years old, on my way to a study abroad program in India, and our plane from Los Angeles had a brief scheduled stop at Taoyuan Airport. As we cruised in, I saw rugged green mountain peaks jutting out from swirling white clouds and mist.

It was lovely, like coming across slabs of rough green and white quartz while hiking, but more vivid. Yet it was my first glimpse of Asia and second time to travel to another continent; it intrigued me.

Even Taoyuan Airport was of more interest then than it is now: a glass wall installation of Chinese calligraphy, a few shops, a new smell - my first whiff of the many scents of Asia which, while all different, are all entirely unlike those of North America. Perhaps now I find all this somewhat unimpressive - after all, who is impressed by Taoyuan International Airport? - but at the time I was taken.

One of my fellow India-bound students commented: oh, hey, we're in the Republic of China, cool!

Cool!

I knew that the People's Republic of China and the Republic of China were different entities, but I did not fully grasp all I did not know. I did, I admit, think of Taiwan as the place where Chinese culture had been "saved and preserved". Worry not, I grew out of that absurd notion. I thought to myself that, although this time we would not leave the airport, I would very much like to explore the Republic of China someday. The thought was, to quote my nascent inamorata, inchoate. But it was there.

I didn't go immediately - we stopped in Kuala Lumpur and explored the city for the day, went on to Chennai, then Mahabalipuram, then Madurai, India, where my entire worldview was turned on its head. I returned to the US and finished my degree, fighting what I thought might have been a touch of depression but was actually a compound case of senioritis and the travel bug. I went to China - the People's Republic of China, the other one - traveled around Southeast Asia, returned to India, then the US, then worked a stultifying office job for a few years.

And then, it was time. The opportunity was there in that I finally had the freedom and savings to explore this Republic of China, and I was fast realizing that what I thought was a temporary, curable travel bug was actually a chronic illness whose only cure was to leave and basically not come back.

Only then did I realize I wasn't going to the Republic of China at all; I was moving to Taiwan, or perhaps Formosa. But this was no China.

I am now an English teacher by profession, but I like to think (pretend?) that I am also much more than that.

* * *

Why am I telling you this?

Why am I telling you this?

Because almost exactly 100 years ago, the object of my affection boarded a boat in Manila bound for Nagasaki, passed Taiwan and noted how beautiful the cliffs plunging into the sea appeared:

Formosa, that little-known island in the typhoon-infested South China Sea, so well called by its early Portuguese discoverers - as its name implies - "the beautiful". Indeed, it was the beauty of Formosa that first attracted me....I shall never forget the first glimpse that I caught of the island as I passed it...there it lay, in the light of the tropical sunrise, glowing and shimmering like a great emerald, with an apparent vividness of green that I had never seen before, even in the tropics. During the greater part of the day it remained in sight, apparently floating slowly past - an emerald on a turquoise bed....

My desire to learn at first-hand something of the aborigines of Formosa remained, therefore, more or less an inchoate inclination on my part, and I turned my attention to other things. Then, curiously enough, as coincidences always seem curious when they affect themselves, a few months later...came an offer from a Japanese official to go to Formosa as a teacher of English in the Japanese Government School in Taihoku [ed: present-day Taipei], the capital of the island.

Girl, I already want you.

You floated by, I floated over, but we both had the same thought - there is a reason why they call this the Beautiful Island, and I would like to explore it. We both set that thought aside for years, and then, for both of us, the right circumstances presented themselves.

You floated by, I floated over, but we both had the same thought - there is a reason why they call this the Beautiful Island, and I would like to explore it. We both set that thought aside for years, and then, for both of us, the right circumstances presented themselves.

You even came as an English teacher, but you were so much more than that.

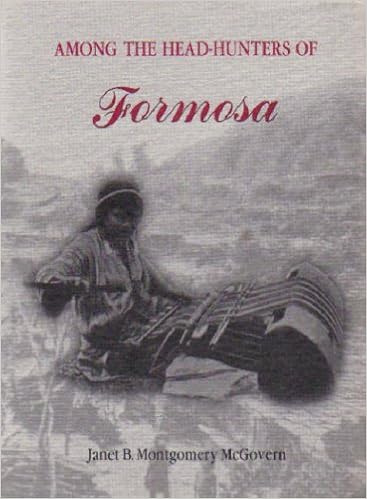

Let this be a lesson to those who would disparage all English teachers as losers, wash-ups, backpackers and weirdos: the single most awesome foreign woman to ever alight in Taiwan and write the classic but oft-forgotten Among the Head-Hunters of Formosa, merely because she was inclined to do so and found the place beautiful as she passed by once, was also an English teacher.

You were not wealthy (in fact, it appears you often published for general interest of of necessity, which may have affected your reputation enough to keep you from publishing in more scholarly circles). You were absolutely a wanderer, absolutely fearless, and absolutely unapologetic.

You were not wealthy (in fact, it appears you often published for general interest of of necessity, which may have affected your reputation enough to keep you from publishing in more scholarly circles). You were absolutely a wanderer, absolutely fearless, and absolutely unapologetic.

Brendan pointed out that you were the mother of William Montgomery McGovern, the possible inspiration for Indiana Jones. Although he did what a lot of adventurous male scholars were able to do at that time, whereas you bucked all sorts of expectations of women, let alone female scholars, and wrote a classic book on Taiwan, he has a Wikipedia bio, but you do not (guuuurl, I am gonna fix that for you, because you are my person.)

I am not concerned with your son, nor am I concerned with Indiana Jones. It's easy to have a crush on Indiana Jones. I have a crush on his mother who, by dint of what she did despite the sexist time and society in which she was born, was so much more of a bad-ass.

I can only lament that we were born a century apart. And that I like men, but that hardly matters: I'll make an exception for you, my star-cross'd love. If you weren't dead, that is.

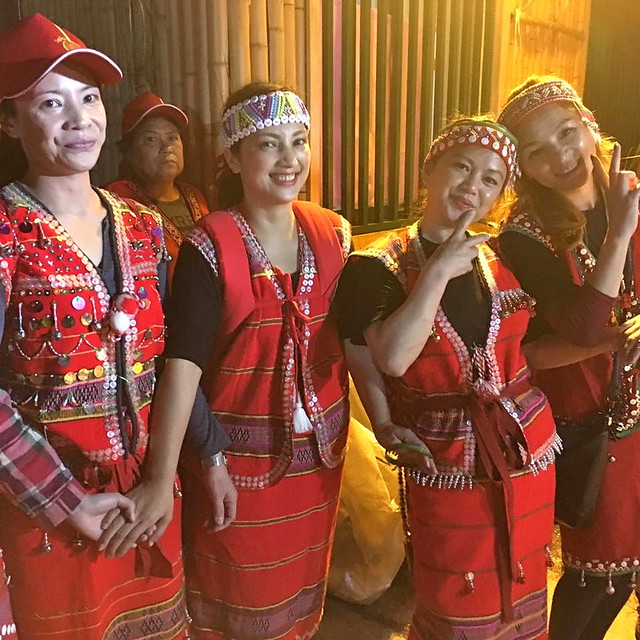

I am not going to recount the entire book for those of you reading this. It is available online, on Amazon, and can occasionally be found in Taipei (try The Taiwan Store). You will learn quite a bit about the indigenous people of Formosa: for a time, it is likely that nobody in the world knew more about them than Janet B. Montgomery McGovern. I especially enjoyed the marriage customs wherein a lovelorn "swain" (and yes, I adore the old-timey English usages) would play a small mouth harp or create a twenty-bundle monument of firewood for a woman's cooking pot in order to win her hand - and that she still had absolute right of acceptance or refusal.

Brendan and I decided to get married by basically saying to each other:

"We should get married, yeah?"

"Sure, that sounds cool."

So, this was nice.

Brendan and I decided to get married by basically saying to each other:

"We should get married, yeah?"

"Sure, that sounds cool."

So, this was nice.

But why am I so enamored with Janet McGovern?

She came to Taiwan as a single woman in a time when that was fairly rare - and when it was done, it was usually by missionaries. I love that she had no interest in being a missionary. She never seems to have become fluent in any one Formosan language, but picked up some of many different, rare tongues: more than wealthier expats with more resources today often manage to do for just one language, which is far more well-known, with more learning resources created for it, yet isn't even the native tongue of this country.

She came to Taiwan as a single woman in a time when that was fairly rare - and when it was done, it was usually by missionaries. I love that she had no interest in being a missionary. She never seems to have become fluent in any one Formosan language, but picked up some of many different, rare tongues: more than wealthier expats with more resources today often manage to do for just one language, which is far more well-known, with more learning resources created for it, yet isn't even the native tongue of this country.

She trusted head-hunters that full-grown men, both foreign and local, were terrified of, and was in turn offered trust, kindness and hospitality. She had such a no-nonsense, take-neither-shit-nor-prisoners writing style (I like to think I also have that style, updated for a new century?) that you could see, emanating off the page like waves of hot steam, that she was also a take-neither-shit-nor-prisoners woman. She totally DGAF before it was cool for women to NGAF.

Homegirl even said this to a Japanese official, in 1917:

I explained that obviously I was not a Japanese, also that I was not at all certain that I was a lady, and that if the distinction between coolie-woman and lady lay in the fact that one walked and the other did not, I much preferred being classed in the former category.

...Suddenly the light of a great idea seemed to dawn upon him. "Ah," he exclaimed exultantly..."but they will say you are immoral, and Christian ladies do not like to be thought immoral."

This struck me as being amusing - for several reasons.

"Yes," I said, "and who is likely to think me immoral?"

"Oh, everybody," he answered impressively. "And they will publish it in the papers - all the Japanese papers in the city, and in the island," he emphasized, "that you are immoral."

...."I am afraid I must continue to go on my wicked way without the protection of your companionship," I said; "and if 'they' - whoever 'they' may be - annoy you with questions as to the object of my excursions into the mountains....tell them 'Yes' to anything they ask about me," I said, "if that will set their minds at rest."

GIRL.

All I can say is this: Among the Head-Hunters of Formosa is an interesting book for its time-capsule like quality of describing Taiwan as it was in 1917, and is interesting for what one learns about the indigenous of Formosa, from a qualified anthropologist, although I would imagine much of the information is out-of-date.

But, I am a woman who once saw the beauty of Taiwan in passing and was inspired by that alone to make it my home, who DGAF or at least tries not to. I have some private but very few public role models of highly competent, fierce women of knowledge and training - remember, I am trained at the graduate level in Education, though I do not claim the same level of ferocity that Ms. McGovern clearly possessed - who have called Taiwan home among a sea of Western men, some exceptional but most mediocre. I loved this book, then, for reasons entirely separate from its ethnographic riches.

I also love it because I'm not alone. Janet B. Montgomery McGovern walked this path a century ago, and although she ended up at a different destination, so many of her landmarks are familiar to me even now. I have a deep sense of sympathy, although the experience does not mirror mine, of being the woman who should have run the whole show and had movies made starring characters inspired by her, only for that prize to go to her son.

My inamorata is not perfect. She consistently refers to non-aboriginal cultures as "more civilized", although she points out later in the book that the indigenous people she visited themselves viewed other cultures who don't keep promises as 'savages' and themselves as the farthest thing from. I won't excuse this by pointing out that it was a common line of thinking a hundred years ago. I will simply apologize as I like to think she would apologize now, were she still alive. Formosa may still be "little-known", almost as much now as then, but things have changed.

McGovern herself seems to grasp this toward the end, where she questions whether the "civilized" world would be better off, or how different it would be, if they followed the moral and social mores of the people she routinely refers to as "savages", and opines that, at least, it might not be worse: you might lose your head, but your community would provide for you, and everyone would say what they meant and keep their word. She also considers the idea of a matrilocal, matri-potestal "gynocracy" and what an evolution within such a system might have meant for Europe - in this part, you can see a glimmer of first-wave feminism shining through, and I love it.

Perhaps she goes too far in the other direction, making indigenous communities out to be more perfect - more "simple" in their "primitive" ways - than I think any society can actually be, but at least she considers it, which is more than I suspect many of her white male contemporaries were ever able to wrap their minds around.

And I have to admit, as I have said above, I have a bit of a crush on her, and this is my paean - no, my love letter.

But, I am a woman who once saw the beauty of Taiwan in passing and was inspired by that alone to make it my home, who DGAF or at least tries not to. I have some private but very few public role models of highly competent, fierce women of knowledge and training - remember, I am trained at the graduate level in Education, though I do not claim the same level of ferocity that Ms. McGovern clearly possessed - who have called Taiwan home among a sea of Western men, some exceptional but most mediocre. I loved this book, then, for reasons entirely separate from its ethnographic riches.

I also love it because I'm not alone. Janet B. Montgomery McGovern walked this path a century ago, and although she ended up at a different destination, so many of her landmarks are familiar to me even now. I have a deep sense of sympathy, although the experience does not mirror mine, of being the woman who should have run the whole show and had movies made starring characters inspired by her, only for that prize to go to her son.

My inamorata is not perfect. She consistently refers to non-aboriginal cultures as "more civilized", although she points out later in the book that the indigenous people she visited themselves viewed other cultures who don't keep promises as 'savages' and themselves as the farthest thing from. I won't excuse this by pointing out that it was a common line of thinking a hundred years ago. I will simply apologize as I like to think she would apologize now, were she still alive. Formosa may still be "little-known", almost as much now as then, but things have changed.

McGovern herself seems to grasp this toward the end, where she questions whether the "civilized" world would be better off, or how different it would be, if they followed the moral and social mores of the people she routinely refers to as "savages", and opines that, at least, it might not be worse: you might lose your head, but your community would provide for you, and everyone would say what they meant and keep their word. She also considers the idea of a matrilocal, matri-potestal "gynocracy" and what an evolution within such a system might have meant for Europe - in this part, you can see a glimmer of first-wave feminism shining through, and I love it.

Perhaps she goes too far in the other direction, making indigenous communities out to be more perfect - more "simple" in their "primitive" ways - than I think any society can actually be, but at least she considers it, which is more than I suspect many of her white male contemporaries were ever able to wrap their minds around.

And I have to admit, as I have said above, I have a bit of a crush on her, and this is my paean - no, my love letter.