She couldn't have engineered a turn away from Chinese identity because she was elected after it happened!

I keep trying to write this post, and I keep failing. Or something happens in my life -- this week it was a migraine -- and I sort of wander away. Part of it might be that I keep trying to give it an "article-like" opening even though this is a blog, and then I get bogged down in trying to sound a certain way, and it comes out all weird.

So, if I have any hope of saying what's on my mind, let's forget that and jump right in.

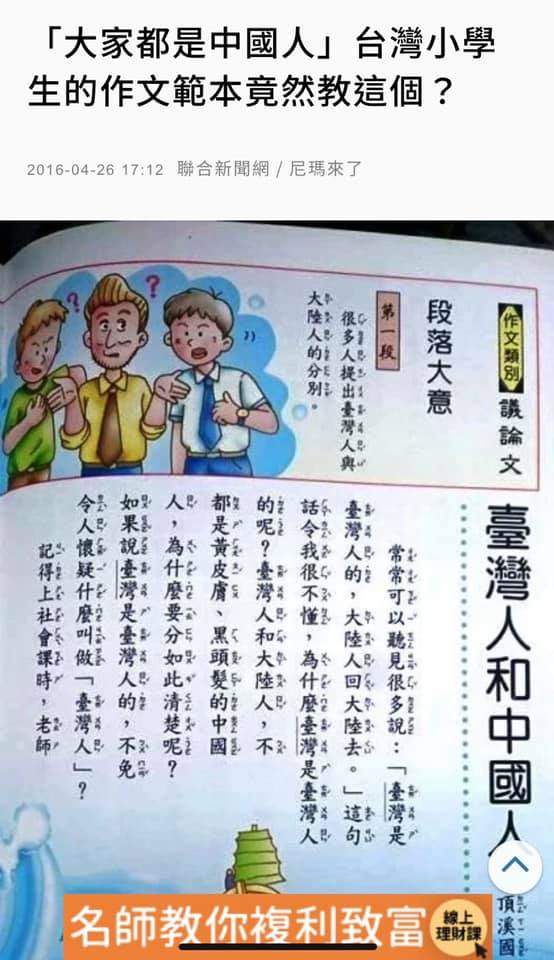

Anyone who advocates for Taiwan online will eventually come across a particularly virulent strain of poor reasoning and straight-up falsehood: that Taiwanese identity is robust because the DPP made it so, and that Chinese identity in Taiwan is on the decline because, again, the DPP "brainwashed" Taiwanese into thinking it was true. This is often used to lament the 'letting go' of an understanding that Taiwan is part of some concept of China, or 'forgetting one's roots' because data show Taiwanese in general have moved away from the notion that having ancestral heritage in China means they are Chinese.

I've been seeing it more these days, which might be attributable to it becoming a CCP troll talking point, though many real people seem to hold it as a sincere opinion. Another possibility is that it's harder than ever to point to unclear or inconclusive data to claim that, at best, Taiwanese don't know what they want. We know most identify as solely Taiwanese, and we now know that although the infamous 'status quo' survey is often (ahem almost always) poorly analyzed, that most people see the status quo as sufficient to consider Taiwan an independent country -- no name change needed.

Or maybe people are just jerks, or acting out the fantasies their KMT parents taught them, and pinning it all on the opposition. I dunno. I'd rather look at the problems with the argument than speculate about this.

Chinese identity is not the default

The first issue is easily dispensed with: "Taiwanese forgot their true heritage, that they are Chinese" absolutely begs the question. It assumes that the default state of Taiwan is Chinese identity, that Chineseness is the baseline, the neutral state, and any change from that is the only thing that can be "political", and therefore the only thing that can be engineered or forced onto a population.

This is wrong.

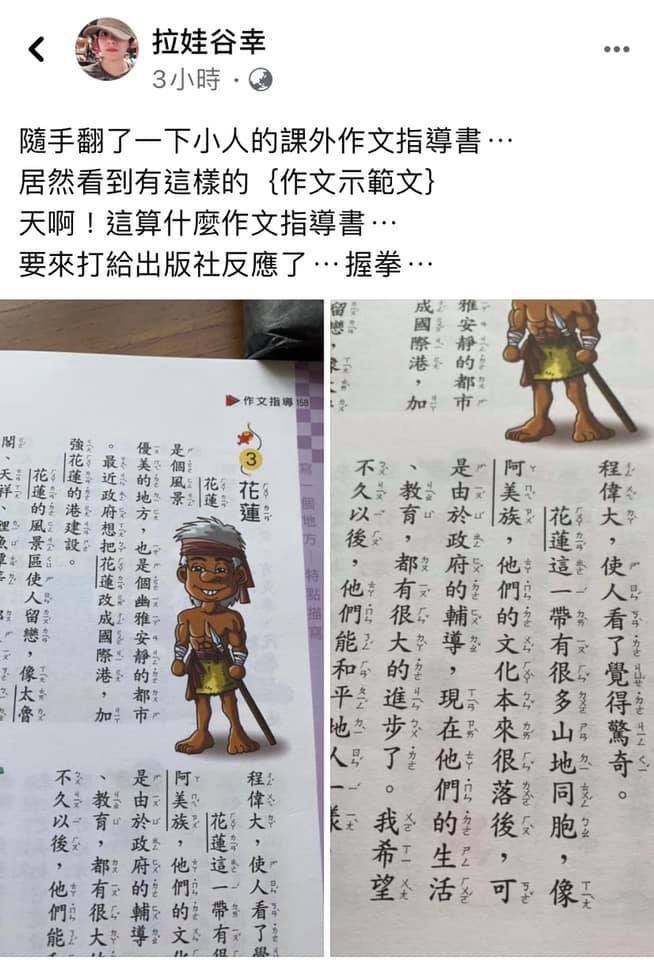

Remember when I said in a recent post that every KMT accusation is a confession? (Not originally my words, by the way). This is one, too. They accuse the DPP of using state power, including education, to force an identity on Taiwan. But that's what they did! The KMT implemented an education system that emphasized Chinese identity and either outright ignored Taiwanese history, or reduced it to a footnote within a greater Chinese framework. The KMT forced Mandarin on people who didn't speak it natively, actively banning other languages in school and government and highly discouraging their use in public (as in, speak Taiwanese or Japanese and we'll be watching you and maybe we'll send Officer Chang over to your house to check out your book collection, and if we can't find any "communist" literature we'll say we did anyway.) The KMT banned discussion of their own repressive acts in Taiwan. The KMT destroyed markers of Japanese culture in Taiwan, including not just language but modes of dress, temples and shrines. The KMT censored songs simply because the lyrics were Taiwanese, even if they held no inherent political meaning. In a twist that's going to matter later in this post, the KMT's own action to repress these songs is part of what led to them being used as acts of political symbolism!

Arguably, the KMT engaged in this far more than the DPP ever has, which I'll get into further down.

Unless you take as a default that Taiwanese should think they are Chinese, and therefore it's okay for the KMT to force that identity on Taiwan but not acceptable for others to deconstruct it, this is inherently a political and non-neutral series of actions. I don't take it as a baseline that Taiwan is Chinese -- and why should I? Most Taiwanese don't either! Besides, historically China either didn't rule Taiwan, or ruled only part of the island. To that end, Taiwanese history overlaps with Chinese only to a degree, and I'd argue it's not a very great degree. Most of Chinese history is not relevant to Taiwan (just about anything up through the Ming Dynasty) unless you're talking about ancestral, not national, history as the island of Taiwan wasn't ruled by China in those centuries. And the few centuries where they do overlap, well, China not only didn't rule the whole island for the most part, they treated it as a backwater worth little attention and even fewer resources.

Perhaps the settlers' ancestors came from China, but from a political perspective, that ceases to matter after a few generations. The 1949 diaspora came more recently, but they were always a minority and their grandchildren have closer ties to Taiwan for the most part. It's fundamentally a flawed assumption to believe Chinese identity in this circumstance is immutable.

So, what is the default identity for Taiwan?

The default identity for any group of people is what they want it to be. Not in an "I'm 1/16th Cree so I have decided I'm First Nations even though I don't participate in the culture and have always been treated as white" way. I mean in a "we live this identity and bear the full weight of it, so we get to decide what it means" way.

Whether it's Chinese people furious that Taiwanese don't see themselves as Chinese, or white wannabe anti-imperialists who talk big about accepting different identities unless that identity is Taiwanese, in which case suddenly 23 million people don't get a say, it astounds me how people can be so two-faced. That is, talk one minute about how nobody else can tell others who they are or dictate their history to them, and the next about how Chinese say Taiwanese can't be Taiwanese, so we can't recognize Taiwanese identity out of respect for China.

How is it not just important but imperative to respect every identity, but then whip around and call Taiwanese identity separatist, ethno-nationalist or even Sinophobic/anti-Chinese?

How can you insist, if you are Chinese, that nobody else can explain your heritage and culture to you (which is true) -- and then feel comfortable explaining your version of Taiwan's heritage and culture to them?

If you're not Chinese, how can you go around insisting everyone respect gender and sexual identity, heritage identity and neurodivergence (all great things to respect, and I agree) and then dismiss Taiwan as the one identity you don't have to respect?

If you're an Asian American, how can you consistently leave Taiwan out of identity debates, and in some cases simp for the Chinese government, totally disrespecting your fellow Asian Americans who happen to be Taiwanese?

Finally, if you're Taiwanese American (including the descendants of the KMT diaspora), how cam you tell Taiwanese in Taiwan that your grandparents' vision of an island they only briefly inhabited is the only correct one, and they better fall in line? How can you insist that your legitimate and valid view of yourself as Chinese must therefore apply to all Taiwanese?

It boggles the mind! If Taiwanese say they are Taiwanese, fucking listen to them.

(If the majority said they weren't Taiwanese, you should listen to that too. But they don't.)

This is especially true as the tenor of pro-Taiwan discourse has trended increasingly towards accepting that some portion of the population will disagree. This is fine, as people have a right to their own views and identities. It is imperative, however, for the pro-China side to offer that same respect. Currently, I don't see that this is the case.

Seriously, I'm starting to think the fastest way to tell a real anti-imperialist for a straight-up fraud -- or a truly socially-conscious person from a self-righteous jerk -- is to bring up Taiwan. If you're not interested in respecting Taiwanese identity, I now assume you are a hypocrite who doesn't respect identity unless you personally approve, and therefore not worth my time.

Get your timelines right!

The final issue takes longer to talk about. It's a straight-up reverse cause fallacy in which time, for people who believe the DPP "forced" Taiwanese into "forgetting they are Chinese", apparently moves backwards. Or at best, it might be considered a cum hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy in which one historical trend is falsely fingered as the cause of another roughly concurrent trend.

For the DPP to credibly be the evil masterminds engineering Taiwanese identity, they'd need to be in a position of sufficient power or influence before the movement away from Chinese identity and toward Taiwanese. Otherwise, how could they have effected the change? With what exactly would they have forced their nefarious plan through, protest signs and...frequently getting arrested?

Seriously, just look at the timelines. In what years did Taiwanese identity spike? First, starting around 1995, when it overtook solely Chinese identity, and climbed steadily until 2000. That's significant, and I'll talk about it in a moment.

It overtook "Taiwanese and Chinese" identity between 2006-2008. At that time, the DPP's star was falling thanks to the rumors swirling around Chen Shui-bian, reaching what might be described as a nadir with the election of Ma Ying-jeou.

A lot of people seem to think Chen was some sort of ogre forcing Taiwanese identity through schools and society, but during his presidency, Taiwanese identity rose far more slowly than in the preceding years, with a few dips. If he was trying to evil-villain Taiwanese identity to greater prominence, he didn't do a very good job. How could he have, when the legislature was still KMT-controlled?

The next significant spike hit around the Sunflower Movement, with the increase leading up to it following the descent of President Ma into deep unpopularity. "Aha!" you might shout. "It does follow the rise and fall of political party influence!"

Not so fast. Ma was still in power, and the legislature majority KMT. People often reference education as a site of struggle where these sorts of so-called "brainwashings" are engineered, but Ma's big education policy was to make the curriculum emphasize links with China, not Taiwanese identity! If anything other than the Sunflowers led to a spike in Taiwanese identity (and there was one), it was the electorate's reaction against policies like this, not the government's evil plotting.

Besides, if the DPP were able to control local identity so much before Ma, then how did Ma get elected in the first place?

The Sunflowers themselves wielded a great deal of cultural capital but not much institutional power, so while they certainly impacted the national conversation and societal beliefs, they could not have engineered or masterminded any sort of authoritarian changes intended to "brainwash" anybody. They occupied the legislature but weren't elected to it. They protested lawmakers, they weren't lawmakers themselves.

Some will still claim that perhaps it wasn't Lee, or Chen, or the Sunflowers responsible for this "brainwashing", but Tsai. If that's so, explain how Taiwanese identity actually dropped a bit in the years following her election -- that is, when she began to actually wield power?

It's true that the most recent spike occurred around the 2020 election, gathering momentum from its 2018 "nadir" (well, compared to the years surrounding it. Overall it was no nadir at all.) But Tsai was already in power then and had not managed to elevate Taiwanese identity in the previous two years. It's unlikely that her knockout defeat of Han Kuo-yu and re-election caused this spike. Rather, they were probably the result of it. Fears about China and the overall incompetence of the KMT candidate are more likely possible causes.

Think about it: in what universe does "you elected me, therefore I will brainwash you" make any sense? Just in terms of, y'know, linear time?

To put it succinctly, if the "evil DPP" was "brainwashing" Taiwanese into thinking they were Taiwanese, how is it that Taiwanese identity hit milestones around the time KMT presidents (and legislatures) were elected, and leveled off or dipped a bit after DPP ones were?

It's not even post hoc reasoning. It's just backward.

More likely, these changes occurred naturally, and the DPP was the beneficiary of changing public sentiment regarding identity, not its architect. Just as likely, they were a reaction against the newly-elected KMT turning back towards China once again -- so if anything caused a shift toward Taiwanese identity, it was probably (and unwittingly) the KMT!

Let's rewind. What happened in 1995, when that first spike happened? Well, Lee Teng-hui offered imminent democratization, and the Third Taiwan Strait Crisis. Who got elected in 1996? Lee, who despite ushering in a more nativist approach, was KMT, not DPP. Who controlled the legislature and most mayoral posts? The KMT, though the DPP had a loud minority and the coveted Taipei mayoralty. A voice, but a minority or subordinate one in terms of power structures.

If it could not have been the DPP -- again, they lacked the actual power -- and the KMT was, if anything, reacting to a broader social change, the only reasonable explanation for the shift towards Taiwanese identity is probably best explained not by the machinations of political parties, but democratization in general. Democracy: that amazing thing where either party can be elected!

No, education is not the cause -- it's the effect

"But the education system was changed to emphasize Taiwan in the 1990s," some might shriek. "The evil DPP pushed for that, it's their fault!"

Not really, though. Yes, textbooks were slowly deregulated and curricula decentralized. Local history and "getting to know Taiwan" were introduced. The 228 Massacre could finally be discussed, and the role of local languages in education debated (the preeminence of Mandarin still remained, however). But the authorities allowing these changes on their preferred timeline were the KMT, not the DPP, though you could say they were forced to make concessions to the opposition and even adopt some of their nativizing rhetoric into their own platforms as a result. Do not forget, however: the KMT retained most of the actual power. What's more, these changes merely allowed Taiwanese history, society and geography to be discussed in an expanded version of a "local curriculum" where Taiwan was still ultimately treated as part of a larger China, or as the site of the ROC on Taiwan, not a nation in its own right.

If simply talking about Taiwanese history and not hitting or fining children for speaking their native languages in school is enough to turn people from Chinese identity to Taiwanese, then Chinese identity in Taiwan must have been resting on pretty weak legs to begin with, eh? Maybe that alone could topple a popsicle-stick house, but not a monolith. So either it wasn't the cause, or Chinese identity was a stick house. Regardless, the final authority that approved these changes was the KMT, not the DPP -- a KMT reacting to this social change to retain power, not engineering it.

In other words, democratization, national educational curriculum changes and the move toward Taiwanese identity all happened around the same time. They probably didn't cause each other (although if any one of them is a root cause of the others, it's probably democratization -- don't quote me on that, though). The common cause of all of these effects was a reaction against decades of brutal, repressive KMT rule and enforced institution of Chinese identity, not some sort of evil DPP plan. Not only is there nothing wrong with wanting to learn about one's local history, but a push to do exactly that -- and decouple that history from some larger story of a larger civilization as well as talk about the parts of that history that don't overlap with it -- usually follows a change in identity. It doesn't cause it.

That's the case, at least, when the push to do just that comes from a newly democratized society, or a minority voice in the government who can't change the rules at will. Chinese identity through education was a top-down project, fed to schoolchildren through the education system by the KMT. Taiwanese identity entered the education system from the bottom-up, when the DPP didn't have institutional power.

A quick summary for the tl;dr crowd

The DPP certainly played an important role in pushing for democratization and being that minority voice once the KMT stopped arresting and torturing them (though remember, the last political prisoners were still in jail in the early 1990s!). They pushed for changes to the education system, but ultimately needed KMT acquiescence to realize them. The KMT caused a backlash thanks to its own repressive rule, and stands guilty themselves of forcing Chinese identity on Taiwan, which was not a neutral act as Chinese identity was not the default state in Taiwan any more than Mandarin was always the lingua franca (it wasn't). Even if you try to argue it by timeline, it doesn't match up and if anything is backwards reasoning.

Whatever you want to name as the cause or origin of Taiwanese identity, it was not the DPP. If anything, they were an effect of that change, and to some extent, you can say the KMT did this to themselves.

But really, if you absolutely need a "cause" (do you?) -- look no further than democratization. Do you hate democracy? I sure hope not.