As I head back from a combination business trip/mini-vacation in southern Taiwan, I thought it would be a good idea to highlight three excellent articles about Taiwan by three smart women who care about this country, and tell you whyI like them so much. If you’re interested in changing perspectives on Taiwan, including through foreign voices, all three are worth reading. Sadly, two are behind paywalls, but if you have free articles left with the New York Times and Asia Nikkei, these are worth the views.

First up, let’s talk about What Taiwan Really Wants. This editorial by Natasha Kassam in the New York Times does an excellent job of framing the issue.

A key quote for anyone who can’t get around the paywall:

The status quo means maintaining de facto independence but avoiding retaliation from China. And the percentage of Taiwan’s people who want to maintain the status quo indefinitely is growing. It is the best-case scenario in a sea of unenviable options.

To be sure, if there were no risk of invasion from China, the majority would choose independence.

But China’s President Xi Jinping has made clear that such a declaration is not available to Taiwan. So the status quo is pragmatic — and preferable.

This is succinct, expert analysis which acknowledges the role of the ‘status quo’ while clarifying that a preference to maintain that status quo does not mean that there is no consensus on sovereignty or unification.

Certainly, not everyone is on the same page. In any society there will be a range of opinions. However, stopping at “most people prefer the status quo” makes the issue sound far more fractious than it really is. The truth is that most people prefer sovereignty and peace — not just one or the other — and if the only available option is this “status quo”, they’ll take it.

It’s also about time we acknowledged that the way the questions on the “status quo” survey are worded push respondents toward choosing it. Almost nobody wants to choose unification, but there’s no option for choosing “independence, but without fighting a war.” I'm not the first person to point this out, either.

Participants are never asked what they’d prefer absent a threat from Beijing — which is to say, what they ideally, actually want for their country. It's not a pointless question: it's the only type of question that attempts to probe respondents' true desires. Currently, every answer clearly leaning toward “independence” carries an implicit acknowledgement that war might be a part of that choice.

What people are trying to say here is that they want both. They want better options, but ultimately, the status quo is sovereignty.

Pretending otherwise does a disservice to Taiwan. It relegates “pro-independence” sentiment to only a narrow set of views, when actual pro-independence Taiwanese don’t necessarily fit in those boxes.

We know this because those same Taiwanese who say they “prefer the status quo” also identify as solely Taiwanese or prioritize Taiwanese identity. People know what they want. Listen to them.

Here is how you can tell Kassam is a true expert: it took my several paragraphs to say that. She clarified it in half the space, without falling into the trap that fells so many analysts: the idea that “the status quo” represents indecisiveness, or that the survey in question even has construct validity. In my opinion, it doesn’t — the questions don’t actually ask what interpreters of the survey think they do.

Next up, Rhoda Kwan writes about the erosion of the Taiwanese language in public spaces for Hong Kong Free Press. This is an excellent piece both for the clarity with which it discusses Japanese and KMT linguistic imperialism, while pointing out that attitudes today, influenced by past authoritarianism, are also barriers to making Taiwanese mainstream in all situations, including formal ones.

Hong Kong Free Press has no paywall, but here’s a key takeaway:

The academic’s attempts to use Taiwanese in his daily life have been polarising. Although some Taiwanese have hailed his efforts to engage with a long-oppressed facet of Taiwanese life, some have also taken offence at his use of the language in professional settings.

“Some Taiwanese stigmatised the language and believe that it should not be used in formal situations,” he told HKFP. “I had an experience in southern Taiwan where a Taiwanese said to me angrily, ‘How can you speak the Taiwanese language in such a formal situation? I am very surprised that the university employed this kind of faculty member!'”

This anger speaks to the threats facing the Taiwanese language in the island today, where its use is almost confined to certain social milieus.

“You often hear construction workers or police officers speaking Taiwanese… so there’s always been these environments [to speak it], even though it’s been formally suppressed,” Catherine Chou, a Taiwanese-American history professor, told HKFP.

That’s the tricky thing when a language becomes very context-specific, there’s the danger of actually losing it, because the mentality becomes ‘It’s not for general use, it’s for the home, it’s for very specific business relationships, it’s for people that I know, it’s not for people I don’t know’,” she continued.

This is fantastic because Chou (who is quoted here) is right. I say that with the full force of someone who actually is an expert in this stuff: I’m a die-hard social constructionist and interactionist. And that’s the core of it: you need meaningful and varied opportunities to use a language as well as the motivation to actually do so in order to attain a high proficiency level.

And the attitude that Taiwanese is for family and friends and informal situations — a ‘kitchen language’ — is now the obstacle that must be overcome. If initiatives like Bilingual by 2030 are to truly give languages like Taiwanese adequate resources, this needs to be taken into account.

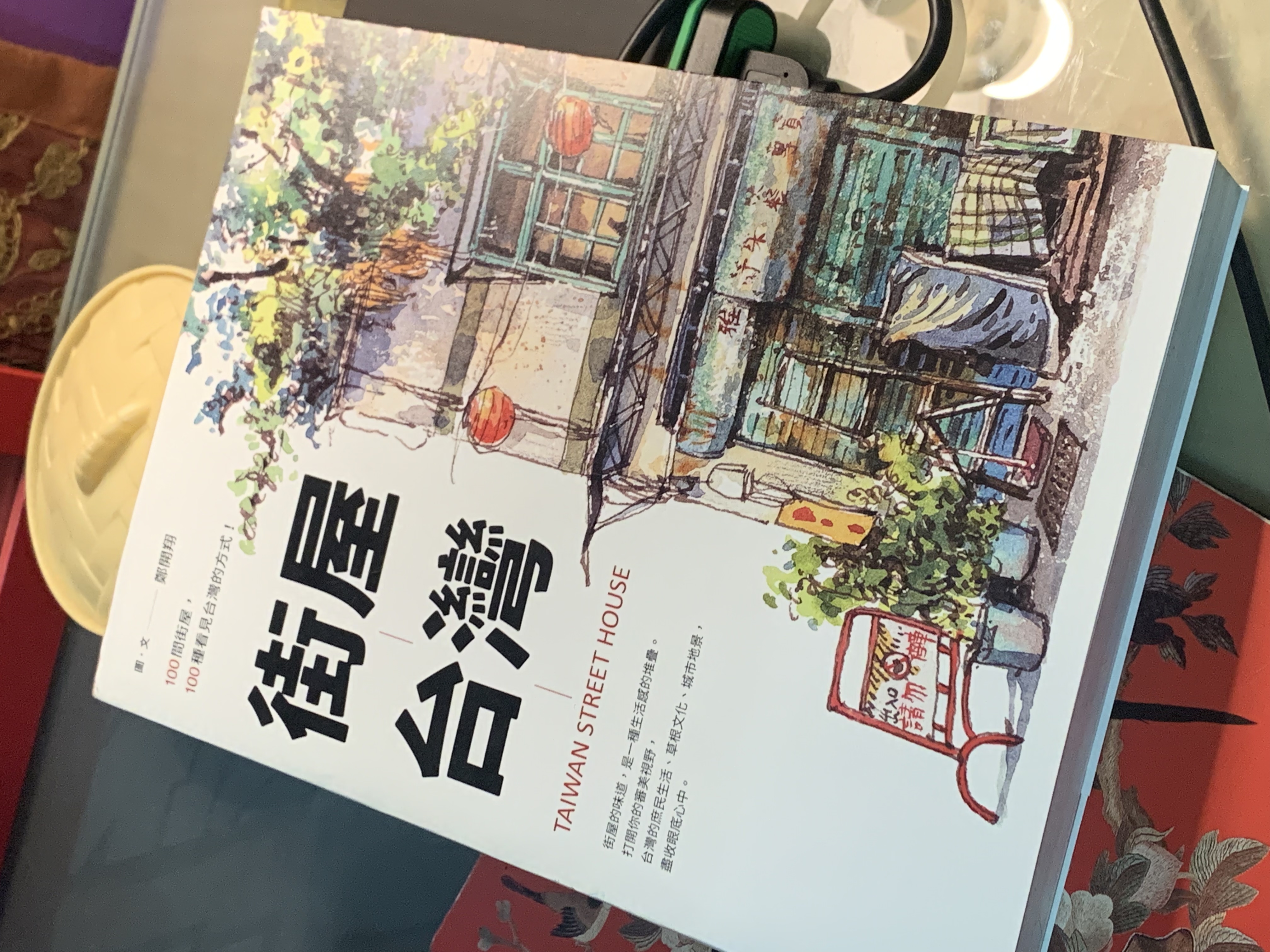

Finally, Erin Hale talks about “Taiwan’s Enduring Fascination with Japanese Architecture” in Nikkei Asia.

This is a fantastic piece because it uses architecture in an immediately relevant way to deconstruct the half-hearted screeching of online tankies and trolls.

Ever heard one of them whinge about how Taiwanese still have “colonized minds” because they wish they were still ruled as a colony of Japan? I have. But it’s not remotely true: the underlying assumption here is that thinking of your cultural heritage as partly Japanese is “colonial”, and thinking of it as uniquely Taiwanese is “separatist” — the only way to properly think of one’s culture, according to these people (or bots) is to consider it wholly and unchangeably Chinese.

But Taiwan is more than that, and Taiwanese history proves it. Acknowledging one aspect of one’s cultural heritage is not the same as idealizing a former colonizer.

Hale lays this out well:

To many Taiwanese, however, these buildings represent a new "Taiwanese identity of pluralism" where Japanese cultural influence is "not seen as a foreign element that's going to dilute Chinese culture" but as part of a more complex identity for the third-wave democracy, said NTU's Huang.

But, Huang warned, by embracing Taiwan's past, people should not over idealize it. The Japanese era is remembered so well in Taiwan in part because of the martial law that came after it, not because of the innate superiority of Japanese culture or governance.

She also lays out the problems with architectural restoration: it’s expensive, and there are a lot of buildings which were left to rot by the KMT as a form of replacing Japanese influence with Chinese. The lack of maintenance makes them even harder to restore. There are only so many Japanese cafes and restaurants in restored buildings that a country needs, but allowing private companies to do the restoration with the government as a ‘landlord’ has worked in a few cases.

I’d also add that some of these buildings have been turned into museums, like the Railway Department Park, which was carefully restored in conjunction with the National Taiwan Museum just up the road.

There you have it — three great writers and analysts, three great pieces, three things worth reading this week. Every one of them evidence that discourse on Taiwan is changing.