Awhile back, I went out and bought Cathy Erway's

The Food of Taiwan (despite the annoying Tom Sietsema review on the back that condescendingly called Taiwanese food a regional Chinese cuisine - ugh, no, because Taiwan is not a region of China - but he didn't write the book so whatever.) I didn't make anything from it for the longest time, though, because despite being a damn good cook, I had always figured that I should spend my precious cooking time on food I can't get outside, or no restaurant I've found can make as well as I can (just try to find a brown rice pumpkin risotto with saffron and sundried tomatoes - you can't, unless you come over for dinner). Why make myself what I can get better and more cheaply outside?

Recently, though, I've reconsidered that position. It was starting to feel embarrassing that I'd been here for a dozen years yet hadn't learned Taiwanese cooking, despite being great in the kitchen. Other cuisines I've learned because I've lived in those places - e.g. Sichuan/Guizhou food, Indian food - I learned after I left, to my detriment. It was time to fix that, and learn how to make Taiwanese food in Taiwan. If anything, simply to better understand the culture I live in and try to be a part of in whatever limited way I can and am welcome to do so.

So, I cracked open

The Food of Taiwan and set myself the task of making a selection of dishes from it. Essentially starting from a place where I knew what the food ought to look and taste like, but learning what makes it that way.

I approached the book knowing that her recipes would not be the final authority on how to make any one dish, but as a good English-language resource, as the only recipes I could find online that were any good were in Chinese. I can roll with that, but it's just easier to follow something in my native language.

I also planned to try any failures at least twice: I may know what they are meant to look and taste like, but that didn't mean I wouldn't get them wrong the first time around (and I did get a few wrong).

My overall impression? No one recipe is dead on, although some are very good. Often, the ingredient proportions or cooking directions weren't quite right (or didn't work with my kitchen equipment), in other cases, the ingredients called for didn't quite make sense. Some were acceptable variations, but at least one was completely off. (There's "normal variation" and then there's "every person I asked about this recipe shook their head in disbelief or wondered if Erway had ever actually had the real dish").

This cookbook is clearly meant more for cooks in Western kitchens going to the Asian supermarket for ingredients - which makes sense, as the market for a cookbook of Taiwanese food in English for foreigners in Taiwan is perhaps...uh, not that large. This was evident in some of the names of dishes ("Taiwanese burrito" for 潤餅 - huh?) But, for the cook who can just go to the traditional market or dry goods shop and get what she needs, there are unnecessary shortcuts and a few instances of confusing labeling.

So, here's what I made, and how it turned out:

Spicy marinated cucumbers / Cold pickled cucumbers (酸辣小黃瓜)

|

| I like scallions on mine, too. |

This was one of the most successful dishes, although I have to admit I've been making it for ages - one of the few Taiwanese dishes I consistently put together. I happen to prefer to mix the salt, vinegar, sugar and other ingredients all at once, and refrigerate for a few hours. However, both Erway's version (which calls for salting the cucumbers first) and mine work just fine. I don't de-seed my cucumbers as I usually eat them same day, but if you're going to save them for a few days, it's a good idea. I also prefer more vinegar - I practically submerge mine rather than just using two measly tablespoons. That, however, is a matter of taste.

What I found odd was the addition of chili bean sauce (a condiment I feel Erway invokes far too often where it is not needed). These cucumbers are much better with chopped, de-seeded long red chilis. I was also confused by the leaving out of garlic - a burst of fresh garlic paste (or coarsely chopped garlic) added to the marinade makes the dish. Also missing is a topping of fresh cilantro, but that too is a matter of taste.

Because these cucumbers are (almost) as common a side dish as kimchi in Korea, the last time I made them I was reminded of something David Chang said not long ago: that he used to think

white people shouldn't make kimchi. Later on late night television he walked that back, noting that if a white person makes Korean food really well, they might become a major advocate for the cuisine and that can only be positive - and in any case, I suspect he was talking about

chefs making kimchi, not regular home cooks.

That comment got me thinking about being a white lady who often cooks Asian food - I may be new to Taiwanese cooking but I frequently cook dishes from other parts of the continent, most notably Indian. I understand the criticism of white chefs cooking traditional foods of people of color while the people of color themselves continue to be discriminated against for their non-white cultures and appearances - that is, making a profit off of something that when the originators of that thing are still otherized for having created it. However, I don't see a problem with my making Taiwanese dishes for myself - after all, I live here. Should I bar myself from learning how to cook locally because I'm not a local? Would any local think that a decision to remain ignorant of local culinary techniques because of my race was anything other than utterly ridiculous? I doubt it.

I've yet to meet real-life people who think otherwise, although I'm sure they exist.

In any case, I think as long as you aren't profiting off of someone else's culture while otherizing people from that culture (seriously don't do that), if you make the food well, you're fine. The proof is in the Hakka stir-fry.

Basil clams (塔香蛤蜊)

|

| Needs more basil and soy sauce, less alcohol |

This recipe was one of the closest to dead-on in terms of the flavor I've come to expect from eating this dish locally. There were no unexpected additions to the ingredient list, nor anything I felt was missing. However, the proportions seemed a bit off: the final flavor was far more alcoholic and not salty enough. The dish was successful enough that I didn't feel I needed a re-do, although I do intend to make it again simply because I like it. When I do, I'll reduce the rice wine from 2 cups (!) to 1, increase the soy sauce from 1 tablespoon to closer to a quarter cup - or use regular rather than light soy, or both - and make up for any lack of liquid with water. I also felt the dish needed more basil - about twice what is given on the recipe.

Be careful when making this one, as the clams are essentially cooked in rice wine, and...well I wouldn't know anything about any small kitchen fires that may have happened when a little bit of the alcoholic steam condensed and ran down the side of the pan and ignited...no sir.

Other recipes add one ingredient Erway leaves out: sliced ginger. Trying to hew as closely to the recipes given as possible, I too left it out, but will add it next time.

After all, one of the things I've learned while living in Taiwan is that there is just as much individual, family and regional variation in cooking as there is in the US. It does seem sometimes as though Westerners who think themselves worldly 'flatten' the part of the world they don't live in: where they are from, they recognize that one dish can have a thousand variations. Everyone and their grandmother has a slightly different recipe. But get that same Westerner abroad and they think the food of the place they are visiting has only one "traditional" way of being made, with all others being "wrong" somehow. Like each one must either be the Platonic Form of itself, or it's a bastardization by someone who doesn't know better. So they rank different restaurants in, say, Vietnam by how 'traditional' their Vietnamese food is, when as far as I see it, if it's a restaurant in Vietnam serving Vietnamese food, it is authentic Vietnamese food. What else could it be?

So ginger, no ginger, whatever. Do what you like (but I seriously suggest a little ginger.)

Braised meat rice (滷肉飯)

|

| This tastes so Taiwanese - braised egg was my idea, and it was a good idea |

This is one of the dishes where there seems to be the most individual variation. One of my Taiwanese friends adds preserved tofu (豆腐乳) to give the dish depth. Another uses lean meat for health, and yet another adds chopped mushrooms. A Taiwanese friend who is an actual chef adds licorice root (甘草) and dried mushroom. There is a very good restaurant on Yanji Street whose 'signature' dish is braised meat rice, but including half a hard-boiled egg and shredded chicken. Some people serve it with a Taiwanese-style pickle (which I like - and you can buy them cheaply at any supermarket). Others add cilantro (I'm also a fan.) Many online recipes call for cooking the meat first, and using the pork fat to cook the garlic - and many call for adding the white part of a green scallion at this stage (I did this the second time around and it worked well).

I tried this dish twice, as the first one came out far too thick and salty - the second time using lean meat and chopped mushroom to 'imitate' the fat I was leaving out, and it tasted both wonderful and authentic. It was a reminder that I might know what a dish is supposed to look and taste like, and I've been here for awhile, but that doesn't mean I'll get it right the first time around.

My only quibble is that the first time, I simmered it for between 1-2 hours as Erway suggests. It thickened far too much and I found I kept having to add water to it - and it wasn't necessary as the cut of meat I'd bought was pretty good - I generally don't have meat scraps lying about as we often eat vegetarian at home. However, she was absolutely right in her suggestion of the proportions of low-sodium soy sauce to regular soy sauce.

Thick soup with meat (肉羹 - though I ended up actually making cuttlefish thick soup or 摸魚羹)

|

| The carrot was not necessary, and I like more vinegar and white pepper than Erway does |

I didn't make the fishcake-coated pork shoulder because I was short on time, so I bought pre-made cuttlefish cakes to add instead and they were fine. Otherwise, this recipe worked well, although I found the amount of cornstarch listed did not turn the soup sufficiently "thick", and I ended up adding more. I also added the noodles directly to the soup as the sizes they came in didn't work well for portioning into bowls.

This is one which created a bit of a labeling kerfuffle - Erway calls for "black rice vinegar", but just try finding something labeled that at a Taiwanese supermarket. They have it, but it's labeled 烏醋, not 黑米醋 (as one might find on Hong Kong brands if one Googles). Complicating this, some brands of black rice vinegar in Taiwan label it "Worcestershire Sauce", which I don't think it is, exactly. I knew this, but someone who isn't aware might spend quite a bit of time looking for something that is simply labeled differently.

There is at least one other thick soup recipe in the book, for squid - and I appreciate that the two are different rather than just "make thick soup, add thing you want".

The recipe calls for 1 tablespoon of the vinegar and one of sesame oil for the whole large pot - I like a bigger dose and actually add a lashing of vinegar to thick soup when I eat it out, so I added quite a bit more to my bowl, along with a sprinkle of white pepper.

The carrot could be left out, but the bamboo and shiitake mushroom are, to my mind, essential. I left out the cabbage because cabbage makes me fart. I mean like to a concerning degree, to the point that my husband replies to my farts as though I am talking to him (like this:

Me: *

frrrap*

Brendan: "That's not true!")

I once saw a doctor about it but he said nothing was wrong with me, I'm just, like, fartier than average.

So...no cabbage.

Sweet potato leaves (地瓜葉)

|

| The garlic is a weird brown color because this was my second attempt, and I found I preferred it with soy sauce instead of salt |

You'll be surprised to hear that this - the easiest Taiwanese vegetable there is - was one of the recipes I struggled with. The leaf wilts very quickly and grows bitter if you overcook it. The stems, however, never quite seem to be fully cooked (and, to be frank, I only like the leaves and often de-stem them now that I make the dish more often). I had to struggle my way around getting both parts of the plant to cook correctly given their very different textures. There's a metaphor in there somewhere, but I'm too tired right now to find it.

In any case, sweet potato leaves aren't even available in much of the US as far as I'm aware, and I wasn't aware they were a vegetable that could be eaten until I moved here.

Partly, I just don't think Erway calls for adding enough oil. 2 tablespoons simply wasn't enough. Partly, though, it's that I know what well-made sweet potato leaves look and taste like, but I just did not grow up in a kitchen where they were frequently made. It's one of those ways in which, no matter how long I stay, I can't fully assimilate into the culture because I just didn't have that cultural upbringing. If I'd grown up around parents cooking this dish frequently, making it might be second nature, the way making hummus is for me.

I also prefer them with a dash of soy sauce instead of salt, although I don't think that's how they are typically made.

Damn it, white lady, screwing up our traditional foods with your weird changes!

But seeing as other recipes call for adding ginger or MSG, and this one doesn't, I don't feel too bad about that.

Oyster omelet (蚵仔煎)

|

| This was the best-looking oyster omelet I made. They all tasted good, though. |

This was probably the most interesting of the dishes I made - not just for the act of making it, but in my friends' reactions when I told them what I was attempting. In my experience, it just isn't one of those foods that's made at home very often (which is also interesting - as it's not any harder than any other omelet). I've asked and asked, and not found a Taiwanese friend who has actually made this themselves. It's always something you get as a snack when you eat out.

But here I am, making it in my kitchen even though nobody else I know does that. I feel like it almost makes me

more foreign. I'm not even sure what the equivalent would be - a Taiwanese person who goes to the US and tries to make a Big Mac in her home kitchen? ("For a truly authentic Big Mac, you have to start with a patty that is just the right shade of grey.")

The first thing you do when you make this is prepare the sauce. In fact, I wonder how 'traditional' the sauce even is, seeing as the base is ketchup. But it works - it is a bit tangier than the typical sauce you get in the night market but very good.

The only real issues I had were that the bok choy didn't cook as well as I would have liked - I found that putting it in the oil just as the oysters are shrinking a bit, just before adding the sweet potato starch mixture, works well.

My oyster omelets all tasted good but looked like garbage. That's fine - my Western-style omelets are the same.

Chicken rice (雞肉飯)

|

| I used pre-slivered chicken - probably better to shred it post-cooking instead. It was a bit dry, easy to overcook |

This was one of those recipes with a head-scratcher of an extra ingredient - Sichuan peppercorn powder?

Huh?

I decided that I was going to break my rule of following the recipes faithfully at least the first time, and omit this. I accept it is a possibly acceptable "variation", but I have never, ever eaten chicken rice that tasted like it had anything like Sichuan flower pepper in it, and a Taiwanese friend I mentioned it to just raised his eyebrows and had...no words. But go ahead, try it, why not. I thought it tasted pretty authentic without it.

What I also found odd was that Erways' recipe calls for putting the fried shallots on top of the chicken, but it seems clear to me that they're meant to go in the sauce, where they turn into soft goober things that stick to the rice and chicken and make it tasty. I've never had chicken rice with crispy fried shallots, only soft goobered fried shallots.

Reader, I goobered my shallots.

Erway calls for steaming the chicken, other recipes call for boiling it. I think either is fine.

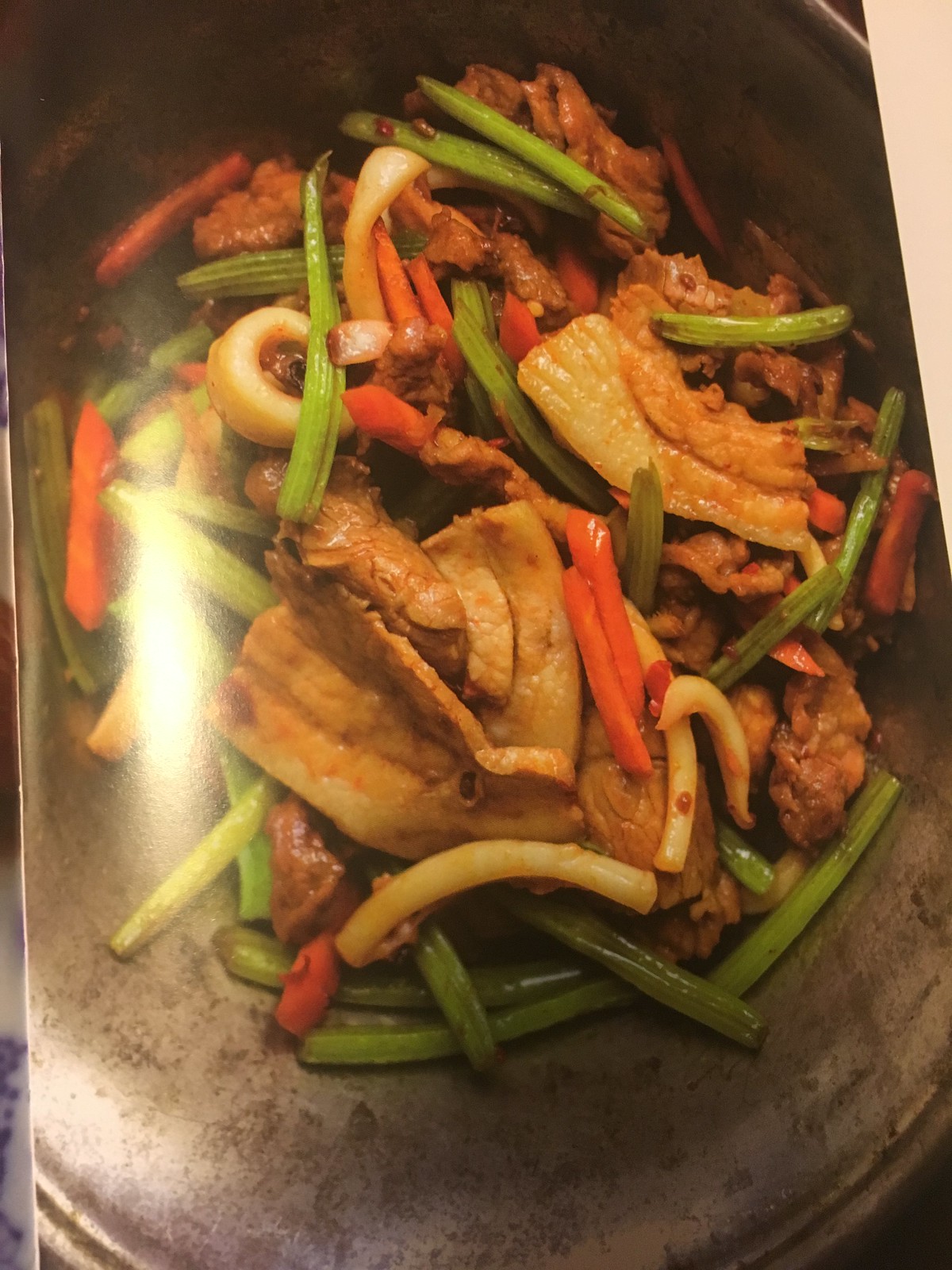

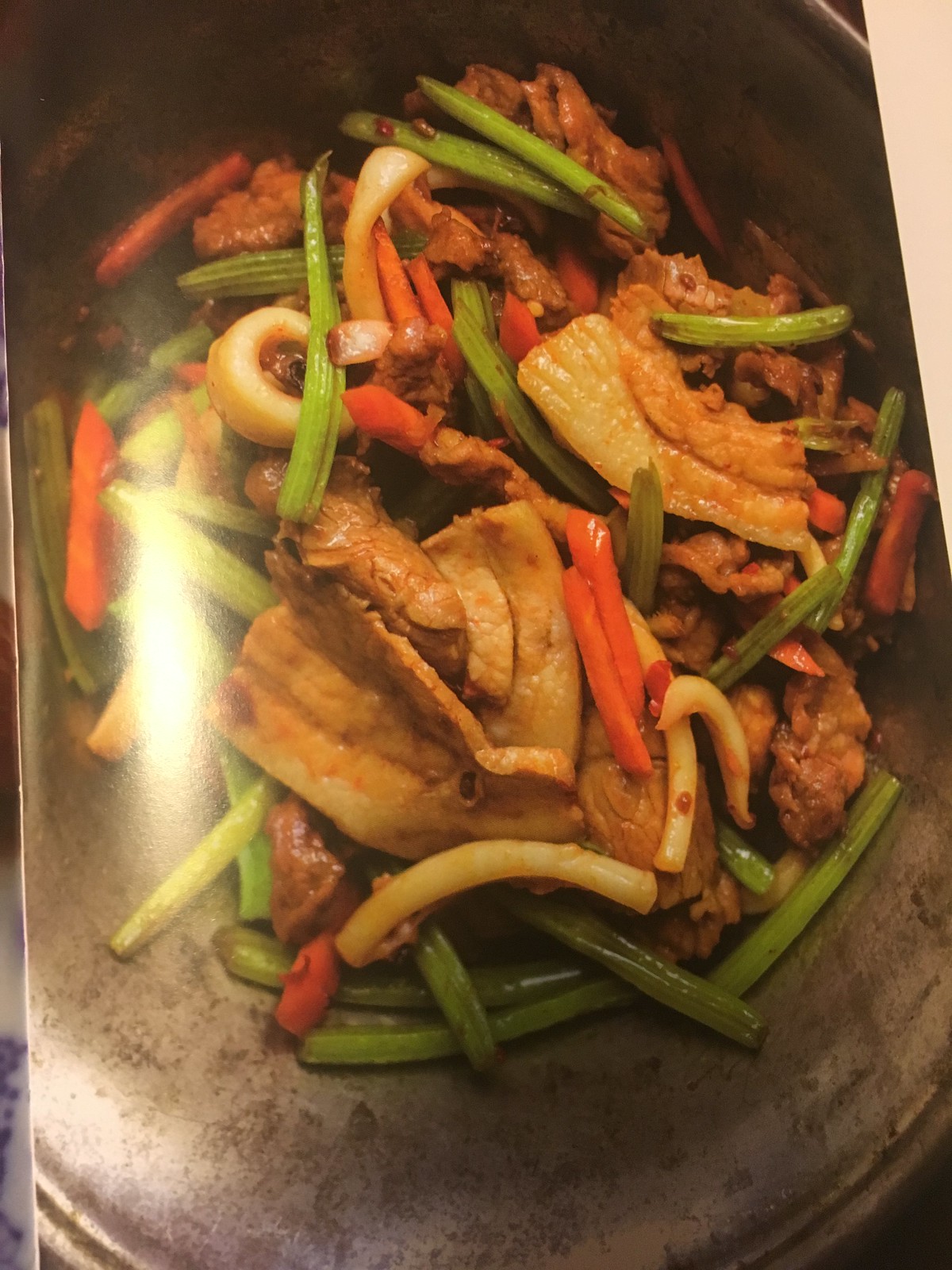

Hakka stir-fry (客家小炒)

|

| Could use more color |

This was the recipe that I had to throw out. It forever has a black mark - it's not so much that it doesn't work as that the result

does not look or taste anything like Hakka stir-fry.

Granted, "Hakka stir fry" has a lot of individual variation: even the name is fairly generic. It's like saying "New York Pizza". A very definite thing, but Giulio's, Mario's, Matteo's, Tony's and everyone else's are going to all have their own way of doing it. A Grimaldi's slice isn't quite the same as a typical Staten Island slice. So it goes with Hakka stir fry. Some varieties being fairly healthy-looking (they're not - they're full of sugar and oil) and others being...not that. Some involve dried tofu, others do not. Some include scallions, others do not. But all Hakka stir fries have a few things in common:

- They use strips/slivers of pork, not sliced

- They all include soaked dried squid, not fresh

- They all include garlic bolt/garlic green and Chinese celery

- They all involve some combination of garlic, rice wine or other alcohol and soy sauce, and some form of chili

- NONE OF THEM HAVE CARROT IN THEM

Erway's recipe called for fresh squid (!), larger sliced pieces of pork, according to the picture (!!), no garlic bolt (!!!), no dried tofu (okay - I know Hakka people who don't include it), and...carrot (!!!!).

I wanted this to be just another acceptable "variation" on a classic, or to find out that I'm just a dumb whitey who has no business telling Cathy Erway - who is of Taiwanese heritage - how a Taiwanese dish is made. But it isn't and I think maybe I'm not. I posted about it on Facebook, and got, from a variety of Hakka people, people who asked Hakka people and people married to Hakka people, some variant of:

"No!"

"HELL NO"

"Absolutely not"

"THERE IS NO CARROT IN HAKKA STIR-FRY!!!"

"As a Hakka man who is over 30 years old, I have never had carrot in a Hakka stir fry"

"I asked my (Hakka, with parents who run a Hakka restaurant in Miaoli) wife and she says there is absolutely no carrot in Hakka stir fry and the meat should never be sliced like that."

"I asked my Hakka coworker and he just stared at me before saying "...no."

"Where is the dried tofu?"

So, "acceptable variation aside", I can only conclude that Erway just - didn't include an accurate recipe for Hakka stir-fry. There are limits to what constitutes acceptable variation, and the Hakka People Of Taiwan Whom I Know have spoken: this recipe crosses a line.

I have to wonder if Erway just doesn't know Hakka food - her recipe for "citrus sauce" sounds like Hakka kumquat sauce, but...uses orange juice? That's odd. Either make it with kumquats or don't make it at all.

I chucked the whole thing, cobbled together a few recipes online, soaked my dried squid (easier to do than you'd think but start well ahead of time, and be aware that it stinks up your kitchen - and use rice wine or shaoxing wine, maybe with water to create enough liquid to soak a whole dried squid) and came up with a pretty tasty, though perhaps slightly pallid-looking, stir-fry.

|

| But this just...doesn''t look like Hakka stir-fry. I'm sorry. (Photo from The Food of Taiwan) |

Erway suggests chili bean sauce (again with the chili bean sauce) rather than the sliced red chilis others call for, but she may be on to something here. Hakka stir fry I've had outside is redder/more colorful than what I came out with, and chili bean sauce might help with that.

* * *

So there you have it. The good, the slightly odd, and the unacceptable of

The Food of Taiwan. I'll leave you with this thought: it seemed odd that it included a bunch of dishes I'm not really that familiar with - though maybe that's just because I don't order them often - but left out two of my favorites, which I would have thought would have made the final cut of any Taiwanese cookbook: scallion pancake (蔥油餅) and cold eggplant (涼拌茄子). I haven't made scallion pancake, but I did make cold eggplant, and it turned out great:

|

| Why wasn't this in the cookbook? Two other eggplant dishes were. |

I used

this recipe, but added a little cilantro at the end, put some thick soy sauce in the mix to make it stick to the eggplants better, drizzled some thick soy on them after setting them on the plate, and actually steamed rather than boiled them. They smell so good when they are steaming.

Happy cooking!

And please feel free to leave your own cooking experiences with Taiwanese food - or any tips, hints or suggestions you have - in the comments. I'm always looking to improve my craft.