|

| This is what I'd like to do to the hands of everyone who types the word "mainland" - I mean metaphorically...of course |

So, I don't feel like writing about Terry Gou deciding not to run for president because reasons. I want to write about how the international media have taken Hong Kong off the front pages just as the Hong Kong government and their

Instead, I want to write about a thing someone messaged me about recently - hadn't I written something once about the use of the word "Mainland"? I thought I had, but other than a section in this piece, I can't find it. So - great. Let's do that now.

I'm going to take what I wrote there and expand it here.

Let me begin this first part by saying that I am not an expert on Cyprus. But, if one day I opened up the New York Times and saw an article about Cyprus with a sentence like "Cyprus just [did a thing that any normal sovereign nation would do], which drew a strong reaction from Mainland Turkey", my eyebrows might get stuck to the ceiling. The paper would almost certainly receive a flood of angry mail from indignant Cypriots and those who sympathize with them, and would probably be compelled to chastise the reporter or editor as well as issue a correction briefly explaining the true situation.

Or imagine if someone wrote about "Okinawa" and "Mainland China" (after all, China does claim Okinawa) - the reaction would be stunned, at best. In fact, Japan took the Ryukyus not long before it took Taiwan, there is some ancient history between the Ryukyus and China (not that it should matter), the US occupied the islands for decades after WWII and only gave them to Japan in the 1970s, and there is an independence movement there. And yet you'd never say "Okinawa and Mainland China" just because China might want you to.

So why is it so acceptable to use "Mainland" when referring to China in relation to Taiwan? Why do people think they can use that term apolitically? It is clearly not a neutral word.

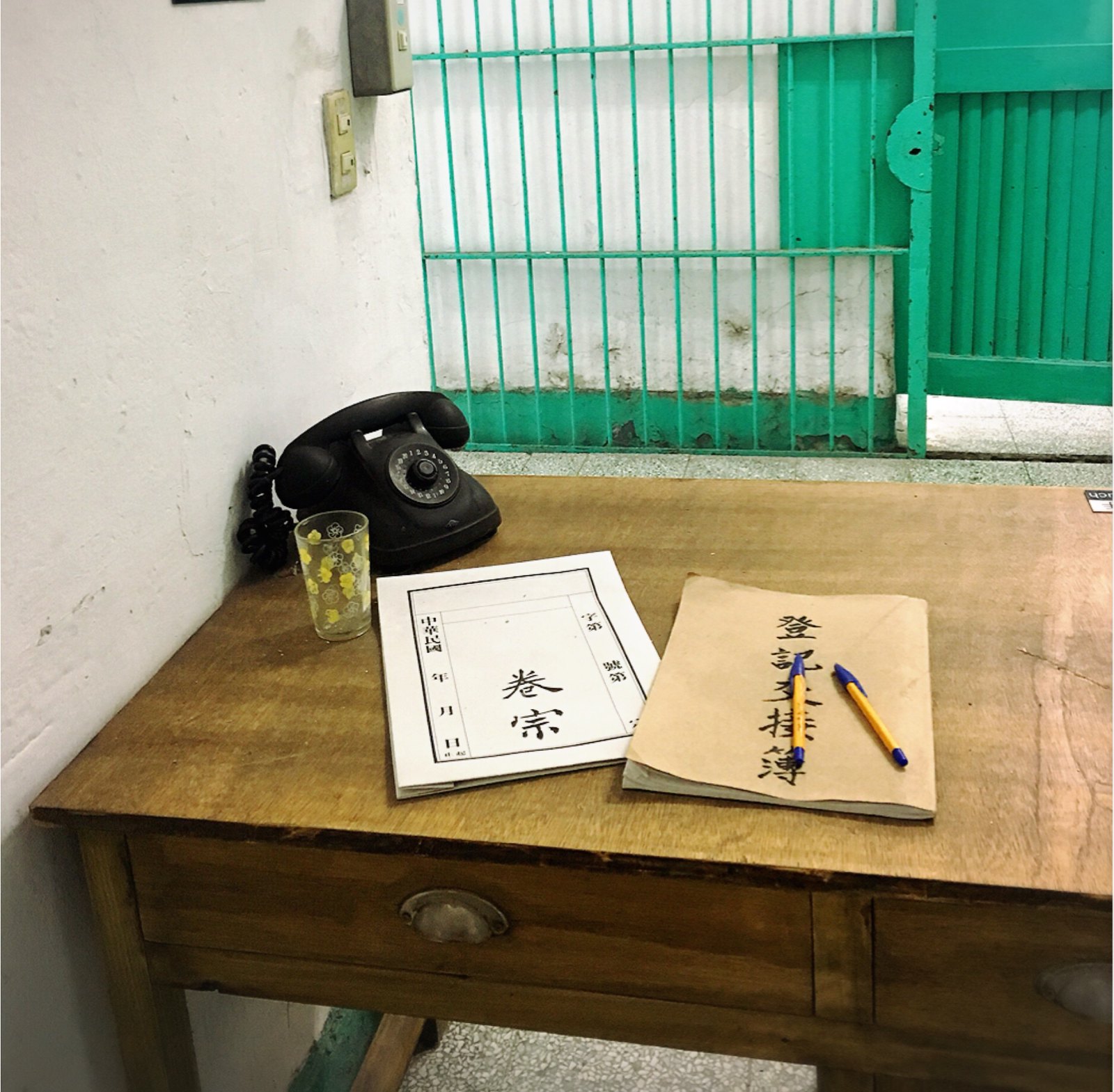

Here is what it means, specifically:

The clear connotation of “mainland” is that it is the main/continental part of a territory, and that outlying islands which are referred to in relation to it are also part of said territory.

By that metric, the only reason to use the phrase “Mainland China” in relation to Taiwan is if you want to imply that China and Taiwan have some sort of territorial relationship, or that Taiwan is a part of some larger concept of China. If you believe they are two sovereign or at least self-ruled entities, it makes no sense at all. In that sense, Taiwan does not have a mainland, unless you want to refer to “mainland Asia” (as Taiwan is a part of Asia, but not a part of the People's Republic of China).

Why then do people keep saying it? Partly it is force of habit. Pro-China types insist on it, and the media often follows. It is unclear how people came to believe the word was neutral or apolitical. It is not. It implies that there not only is but also should be a territorial relationship.

Even if you want to claim that, because the ROC officially calls itself 'China', it's acceptable to call the PRC "mainland China", I'd still challenge you on that. The ROC came to Taiwan from China and occupied it at the behest of the Allies in 1945 (there is no binding treaty that definitively cedes Taiwan to any government of "China"). Regardless, that government was not invited here by the Taiwanese people. They were never asked whether they wanted to be a part of the ROC, most don't identify primarily as Chinese now, and most don't support any sort of unification. If it could be done without any threat of 'retaliation' from China, the ROC would quite likely - though not definitely - be on its way out by now, if not entirely gone in favor of a Republic of Taiwan. Most Taiwanese refer to their home and country as Taiwan, not "the ROC".

If you refer to the island that people who don't identify as Chinese as something off the coast of "mainland China" (implying a territorial relationship they never agreed to), is that much different from telling people how they must identify? Are you not telling them "you think of these islands as your home country, but it's actually a piece of territory connected to a larger 'mainland', whether you like it or not"?

Some might say that omitting the word "mainland" and just using "China" and "Taiwan" is overtly nationalistic. But it isn't - it's just stating the truth as it is now. Taiwan exists, and it's not part of the country commonly referred to as "China", which as of right now is the People's Republic. It's the name of an island, and it's also what almost 24 million people call their country. It's not nationalistic to refer to a place people consider a country as a country, and a different place that they don't consider part of their country without any qualifying markers implying that it might be otherwise. Right now, there's a country called "China", and there's an island, which you can also call a country, called "Taiwan" with a different government than the one in "China". How is it 'nationalistic' to just say so? How is it not nationalistic to draw specific kind of connection between Taiwan and China by calling one the "mainland" of the other?

Simply using "China" and "Taiwan" is also the most open way to refer to these two places without closing off any future possibilities. "Mainland" implies that there ought to be some kind of future relationship in which the two places are connected. "China" and "Taiwan" are two existing places whose statuses may change in the future - referring to them as such doesn't cut off any potential outcomes. "Taiwan" and "Mainland China", however, does: it neuters the notion of Taiwanese independence in the present, by giving Taiwan a "mainland" that the Taiwanese never asked for.

How political is “mainland”? It is required as a corresponding term to “Taiwan” in Xinhua’s style guide, a reflection of Chinese government policy. When you use it, you are quite literally referring to Taiwan-China relations exactly as the CCP wants you to. If you want to talk about Taiwan exactly the way the Chinese government prefers, by all means use “mainland”. But why would you?

Think of it this way: you may not necessarily default to Taiwanese independence as the only possible future for Taiwan. You may think the ROC is legitimate. I don't agree with you, but fine. These are valid (if flawed) opinions. Great news! You can still believe those things while calling China "China" and calling Taiwan "Taiwan", because a place exists called China, and another place exists called Taiwan! That terminology has room for your views while also making room for opinions which disagree with yours, whereas "Mainland China" does not.

I know what you're thinking. But acktchuelly, you want to say, Taiwan's situation is diffrennnt than Cyprus or Okinawa! Yeah, sure, it is. Taiwan is in a unique position. But I do think they are comparable enough for this purpose: saying Turkey is the "mainland" of Cyprus makes a political statement about who you think should ultimately govern Cyprus: and unlike the PRC in Taiwan, Turkey actually already occupies part of that island. Saying "Taiwan and mainland China" similarly makes a political statement, implying that some government of China which includes the current China would be a more legitimate government than an autonomous, mainland-free Taiwan.

And sure, nobody reasonable disputes that Okinawa is, at least currently, Japanese territory. But then nobody reasonably thinks that Taiwan should be a part of the PRC, and nobody reasonably thinks that the ROC is going to "defeat the communists and take back the mainland". And the PRC has about as much right to claim Taiwan as it does to claim Okinawa - and they try to use historical arguments to justify both, even though the current government of China has never controlled either. And as far as I'm aware, just like the Taiwanese, neither the Cypriots nor the Okinawans want to be a part of Turkey or China, respectively.

So why would we all instinctively consider the use of "mainland" to be offensive in those situations or at least to be making political judgement calls we have no right to make, but not in the case of Taiwan? Is it a good idea to keep using the exact terminology that China wants us to use? Do we really want to keep being useful idiots?