"Բարեւ Ձեզ սիրելի կամավորներ: Շատ ուրախ եմ նսրից հանդիպել ձեզ," Anna says. She goes by Anna, not Dr. Sahakyan.

I understand and nod. I'm not a volunteer, not in Peace Corps, and not in Armenia, but the language course videos are online, so why not?

"Այսօր մենք սովորելումենք ինչպես հարցնել ճանապարհը:"

Now I freak out -- I don't understand this at all. The first twelve videos were introduced in English, but the actual volunteers learning Armenian with Anna have materials and live online sessions, which I do not have. I suppose by the time they get to this point, their service has begun and they're far ahead of me. I figure out what she just said using logic, educated guesses, an Armenian keyboard and Google Translate.

At least my pronunciation seems fine, because I'm able to recall and imitate what my grandfather's generation sounded like when they met for the holidays and had throaty, velar conversations from which I was completely excluded. But I don't really know. There's no one to check if my ը is schwa-y enough or my խ sufficiently tubercular.

The video ends and I set a reminder to transfer my messy notes to the neater record I keep. I reach to the right and grab my Taiwanese textbook. We've had a few lessons, all of which have focused on mastering pronunciation. I expected the tones to be difficult, but they're not (yet). It reminds me of all the musical training I'd otherwise forgotten, and anyway it's a similar principle to Mandarin, just...more of it, and harder.

The video ends and I set a reminder to transfer my messy notes to the neater record I keep. I reach to the right and grab my Taiwanese textbook. We've had a few lessons, all of which have focused on mastering pronunciation. I expected the tones to be difficult, but they're not (yet). It reminds me of all the musical training I'd otherwise forgotten, and anyway it's a similar principle to Mandarin, just...more of it, and harder.

It's the the k and g that get me: I can't hear the difference, so each is inconsistently produced. haven't learned a single actual word that I can remember, but I dutifully listen to the recordings and parrot along. Someone's going to check, and Ms. Deng has struck me as rather meticulous.

Both methods are strikingly Audiolingual. Armenian has to be; how else does one deliver asynchronous online sessions? You can't teach communicatively without someone to communicate with. For Taiwanese, I suspect it's partly based on how Mandarin is taught (that is, very traditionally), and partly because most of Ms. Deng's students are hopelessly Indo-European: they need and expect the pronunciation support. I'm told by a friend who also takes lessons that she'll be happy to practice speaking authentically once I'm able to speak at all.

Still, Armenian starts with conversation: Hello, how are you? I'm fine, you? I'm fine, thanks. What's your name? My name is Anna. And you? I'm a teacher. I'm a volunteer. Communicative methods aren't embedded in Armenian; they went through centuries of inefficient teaching and learning modalities just like everyone else. The method is Anna's doing.

Armenian also has something called the trchnakir, a Medieval illustrator's avian dream, in which the letters of the alphabet are rendered as brightly sinuous bird bodies. I know the difference in learning style has nothing to do with that, but there's something poetic in thinking of one of your new languages as music, practiced like I quacked those first notes on a trumpet years ago. I had to learn to read music, of course, before I could do much of anything. It was months before I played a real song. The other is the organized chaos of a watch of nightingales, a murmuration of starlings or a charm of finches. You just up and go.

Both methods are strikingly Audiolingual. Armenian has to be; how else does one deliver asynchronous online sessions? You can't teach communicatively without someone to communicate with. For Taiwanese, I suspect it's partly based on how Mandarin is taught (that is, very traditionally), and partly because most of Ms. Deng's students are hopelessly Indo-European: they need and expect the pronunciation support. I'm told by a friend who also takes lessons that she'll be happy to practice speaking authentically once I'm able to speak at all.

Still, Armenian starts with conversation: Hello, how are you? I'm fine, you? I'm fine, thanks. What's your name? My name is Anna. And you? I'm a teacher. I'm a volunteer. Communicative methods aren't embedded in Armenian; they went through centuries of inefficient teaching and learning modalities just like everyone else. The method is Anna's doing.

Armenian also has something called the trchnakir, a Medieval illustrator's avian dream, in which the letters of the alphabet are rendered as brightly sinuous bird bodies. I know the difference in learning style has nothing to do with that, but there's something poetic in thinking of one of your new languages as music, practiced like I quacked those first notes on a trumpet years ago. I had to learn to read music, of course, before I could do much of anything. It was months before I played a real song. The other is the organized chaos of a watch of nightingales, a murmuration of starlings or a charm of finches. You just up and go.

(Originally from this tweet)

Taiwanese starts with a, á, à, ah, â, ā, å (I made that last one up; my keyboard won't type the actual diacritic). Do all that, then you can have some words. We go over it again, and yet again, until Ms. Deng is satisfied with my ability to stumble around in her language.

"Okay!" she says.

"Okay," I laugh. Just okay.

Okay, but why am I doing this? Do I enjoy elaborate constructions of linguistic masochism? (A little, yes.) Why both? Why now? Why these two hilariously unrelated languages? At the same time?

One is about the past, one is about the future, and in both, I'm a pretender. I speak neither language yet, though I can make sounds which imply I kind of do. Generously, I am a small child in the body of an adult, whose tongue can thrash around like a baby: goo-goo gaa-gaa barev dzez, inchpes ek, shnorakalutiun yev hajogutsyun Զեփյուռ կդառնամ, մեղմիկ աննման: Սարերից կիջնեմ, նստեմ քո դռան. Cháu chháu kâu gâu pōng bōng ng hng ióng hióng 在這個安靜的暗暝, 我知道你有心事睏袂去, 想到你的過去, 受盡凌遲, 甘苦很多年。

Neither my Armenian nor my Taiwanese is that good, but I understand those lyrics. One of the ways I bolster my motivation is to listen to music I like in languages I'm studying. I look up what is being said, even if I'm not ready to truly learn it yet.

Neither my Armenian nor my Taiwanese is that good, but I understand those lyrics. One of the ways I bolster my motivation is to listen to music I like in languages I'm studying. I look up what is being said, even if I'm not ready to truly learn it yet.

I chose Armenian because I simply felt I had to. For too long, I've acted like a victim of the heritage language denied me, all those ideas and modes of expression that nobody thought important enough to pass on, a cold wall between all those relatives who thought their opinions, ideas and perspectives didn't matter enough for me to understand them. My great-grandmother died when I was 14, and while we had real conversations, I can't say we ever had full, deep, real ones. I both knew her and didn't.

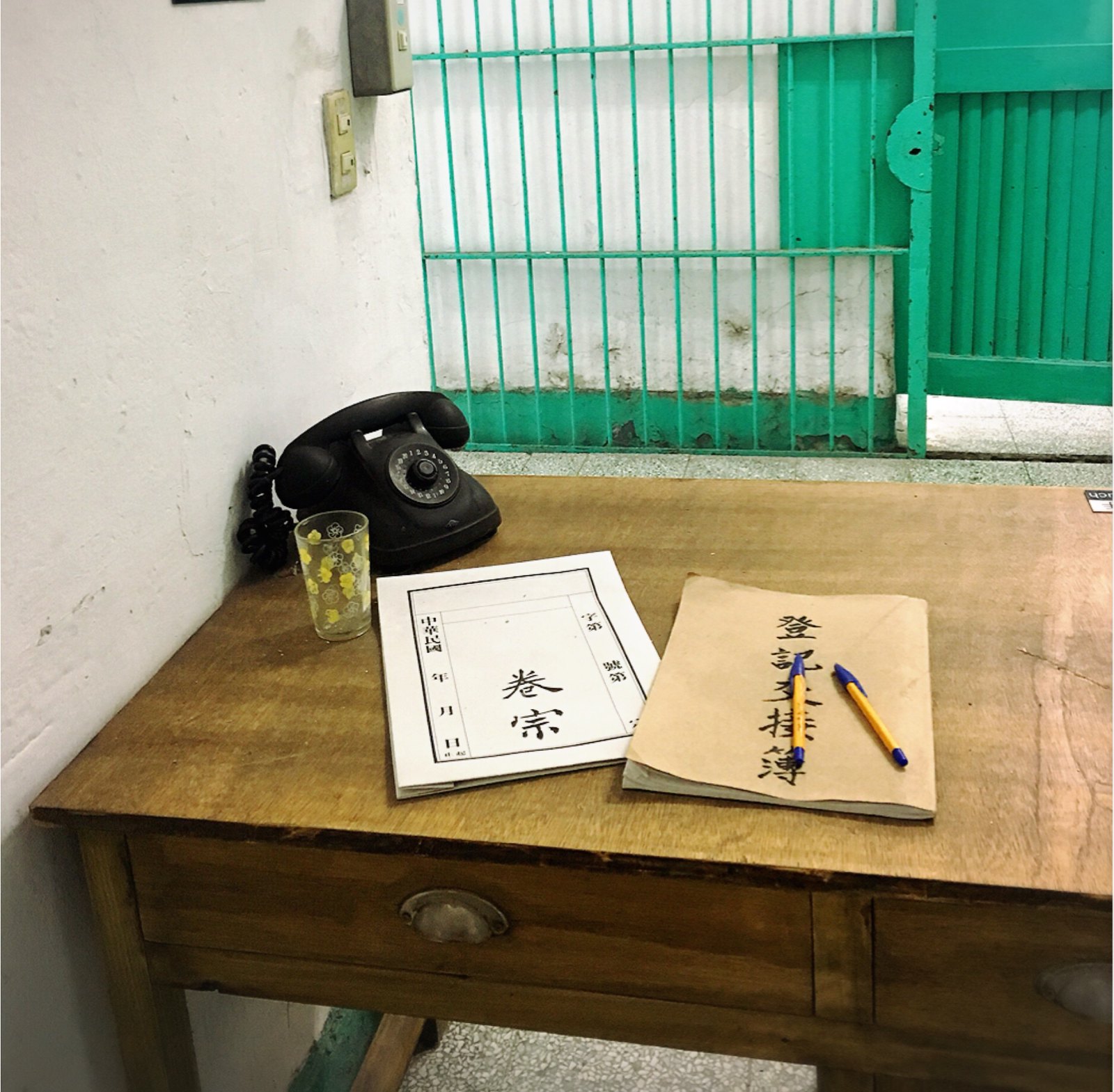

This memory resurfaces every time a Taiwanese acquaintance reveals that they could barely communicate with their own grandparents because their generation was raised in Mandarin but their elders barely spoke it.

Being a linguistic victim sucks, though, and it doesn't even suck in an interesting way. I'm unlikely to ever be fluent, but if I can have an understanding and some basic Armenian conversational skills, it'll be a victory. Just because my grandfather made a decision in 1953 doesn't mean I have to abide by it. I think it's necessary not just to connect with my heritage, but to move my own story forward as well. As far as I know, I'm the only Renjilian of my generation who decided to re-learn, however imperfectly, what was lost.

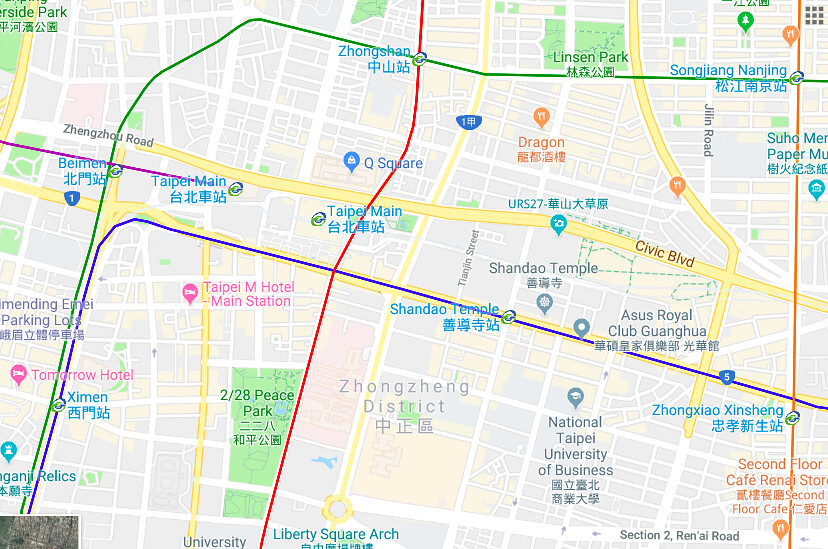

I have no such ancestral connection to Taiwanese. I moved here at the age of 26 for no specific reason: it just looked like an interesting place to be. I stay for a thousand reasons, which deserve their own post. Whatever connections grow from learning this language, they are entirely in the future. I don't know that I'm trying to prove that Taiwan is actually my home now...except perhaps, I am.

Still, I feel like a fake. My family spoke Western Armenian (the last native speaker died just this summer). I'm learning Eastern, because that's what's available. As for Taiwan, well, I consider this my home but I'll always be seen as something of an outsider, no matter what language I learn.

It turns out that both Armenian -- especially Western Armenian -- and Taiwanese are somewhat inaccessible; both suffer from a dearth of teachers and materials. There are days when I have to tamp down annoyance that I have to work for a heritage language I should already know, and a local language I began learning about 15 years too late.

That's a long time to put something off, so I felt a strong need to start now. Not in a year, not after I'd gotten some Armenian under my belt, and not until I could improve my Mandarin (as I used to tell myself). Now. If I wait too long, I'll wait forever.

It turns out that both Armenian -- especially Western Armenian -- and Taiwanese are somewhat inaccessible; both suffer from a dearth of teachers and materials. There are days when I have to tamp down annoyance that I have to work for a heritage language I should already know, and a local language I began learning about 15 years too late.

That's a long time to put something off, so I felt a strong need to start now. Not in a year, not after I'd gotten some Armenian under my belt, and not until I could improve my Mandarin (as I used to tell myself). Now. If I wait too long, I'll wait forever.

The inaccessibility is a bit seductive, though. Many have the opportunity to learn Mandarin. Who is so lucky as to have an experienced Taiwanese teacher dropped in their lap by recommendation? I have to learn it via Mandarin, which frankly provides more motivation to improve said Mandarin than I've felt in years.

Armenian is the same: most Armenians speak Russian as a second language, and the diaspora all have other tongues now. Russian is more common as an offering -- how many have the patience to practice Armenian from Taiwan, with no feedback and no real reward? I'd be surprised if there were six Armenian speakers in the whole country!

Both languages need more speakers: Taiwanese was the target of an intentional campaign of eradication, and even today is insultingly classified as a dialect despite being mutually unintelligible with Mandarin. Unsurprisingly, Taiwanese is an endangered language. Western Armenian is endangered as well, and I'm unlikely to be able to access it unless I learn Eastern Armenian first.

Neither language is widely considered useful: I've already been advised to just stick with Mandarin -- or worse, to spend my time practicing Simplified characters. I blanch at the thought! I've also been told to just learn Russian as I'll get more utility out of it.

That's just fuel, though. I'm sick of the utilitarian argument. It's a privilege to be able to float around in languages that aren't international, that you don't need for anything in particular. But it's also what draws me.

Maybe I have something to prove or I just like learning "useless" things, but I'm not doing this for utility. My intrinsic motivation to learn Mandarin died awhile ago; I persevered because it was useful. I was never a huge fan of the politics of it. Yes, Taiwanese has a settler-colonial history too, but it should have never been suppressed the way that it was. In any case, most expats come to Taiwan expecting to learn some Mandarin. Some succeed, some don't. How many come and decide to learn Taiwanese?

I know more than one, but there could be -- should be -- even more than that.

As for Western Armenian, it should still be widely spoken across Anatolia. But it isn't. You know why.

With opinions like that on why languages are worth learning, who needs usefulness?

And yet, blue eyes in Armenian culture portend bad luck -- they're said to be more susceptible to the effects of the evil eye (I think this is why charms against the evil eye across the Mediterranean are blue). Yeghishe Charents even wrote of it -- Blue-Eyed Armenia. And here I am, a blue-eyed white lady learning two wildly disparate languages and wondering what bad luck might await.

The worst possible outcome is that I make a short study of both, learn neither well, and they enter the dormant part of my brain where French and Spanish are buried. Just another person who "took a language class" but never actually learned the language. Or I'll try and try but never master tone changes in Taiwanese, and always be stuck sounding like a tortured goose. Or I'll go to Armenia again, someday when it's safe, and proudly try out whatever Armenian skills I've gained by then only to be laughed at because my pronunciation sounds more like a series of sneezes than comprehensible language.

I also wonder, given the endangered status of both languages, if I'm actually helping by being a new person -- something of an outsider -- interested in learning. Or am I just rubbernecking as both languages fall, like birds shot out of the sky by the KMT, or the Young Turks?

As China amps up its provocation and bullying of Taiwan and Armenia stands on the precipice of invasion by Azerbaijan, am I doing anything meaningful by learning Armenian and Taiwanese? It strikes me as a statement: I will help preserve what you are trying to destroy. But am I really helping, or indulging myself? I can't help but think it's closer to the latter.

And yet, I keep practicing pronunciation until Ms. Deng moves us on to actual words. When I feel I've done enough, I head over to Youtube. Anna's classes are a challenge now, but if I'm tired I can always watch Bopo children's television and learn colors, or animals, or whatever.

Perhaps I'll never succeed at either language. Perhaps Armenian won't lead to whatever window on the past I'm looking for. Certainly, learning Taiwanese won't make me a local. Neither language will lead to a better job, more money or even many conversation partners. But it's worth it.