|

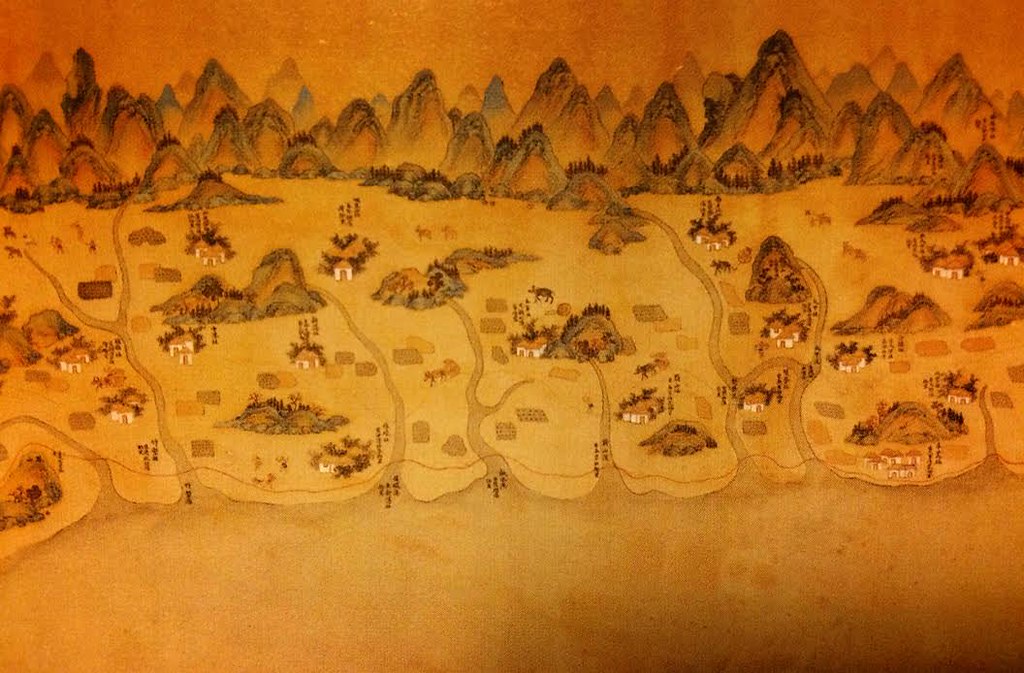

| Qing-era map of Taiwan, coastal view. From Jerome Keating's The Mapping of Taiwan (I literally just took a photo of the page) |

I'm not sure what to make of The Stolen Bicycle, and I suspect that's exactly how Wu Ming-yi intended it.

I mean, I'm not even sure if the story follows linear time or not. The basic plot - the unnamed youngest son of a family whose father disappeared thinks he might be able to find his father if he can find the bicycle that went missing with him - does have something of a timeline. Nothing else does, nor is it meant to: because memories both individual and collective simply don't do that. That's what they are - scattered memories of scattered people, sometimes sharing with each other. To call them flashbacks would be reductive.

The thing is, not only does he find the bicycle fairly early on in the narrative - meaning that the story put forward in the synopsis is not the story at all, but the bicycle hadn't been stolen. His father had taken it when he left. And he had known that when he set out. Of course, that's the point. There are other stories: break-ups that lovers never quite get over, the story of elephants at the old Japanese zoo near Yuanshan and their march from Burma, a war photographer's ride down the Malayan peninsula on an old Japanese military bike. Past stories of stolen bicycles, at least one of which returned. Some stories conclude, some don't. People die or are damaged, some beyond repair. Others can be refurbished. The characters trudge on.

So what is the point? I don't think Wu intends to tell us: we are meant to meditate on this almost scrap-book like collection of memories, like journal entries, interspersed with notes on the history of bicycling and zoo animals and World War II in Taiwan, along with the occasional diagram. Like Shizuko's three-dimensional side-perspective map of the Taipei Zoo, you're not meant to see it as a treasure map to X or as a plot from a bird's eye view, but as though you are flying past it on a helicopter (or maybe approaching it from the Maokong gondola, which is explicitly referenced as not having been built yet when the map in question was drawn).

Or like those old maps of the Taiwan coast, that show the shore from the perspective they'd have approached it, from the beach back to the mountains which create the spiky horizon past which nothing can be seen.

I don't mean to imply that the book has no themes - although I've just spent several paragraphs waffling about without saying what they are. There is discussion of how lives, just like bicycles (or elephants) wear out with use: and those bicycles are like our beasts of burden. Some parts get rusty, others jammed, others fall apart, some parts need replacing. Some bicycles - like lives - completely crap out and are scrapped. Others, with tender care, can be refurbished. In Taiwan, the local bicycle industry started out by importing from Japan, then imitating it, then creating its own models.

There are butterflies - a fictionalized memory within a memory - linked to Taiwan's handicraft history (though I have never seen a "butterfly wing collage" myself). The more butterfly lives that are sacrificed, the more beautiful the result.

And there is World War II: a lot of lives were sacrificed in that. Was the result, when it comes to Taiwan, beautiful?

I don't know how else to describe The Stolen Bicycle except in these scraps of thought, and I'm leaving a lot out (I still don't understand the scene that was either in a flooded basement or the bottom of a river, nor the relationship between fine craftsmanship and wild jungle animals - though I am sure there is one). I can't imagine it was meant to be any other way.

So if this review is a bit weird, forgive me. The book is a bit weird too.

I liked it, though. It rattles around in your head after reading, like a very long Zen koan. It's not meant to make perfect logical sense, I guess. It's Taiwan from a littoral view. It seems intent on pushing you to think in paradoxes, to reach a point where you can intuitively grasp an answer that is logically impossible.

No comments:

Post a Comment