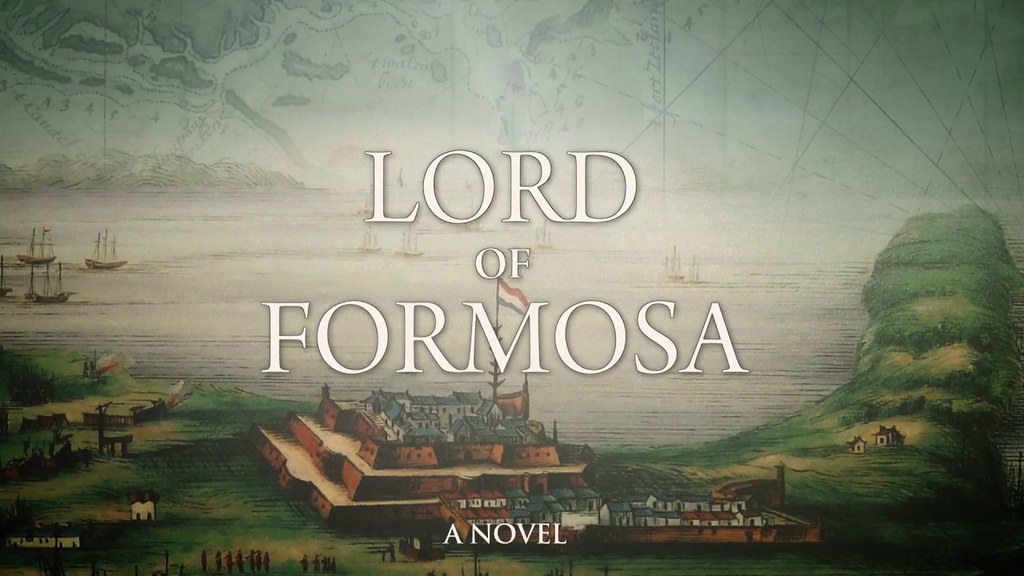

It is a pleasure for a work of historical fiction to come out on an area of history I am particularly interested in (Taiwan, obviously). It is an even greater pleasure when that work of historical fiction is not only engaging, but generally accurate. Joyce Bergvelt's Lord of Formosa has earned both of these adjectives.

Lord of Formosa is essentially a biography of Koxinga (國姓爺 or 鄭成功), the 17th-century scholar/pirate/businessman/military leader/talented crazy dude, from his early life on the Japanese island of Hirado (off Nagasaki) with his Japanese mother, Tagawa Matsu to his upbringing at his father Zheng Zhilong's (鄭芝龍) estate in Fujian, followed by his rise as one of the most talented loyalist military leaders resisting the encroaching Manchu (Qing) conquerers to his conquest of the Dutch colony on Taiwan. It's interspersed with viewpoint chapters from the Dutch colonial officers as well as Koxinga's parents.

It tells the story, in short, of a man given the Imperial Surname (國姓爺) by a dying empire, a man given the title 'Success' (成功) who was, in the end, not all that successful.

The story itself is somewhat tragic: Koxinga fulfills what the novel depicts as his 'destiny' but pays for it dearly. He has to choose between remaining loyal to the collapsing Ming dynasty or to his father, and watches the devastation of his family at the hands of the Qing.

"He literally died of a broken heart," an acquaintance of mine noted.

But no, to hear historians tell it, he probably died of syphilis.

In this way, the thick novel is cinematic in scope, at times reading like a biopic. It would make an excellent film, and I can only hope someone will pick up the rights and do just that (as long as it's not a Chinese company hoping to use it as a propaganda vehicle for their government's aggressive territorial expansionism).

From the beginning, I was interested in how accurate Lord of Formosa really was. So, just after reading it, I picked up Tonio Andrade's Lost Colony, figuring it would be a good nonfiction counterpoint. I'm partway through that book now, and am surprised more by how much is accurate than the small details which are spun with more artistic license.

However, this isn't even the highlight of the book: the best part is simply how much fun it is to read. Despite being extremely busy, I read Lord of Formosa in three days, staying up late one evening to finish it. You know a book is good when it's 3am and you know you aren't going to get enough rest that night, but you just keep going because sleep won't happen anyway.

I also appreciated how forthright Bergvelt is with her characters' flaws. Zheng Zhilong is, to be frank, a total douchehole both in terms of his defection to the Qing and his treatment of his first wife. If his son Koxinga was any kind of hero, he was a deeply flawed one: often cruel and despotic, suffering from fits of uncontrollable rage which might have been brought about by the aforementioned syphilis. Of course, the syphilis would have been brought about by all the mostly-nonconsensual sex he was having.

What I'm trying to say is that Koxinga might have been brilliant, but he was also super rapey.

His regretting it later (in the novel's telling) doesn't change that. Oh, and like father, like son.

In fact, that Bergvelt successfully created a story that includes a variety of relevant, realistic female voices - not all of them kind, pure-hearted heroic martyrs - in a story and era that is so deeply, unrepentantly penis-driven (my masts are bigger than your masts - let us do naval warfare!) is a literary feat. While she could have done more with the housekeeper, Lady Yan and Koxinga's wife Cuiying, she does enough to show that behind every story of dueling dicks, there are women who also drive the plot. And yet, she doesn't shy away from exactly how those women are treated.

The Dutch, who are portrayed not entirely unsympathetically, still come across as stupid - not really understanding Asia or the goings-on in the colonies they ruled - as well as greedy and racist. This was historically accurate: they did consider Chinese men to be 'effeminate', not a fighting force that could vanquish their (smaller) military might. That's racist. They didn't care nearly as much about the welfare of the people on Formosa, be they indigenous or Hoklo, as they did their profits. This is not only historically accurate, but also racist.

On the other hand, Koxinga was kind of racist too - believing he had the right to take Taiwan because most residents by that time were Chinese (mostly brought over as laborers by the Dutch, who worked them like serfs) and therefore Taiwan ought to be a part of China, is just a different way to be racist. He didn't 'liberate' Taiwan from colonizers - he was just another kind of colonizer.

If I have any criticism of Lord of Formosa, it's that that point could have been made more forcefully.

Bergvelt takes a few artistic liberties. There was a fortune-teller in Japan who was more of a plot device than real character. I'm not sure how many of the Hoklo characters on Formosa were real people (though at least two - Guo Huai-yi and He [Ting]-bin certainly are). It is not clear how Tagawa Matsu died, although Bergvelt's telling of it is plausible, or even likely. Koxinga is depicted as growing less rapey over time (but still, again, super rapey) due to the effect his mother's death has on him. I'm not sure this would have played out in quite that way in real life - more likely, he was incapable of comprehending that the sex he unilaterally decided to have with women who didn't resist per se but also didn't consent is just as rapey as what Qing soldiers were doing. In other words, he didn't stop being rapey - he was just another kind of rapist.

That said, Bergvelt is a talented writer, understanding seemingly innately where to hew to historical accuracy and where to apply a bit of soft focus or streamlining. The story moves forward when it needs to (although I would have liked to have seen more of Koxinga's childhood in China) and lingers where it needs to.

Whether you are into historical fiction, want an engaging read of a period of Taiwanese history in particular, or just like a good novel, I strongly recommend it.