|

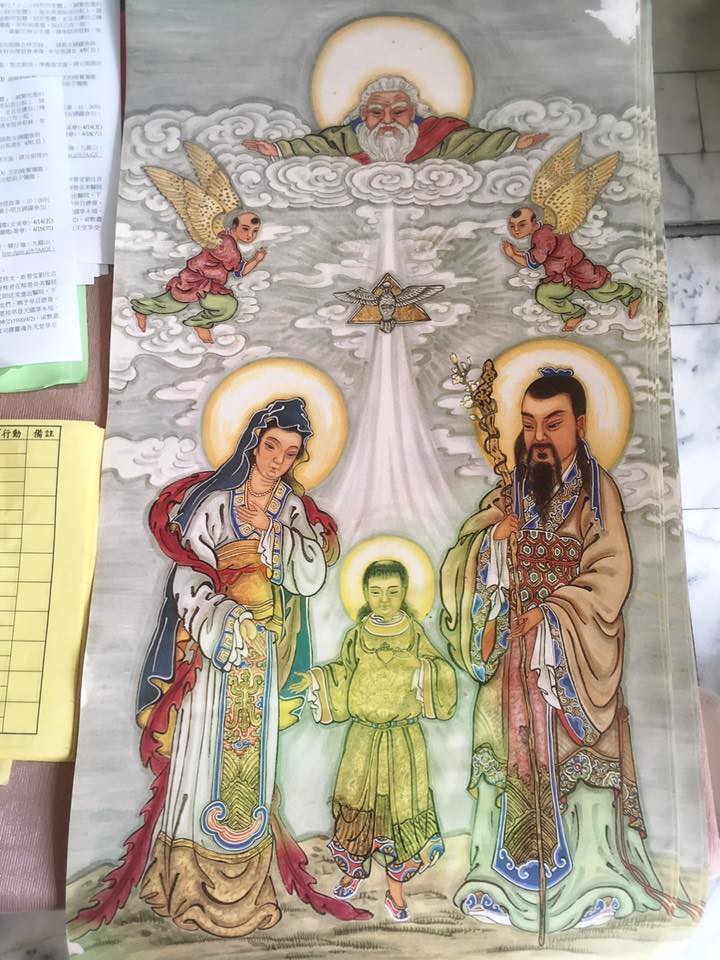

| A very "Chinese" Last Supper at the Catholic church in Yanshui, Tainan |

Something that's been kind of in the back of my head for awhile, brought to the fore by my friend Donovan's interview with a missionary, and then the editorial some guy wrote about it. Now I'm writing about the editorial. Perhaps someone will write a piece about my blog post, and someone will tweet about that, and someone will write an editorial about that incendiary tweet, and then someone will Snapchat it or Tinder it or Grindr it or Blendr it or whatever the kids are doing these days, right up until Donovan covers the whole thing on ICRT again. The circle of life.

Anyway, friends and regular readers will know that I don't care for missionary work. I understand that many missionaries do other good things for communities, but I can't condone the 'I claim to respect your culture but I actually think this part of my culture is better and you should trash what you did before' attitude, or the idea that one does good works toward the ultimate goal of converting people. I say this even as I acknowledge that I can like and even respect individual people of good character who are missionaries.

In any case, what struck me about Mr. Angrypants here wasn't his views on missionary work which I largely agree with, but this:

Academic institutions must focus on the enhancement of logical, critical and independent thinking. Unfortunately, core values of the local culture here are not amenable, often even inimical to such essential educational goals.

The prevailing culture here is authoritarian and honors blind obedience, its education awards rote learning without understanding, it discourages young people from thinking for themselves and it punishes inquisitive minds.

The disingenuous educational paradigms are implemented in so many classrooms here on a daily basis. Therefore, there is no need in Taiwan of an additional input of uncritical thinking by religious groups that aim to hijack the minds of young people through the indoctrination of dubious contents.

I don't entirely disagree with this, though I don't necessarily think my education was that much better. But, it can't be denied that this is a large component of the educational system in Taiwan. Every time I start thinking "oh it's not that bad", I recall a story an adult student (and legit genius and overall cool person) once told me. As a student, he'd had to write three essays, each on one of Sun Yat-sen's Three

I don't even blame Taiwan for it too much: it's a holdover from authoritarian rule (dictators want populations that can read, write and do math, but not think too much) that sticks because it claims on the surface to have cultural legitimacy (I'll come back to this). Changing it would take a complex organized effort that considered parents, professional curriculum development, exams, administration and long-term teacher development. I understand why it's so slow to happen.

In short, he's got his tenses wrong. The prevailing culture in Taiwan was authoritarian, but is now democratic with a strong penchant for social movements and activism. The education system just hasn't gotten with the program.

I also suspect quite a few Westerners fundamentally misunderstand the historic role of education in many Asian cultures. Yes, it involves a great deal of memorization, especially of the "classics" (or math equations, or grammar patterns, or whatever). If you do this, you will pass. But historically there has also been a belief that to be truly 'educated' - to be a scholar - it's not enough to simply memorize. You have to take what you've learned and glean insights from it that you can apply to real-world situations. You have to be able to use it, extrapolate on it, consider it, do something with it. Otherwise, you might pass, but you're not a scholar.

Or as we call it in the West, critical thinking.

I'm not an advocate of this particular method of leading learners to criticality and inquisitiveness - it's outdated and just doesn't seem to work that well - but it's simply not true to say that educational traditions in Asia sought to suppress such traits.

But that's not where the real problem lies. This is:

There is another reason for concern. It is obvious that so many young people in Taiwan are literally clueless about major issues that move the world. Their life experience is minimal, their minds are soft and malleable, underdeveloped, easy to bend....

Often, young people are emotionally and intellectually insecure; they have never developed their own ideas about topics of general concern. They are lost when having to move within competitive networks of opinions, assertions and claims — the stuff the modern world is made of.

Therefore, they can be easily manipulated and “guided” by those who do have opinions, no matter whether they are good or bad.

|

| Asian Mary, Jesus and Joseph (Frankly I'll take this over |

I'm guessing he doesn't spend a lot of time around Taiwanese student activists. If you think they are easily manipulated or their opinions can be changed or bent, just ask Ma Ying-jiu how that worked out for him.

Seriously, this is one of the most offensive things I've ever read about Taiwan.

Mr. Dude turns a somewhat-valid criticism of the educational system in Taiwan into a narrative of ‘these poor dumb mindless Taiwanese are at the mercy of these missionaries’ as though they are hapless victims too stupid and thoughtless to run their own society.

You know, that society that I just noted above has a strong tradition of activism (nevermind that it used to be called 'rebellion')? The one with arguably the most successful democracy in Asia, some of the freest press in Asia if not the world, with a developed economy that they (not the dictatorship) built?

That society, apparently. According to him, it's full of morons who don't even know how to have opinions.

This literally makes me want to spit. While I don't pretend Taiwan is perfect - there are many issues here that deserve strong, if not vicious, criticism - in this particular way, I have to wonder if we're living in the same country. I mean, sure, I meet idiots here. Every country in the world has its thinkers, its average people and its, um, dimmer bulbs. Every country has its leaders, its normal people and its blind followers. But to just not see all the creativity and insight around him? What's up with that?

For every thicker-skulled person I meet, I also meet people like my student above, who risked a failing grade just to write what he really thought. I see students occupying...all sorts of things, or trying to. I see the student I had who envisioned his presentation as a series of interconnected three-dimensional cubes, in a really insightful way that I hadn't even considered as a potential mind map. I see all the great Taiwanese fiction I've read recently, the beautiful films, the students I tutored who came up with a way to safely and more easily carry water over long distances while using the movement of that water to charge a battery that could be used for electricity, the creatively-decorated cafes, the young people with ideas that they'll launch once they get the money.

I see that while the authoritarian-holdover educational system in Taiwan is accepted, it is not particularly well-liked. Most Taiwanese are well aware of the flaws, and it's entirely understandable that fixing them seems like an impossible effort (if you want to criticize this, fine, but go look at American public schools in underprivileged areas and come back and tell me you still think Western countries are 'better').

I see a country where the education system doesn't teach critical thinking, but plenty of people learned to think critically anyway.

So this guy thinks he has all the answers for how to make Taiwan better and if we’d just do what he says those poor, poor, POOR widdle Taiwanese wouldn’t be taken in by those evil big bad missionaries. Just listen to him, he’ll fix what’s wrong with Taiwan.

He knows how to make this foreign culture better, more thoughtful in ways he can relate to, more like his vision of what it should be like. Of course, without his brilliant insight Taiwan will be lost. Barbaric. Stuck in the past. Or something.

In other words, he's just another kind of missionary.