I was delighted to get my hands on this short and snappy Taiwanese novel from the 80s. Both the writer and the novel itself are well-known, and in the latter case perhaps infamous, here. Yet, among my foreign friends, I can't name another person I know of who's read it.

If you don't think about it too much, this 180-page story might come across as a vehicle for every vice and bodily function, a thin plot providing the backdrop to fart-and-armpit porn, with prostitutes who never actually have sex, at least not in the events set out in the novel. It may seem fatuous if not self-indulgent, as if Wang Chen-ho's idea of being daring in 1981 was to include as much reference to body parts and bodily functions as possible and leave it at that.

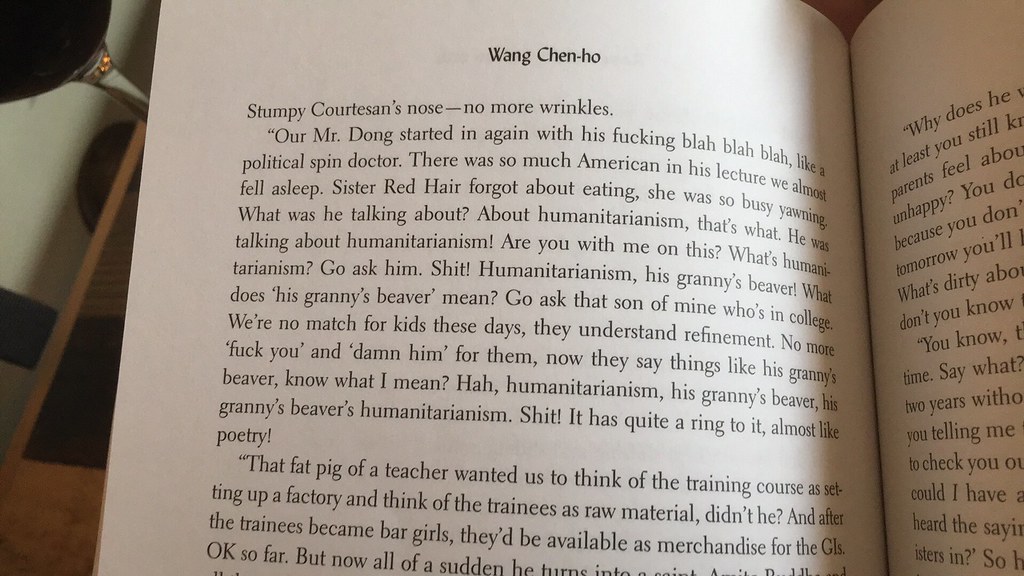

You'd be wrong, though. Now, I love a good fart joke and would describe my sense of humor as bent and filthy - I was born, not raised, this way - which those closest to me know and love, or at least tolerate, about me. My dirty mind and Rose Rose I Love You felt like a match preordained, a matter of fate, not luck. In fact, please enjoy an excerpt from this classic novel:

One of my first impressions was this: if you were in any way inclined to think that Taiwanese culture is 'conservative' or 'traditional' in a Western sense, you will be promptly disabused of that notion just a few pages into Rose Rose I Love You. It details a society that is interesting in how not conservative it is. I've written about this before, and it's worth going to have a read. Even Taiwan's tendency to be more friendly to Western ideas and cultural exchange is explored, to some extent, beyond all the prostitution, bawdy jokes and straight-up farting.

My second impression: there is a lovely phrase in Chinese that is, plainly, ~就是一個屁: it translates to "it's just bullshit/it's nonsense" but literally means "it's just a fart". I am, then, not so sure that the farting is in there for comic effect alone. Wang seems to be reaching fragrantly through the pages to impart to us the main point of his book, the universe, and everything: it's all farts. All of it.

After checking out the 2014 Taipei Times review of the same book (and learning a new phrase - 肥唧唧), my takeaways are a bit different. Perhaps because I have never read the original, so my knowledge of what the original language was and what it signified in a deeper sense is therefore limited to what the (excellent) translation provides as well as my Taiwan schemata, I missed certain aspects of this somewhat opaque story about a fat, clownish, provincial English teacher going to great lengths to plan a training course to turn common Hualien prostitutes into high-class bar girls for some visiting American GIs (whom we never meet - the novel ends as the training begins). I had to form a lot of my own impressions in something of a vacuum in that way.

Yet, throughout the novel, one cliched idiom kept popping into my head: "trying to make a silk purse out of a sow's ear". This saying has similar connotations to a Chinese idiom about an average woman - Dongshi - trying to look beautiful as a classic Chinese beauty - Xishi - but ultimately failing (東施效顰).

Teacher Dong (董斯文, though this is not stated in the English version and I spent much of the book thinking his name was 東斯文, or Eastern Refinement), thinking himself a dignified, educated and worldly gentleman, peppers his speech with English words and phrases - which the other characters repeatedly mishear or make fun of in bawdy Taiwanese or Mandarin puns - for example, turning position, as in a sexual position, into 破理想 or destruction of morals. He constantly reaches for an appearance of worldly refinement only to suffer from chronic flatulence, have his language misheard or derided by others and be repeatedly mistaken for a famous fat clown.

The prostitutes he is trying to turn into high-class bar girls - whom he envisions wearing gorgeous traditional dress - both Chinese and aboriginal - are, to be frank, rather common whores, and act the part as they are pressed into joining his training course. A few weeks of talks on hygiene, Christian prayers, "thirty English sentences", "global etiquette" and more are meant to turn these women into something they simply are not, in order to impress - and make money from - visiting American GIs. They are chosen based on the size of their breasts (like pomelos, not small oranges), age, looks, health and lack of menstruation. Councilman Qian, who makes several appearances, is supposed to be a brave and selfless servant of the people, having been elected in what would have been one of Taiwan's first local-level elections (full democracy didn't happen until 1996, but local by-elections were taking place as early as 1968, when the book takes place), mostly got elected for stripping on stage and showing everyone his rather large set of equipment. The bar the girls will work in is being built, and is described as being modern and inviting, yet towards the end it's noted in a parenthetical aside that there are no bathrooms and the only nearby ones are maggot-infested squat toilets. Even the song the girls are to sing as the American GIs arrive - Rose Rose I Love You - is given a double meaning, as a virulent strain of gonorrhea called "Saigon Rose" is quickly gaining notoriety among the denizens of Asia's whorehouses. The rich and popular town doctor sexually harasses, and quite probably beds, several of his male patients. It is implied that he has an armpit fetish. Teacher Dong himself, towards the end, basically spouts a repackaging of Audiolingualism as his own language-teaching invention that nobody else had taken notice of yet.

Nothing is too gross, or too low-class, for Wang to include to describe the seamy underbellies of every character parading around, acting as though they are better than they are.

It's hard not to read a complete takedown of urbane worldliness, beautiful women, educated teachers and even democratic elections in this. Everything in the novel is a sow's ear. Every woman is Dongshi, not Xishi. The teacher is a fat clown, not Confucius. The American GIs that everyone prepares for excitedly are probably swarming with venereal disease. And yet they are all pretending to be more than that - or at least Teacher Dong and Councilman Qian are, and everyone else is along for the ride.

I too read it as a satirical stab at Wang's memories of 1960s Taiwan - the prosperity and refinement of the Japanese colonial era fading (yes, I know, colonialism sucks, but the Japanese do have a very refined asthetic), modernization not yet begun, with Taiwan, its clothing patched and identity in shambles, trying desperately to impress a bunch of foreigners. It's hard not to read into it a full-on prison shanking of 1968 Taiwan, a sow's ear perhaps in Wang's estimation that is trying to be a silk purse on display for the Americans, that doesn't even know it's not. Not even one character makes it to the level of a joke - at best they are all punchlines.

This may sound bleak, but Wang also imbues these sow's ears with potential. Teacher Dong might well speak very good English, and what is essentially repurposed Berlitz is still better than whatever passed for typical English teaching at the time. Several of the bar girls are described as being quite beautiful, one is referred to as a "modern-day Lin Daiyu", almost as a Homeric epithet. The food that Big-Nose Lion and his aging prostitute girlfriend A-hen eat sounds delicious. Councilman Qian (I don't know which character it is, but it is a homophone with 錢, or "money", and I doubt that's an accident) seems to have a genuinely impressive member. These tiny droplets of hope glint across the narrative as though Wang is saying, in effect, "yeah, I know it looks bad now and these guys are a bunch of fools who think themselves kings, but don't give up on Taiwan. We really do have potential!"

Or, perhaps, he was saying "Stop trying to show off for the West, figure out who you are and celebrate it!"

And, of course, from the perspective of 2017, I can see that he was right.

I would love to comment more on the identity questions that were likely laid bare by the original text, but not having read the original, I'll let the Taipei Times review have the last word:

It could also be a searching look at a protracted moment in Taiwan’s history — one extending to this day — of testing out many trappings of identity, often for the purpose of outside consumption. But the novel is open-ended, offering no glimpses of its true self: In the final scene, the prostitutes intone the Lord’s Prayer and Teacher Dong launches into a reverie: The Americans are coming, greeted by 50 world-class bar girls wearing cheongsams or eye-catching Aboriginal dress. The ladies sing the titular song, Rose, Rose, I Love You, first in Chinese and next in English. Each is a shimmering ambassador of an ethnic identity none wholly inhabits, and no one is so sure of who she is.

No comments:

Post a Comment