While people who care about Taiwan's history and future certainly know who he was, it would be difficult for any sort of curious Taiwan neophyte to learn more than the basic outline of his story if they were not proficient in Mandarin.

What is written is often written by those in-the-know for others in-the-know, containing brief summaries of what we assume everybody knows. But they don't, always.

This is a shame. I would go so far as to say that understanding the spirit of Nylon Deng is key to understanding the spirit of Taiwan. Among foreign residents I know, there seems to be a dividing line between those who've never heard of him and those who admire him as strongly as any locals. Among local acquaintances, again, I have politically-oriented people in my circles who view him as an icon of the struggle for Taiwan's freedom and independence, and others who have to pause at the name to recall who he is.

I've never met someone who has learned his story and come away unmoved or unchanged by the experience, and so on Freedom of Speech Day, I feel compelled to provide a version of his story that fills in the gaps and perhaps helps to clarify why he is a hero to some, but forgotten by many.

The Freedom Era office where Deng self-immolated has been turned into a small museum, with the area where he died left untouched. His remains have of course been removed, but the burnt walls, floor and furniture have all been left in situ, behind glass panels.

I urge everyone to visit: the address is #11 3rd Floor , Alley 3 Lane 106, Minquan E. Road Section 3, Songshan District (台北市松山區民權東路三段106巷3弄11號3樓). It's open during business hours and you can ring the bell to be let in.

However, rather like most online resources, the museum is also entirely in Mandarin. With advance notice, an English-speaking guide can be arranged, and Freedom Era, the 1990s film about Nylon, does have the option of English subtitles. We were able to view it at the museum and at one of my visits, DVDs could be purchased. But that's about it. Otherwise, if you want to learn more, you're on your own.

Deng was born in Taipei in late 1947, about six months after 228. This may be one of the reasons why he became an active figure in the movement to push for wider recognition of that massacre. His father was Chinese, from Fuzhou, and his mother Taiwanese, from Keelung, and he himself noted both the significance of having one "Mainlander" and one Taiwanese parent, as well as the tragedy of his birth year. He spoke out both of his family being targeted for their background, but also of being protected by neighbors.

He would say of his background that although he had Chinese ancestry, he supported Taiwanese independence, a message that might resonate with many today. No small percentage of my friend circle, for example, have grandparents who came to Taiwan in the 1940s, and yet all of them think of themselves as Taiwanese. Even the ones who aren't particularly 'green' or 'blue' support independence; I don't know many people under age 40 who don't, and data suggest that very few identify as 'Chinese'.

Deng studied engineering at National Cheng-kung University, but found he was more interested in philosophy, at a time when students were still bombarded with KMT propaganda as part of their education. Famously, he transferred from Fu Jen Catholic University to National Taiwan University, but then walked out for refusing to take the then-required class in Sun Yat-sen Thought. This is also around the time he met his wife, Yeh Chu-lan, who became a political figure in her own right after Deng's death. I've heard stories about their relationship, which I staunchly view as none of my damn business.

After finishing school, Deng wrote for several magazines, including Deep Cultivation and Politician, and would spend hours at the Legislative Yuan listening to proceedings (which is not something I had thought one could do at that time!)

In the early 1980s he started Freedom Era, a magazine aimed at fighting for "100% freedom of speech". If you've ever seen the graphic of an open mouth in a prison cell, with one bar bent, this is where it comes from. If you have any familiarity with "political magazines" from earlier eras in Taiwanese history -- most notably the Japanese era when publications such as Taiwan Youth and Taiwan People's News were founded -- you'll know that Freedom Era was a continuation of the tradition of activist publications in Taiwan.

The KMT government banned the magazine several times, and it was re-opened under a new name each time. It was said that readers always knew where to find it regardless of the name, and in any case, all of the names were similar. Freedom Era racked up 22 publication licenses this way; you can see the stamps for them in the museum.

Freedom Era included contributions by many leading activists and writers of the day, including the usual Tangwai pro-independence set but also some we might find surprising today, such as Li Ao, a writer from China known now for having been anti-KMT, but also pro-unification. A volunteer at the Nylon Deng Memorial Museum noted wryly that such collaboration did not last. Wan-yao Chou points out in A New Illustrated History of Taiwan that had the democratization movement gone differently, perhaps pro-democracy 'blues' and 'greens' could have worked together more. Instead, they seemed to split among independence/unification lines.

Deng was always clear, however, that he advocated for independence; Taiwan's democratization should not be in hopes of unification, but sovereignty as Taiwan. One of the most famous snippets from his speeches is simply "I am Deng Nan-jung, and I support Taiwanese independence" -- nothing flashy or unique, but not something most people would have dared to say in 1987.

According to the preface of Taiwan's 400-Year History, Deng helped smuggle copies of the book to Taiwan. The book itself is is Su Beng's seminal (and highly editorial) history of Taiwan the first of its kind to give Taiwanese readers the chance to frame their own history as something separate and unique, not a part of any concept of "China" or "Japan".

Many of Deng's remarks became famous both in their time and after. These include"if I could only live in one place, it would be Taiwan. If I had to choose one place where I would die; that place would be Taiwan." And, in a sense of dreadful premonition, "the KMT will never take me, they will only take my dead body" and "I'm not afraid of being arrested or killed, I'll fight them to the end."

Back to the story. This cat-and-mouse game continued with the KMT, and one can only imagine the extent to which Deng himself was aware of how it might end.

In the mid-1980s, Deng served a few months in prison for violating censorship laws. In 1987, helped organize 519 Green Action -- a protest on May 19th at Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall demanding an end to Martial Law, which was lifted in July of that year. It's hard to say who attended the protest as so many turned their backs to cameras, but one might guess that many were ordinary citizens.

Shortly after Martial Law was lifted, Deng initiated a campaign to push the government to designate 228 as a national holiday. To this day, Deng's brother, co-activists and the Nylon Deng Liberty Foundation and others collaborate on efforts to boost the remembrance of 228, most notably a march through the area where the incident occurred. The march typically covers the site of the Tianma teahouse where Lin-Chiang Mai was beaten for selling cigarettes illegally, the Executive Yuan and the radio station in what is now 228 Peace Park where protesters took over the broadcast and asked all of Taiwan to rise up against the KMT.

By 1989, the year of his death, Martial Law was well over, Chiang Ching-kuo was dead, and Lee Teng-hui had succeeded him. Lee does not deserve direct blame for Deng's death, certainly the sorts of reforms he pushed through against the protests of a reticent KMT took time (did you know that some Taiwanese political prisoners remained behind bars until the early 1990s? Here's just one example). However, I think it's important to remember that when Deng died, the Chiangs were gone and the man credited with a critical role in democratization was at the helm. The world isn't simple; things don't always make narrative sense.

In 1989, the KMT moved to arrest Deng for "insurrection", as he had published a proposal for a revised constitution. It is unclear when Deng had begun collecting cannisters of gasoline, but he stayed in his office for about 70 days as friends brought him food and water. Remember, he'd also said the KMT would never take him, only his dead body (國民黨抓不到我的人,只能抓到我的屍體). Anyone with forethought would have understood what he was planning.

Then, a police charge led by Hou You-yi -- now the popular mayor of New Taipei and possible 2024 KMT presidential candidate -- attempted to charge his office. Rather than be taken, Deng poured the gasoline he had collected around his office and set himself on fire. He died in the blaze, which was covered by Formosa TV.

Here is something else you should know: that footage can be seen in the film Freedom Era. It's extremely difficult to watch. I shut my eyes for much of that part; I just couldn't. Even so, I could hear Yeh Chu-lan screaming on the tape. As much as I might like to, I will never forget that sound.

A few years ago, Hou came under fire for some stunningly insensitive remarks about the Nylon Deng tragedy: that they weren't just trying to arrest a man, but also "save a life".

There are no words for this. Even if Hou was unaware that Deng had been collecting gasoline cannisters -- and perhaps he was -- he would likely have known that Deng had said the KMT would take nothing but his dead body. Maybe he thought it was a bluff. Perhaps he truly believed no lives would be lost that day. Somehow, however, I believe he was aware that a person with a spirit like Nylon Deng was never going to come quietly. I believe he knew that Deng's words were sincere, and went in anyway.

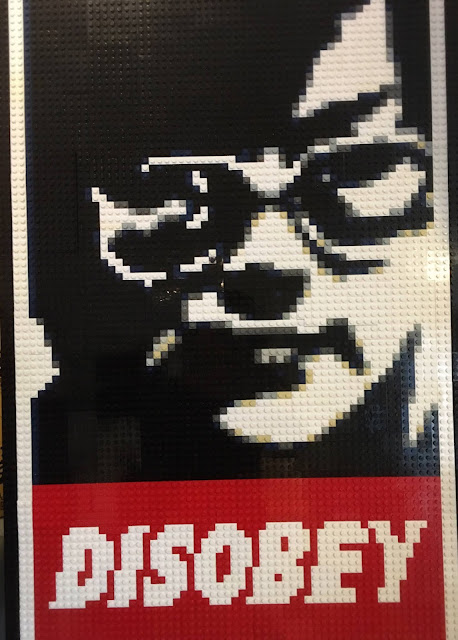

This is the man who might run for president in a few short years. As long as I've lived here, I don't think as a foreigner if it's my place to show up alone at a Hou 2024 rally carrying a massive sign which is simply a picture of Nylon Deng, holding it silently in the air. But if he does run, and any of my Taiwanese friends want to do it, I'd be happy to help both make and hold the picture.

Deng's funeral procession was massive: there's a film about this too. Thousands of people turned out despite threats of violence, and if I remember correctly, much of the organization was handled by the Presbyterian church in Taiwan. I don't recall if Deng himself was Christian, but he'd worked with the Presbyterians before, and a pastor had met with him shortly before his death (link in Mandarin). Apparently, at that time, he pointed at a cannister of gasoline under his desk, announcing his intent to self-immolate if the police attempted to arrest him.

As the funeral procession got underway, not only was Deng's daughter, Deng Chu-mei, attacked with acid (she was unharmed), but Chan I-hua 詹益樺, a fellow activist, also self-immolated on what is now Ketagalan Boulevard, in front of the Presidential Office, when the police would not let him pass.

Although I can't remember the source, I have a memory of photos of Yeh Chu-lan and Deng Chu-mei soon after Nylon's death, as Yeh stepped into politics. It's heartbreaking. Deng, in elementary school when her father died, also drew a picture of him in Heaven, asking him not to smoke or eat too many sweets, along with a poem: "My father is like the sun; if the sun is gone, I will cry and cry, but still I cannot call it back."

A friend of mine once told me that Nylon Deng knew that his self-immolation could be the spark that would ignite pro-democracy and pro-independence activists and get done what needed to happen for Taiwan. I don't know if that's true, but I do know that despite admonishments that Deng is being forgotten, not everyone has let his memory slip away.

His death has inspired the spirit of independence activists who came after him, many of whom visit the museum annually. I wouldn't be surprised if some were to go there today.

Taiwan in 2021 sits at the crossroads of what seems like an impossible situation: China refuses to renounce the use of force to annex the country, but the consensus of the 24 million people who live here is that this can never be allowed to happen. It is unclear to what extent the world would step in if China were to invade, and I think it's likely they are intending to try eventually (although it's difficult to say when).

What resolve can one muster in the face of this, if not indomitable spirit to keep fighting and refuse to let the CCP have this country? Whether you think self-immolation was the right choice or not, Nylon's will to not give in is what has continued to inspire admirers from his death until today.

In the 1990s, the Freedom Era office where Deng died was opened as a museum, as mentioned above. It's free to visit, but only open for limited hours as the staff are volunteers.

In 2014, not long before the Sunflower Movement, students at Cheng-kung University in Tainan fought with the administration over naming a public square after Nylon Deng. The administration rejected the students' vote, and one professor even likened him to an "Islamist terrorist". Yeh Chu-lan and Deng Chu-mei invited the NCKU president to the Nylon Deng Memorial Museum, though I doubt he went.

In 2016, the Executive Yuan named his death Freedom of Speech Day, although there's no accompanying day off as with other national holidays.

Over the years, Deng's words continue to be enshrined in Taiwanese music. "If I could only live in one place, it would be Taiwan, if I had to choose one place where I would die; that place would be Taiwan" can be heard at the very end of Dwagie's Sunflower, and "Nylon", his song focused on Deng -- which takes on the rhythm of a Buddhist sutra more than a rap -- uses many of Deng's own words, including the darkly prophetic quote about his self-immolation, and features vocals by his widow, Yeh Chu-lan. Chthonic also has a track (Resurrection Pyre) honoring Deng, with what I believe is a fan-made video. Indie rapper Chang Jui-chuan included him in "Hey Kid", a song about those who fought for freedom in Taiwan and the lessons a father hopes to pass on to his children about their struggle.

In addition to the tributes by some of Taiwan's most well-known musicians linked above, Deng has also been memorialized in visual art. Most recently, a now-closed exhibit at the Tainan Fine Art Museum -- Paying Tribute to the Gods: The Art of Folk Belief -- imagined Deng and Chan as guardian gods. Their neon likenesses reminded one of Matsu's Thousand-Mile Eyes 千里眼 and Ears on the Wind 順風耳 as they stood guard over a ceremonial palanquin at the center of the final exhibition room. Around the palanquin, one could read paper-based ephemera from their lives, as films played on screens at the back. One of the films, of course, was Freedom Era.

I'm not sure exactly why I'm telling you all this. I'm not from Taiwan. I suppose I have no cultural or ancestral right to consider Nylon Deng a hero, but I do. I can see why new generations of politically-minded Taiwanese do, too.

So rather than complain that not enough people are aware of Deng's legacy, or that his spirit is not being suitably honored, I figured that the best I could do was to recount the story on Freedom of Speech Day 2021, in English, in as complete a form as I am capable of, so that more people might know.

Try to remember in 2024, when it will really matter.