|

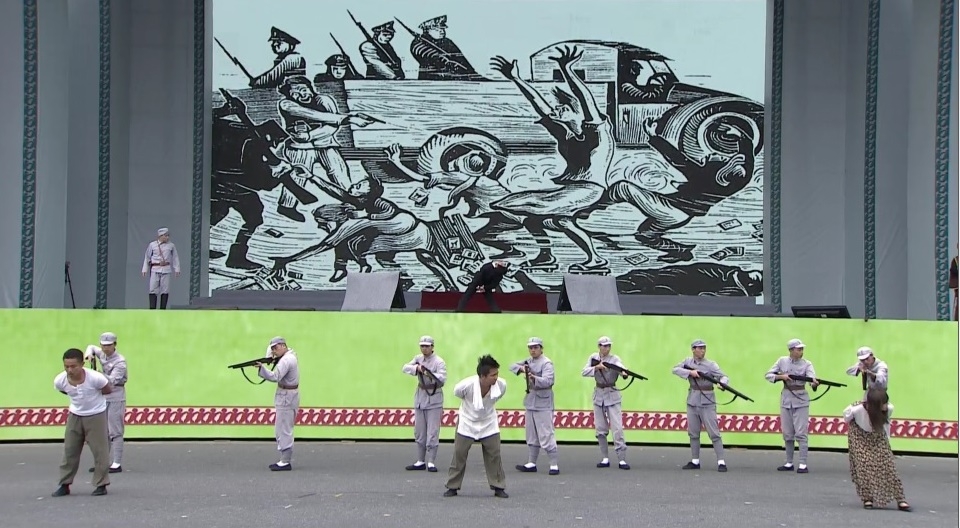

| I don't have a good cover photo so just pretend this is metaphorical or something. |

I've been meaning to write this for awhile but current events have been pushing it to the bottom of the queue. Feeling depressed and anxious about the state of affairs in Hong Kong and the rise of Big Uncle Dirk in Taiwan, however, I think it's time for a more uplifting topic.

Teacher training has been my main source of income for about a year now; my trainees are mostly (though not entirely) locals whose first language(s) are not English, but are highly proficient English users. There's a mix of experience levels, though most have had no previous training.

In the real world, where this is what I'm 'known' for as much as talking smack about Taiwanese politics, I get asked all the time what it's like, how I feel about it, what my impressions are. So I thought I'd share something about that here, as I so rarely write about my actual profession.

Having no particular order in mind for this, I'll just start with what I think is the most interesting part, focusing mostly on the cram school system.

Native speakerism has been, quite honestly, a cancer in English language education in Taiwan.

I appreciate and value that the work I do is one tiny cog in the fight to end that. Training local teachers who already have the language proficiency but need the classroom know-how to plan and execute a lesson, ascertain and meet learner needs, manage a class room and understand key theoretical basics gives them a leg up: a piece of paper, yes, but also actual knowledge and skills that will make them more effective in the classroom and therefore more likely to succeed in a market that is biased against them.

Not that the word 'native speaker' means anything. I have a former student whom you would not be able to guess, even by accent, was a 'non-native' speaker unless you combed carefully through her writing. I've also met 'native speakers' who were not particularly proficient language users (yes, that's a thing, and the major English proficiency tests generally acknowledge this) and people who have used English since early childhood from countries like India, Singapore and the Philippines but are considered 'non-native'.

Because, of course, when people say "native speaker", what they really mean is "white". They'll deny that of course - I'm sure I'll get some angry comments - but you it's true. You know it's harder for non-white English teachers, whether they're what might be considered a 'native speaker' or not, to find jobs and command similar pay to white teachers. This was also the attitude on display when everyone's favorite Uncle Dirk dismissed the idea of English teachers from the Philippines (who generally can be considered what most people would call a 'native speaker'), saying "how can a Maria be our teacher?"

Although I don't think that there is a big difference in the classroom between an untrained foreigner and an untrained local with strong English language proficiency, it's hard to argue this to your average person. Training up locals on what I think is a quality course helps make the argument that a "non-native" teacher is no less capable just a little more persuasive.

To be frank, it also feels good to have mostly relinquished my former place in what I see as a racist system. I don't particularly like being a white lady taking up a teaching job that an experienced and trained local could do, and being paid more to do it. It's not that I want to stop all future foreign English teachers from coming here because all the jobs have been taken by locals - I just want the bar to be higher, and the best way to raise the bar is to have better-trained local talent as competition. Bringing in trained and experienced talent from the Philippines and other countries is a great idea as well, and that will be easier if more parents and students (including adult learners) get used to a non-white face leading the class.

This is related to another aspect of teacher training that I find deeply rewarding: the creation of future role models. My trainees, when they become teachers, can be role models to local learners in a way that I could never be as a "native speaker" from an Inner Circle culture (look it up). Someone learning English as a foreign language in Taiwan is going to have a different experience, context and set of reference points and will benefit from having someone with a similar background and experience to look up to and think, "if she can do it, I can too". That's not only more achievable than trying to be 'more like' someone like me, which sets up the impossible standard of learning English as a second language in an attempt to imitate people for whom it's a first language, but I'd argue it's less problematic as well. If the notion of encouraging Taiwanese to imitate Westerners - especially white Westerners - as though we are some sort of ideal - doesn't squick you out...it should.

Here's where I admit that I lied above: I don't think that's the most interesting issue concerning my job. But I needed to say it to set up my next point. The cultural/identity aspects of Taiwan's education are often thought of as being in flux, depending on who's in power, between "Taiwanization" and "Sinicization". I'd argue, however, that since the debate about identity formation through education has existed in Taiwan - that is, ever since the Taiwanese electorate had a say in the matter - that it's actually been a three-way pull between Taiwanization, Sinicization and internationalization. It's a bit more complicated than that, with both sides trying to claim 'internationalization' alongside their preferred foundation of 'Taiwanization' or 'Sinicization' and both sides being somewhat insincere in the implementation process (though I'd argue the 'Sinicization' side, which I'm sure you've guessed is spearheaded by the KMT, is somewhat more insincere).

I also happen to believe that 'Taiwanization' is more compatible with internationalization than 'Sinicization' is, despite being dismissed by critics as a form of ethnic nationalism (which it no longer is - if anything that attitude is more evident on the pan-blue, pro-China side). Taiwanization doesn't only seek to promote the notion of a distinct Taiwanese identity, which is a civic identity as much as an ethnic one, and a nation founded on that principle. It also seeks to situate that identity, and Taiwan as a nation, in a regional and global context. Sinicization doesn't go far beyond "we are all Chinese and you just have to accept this identity we've assigned to you". Although this wasn't always the case, it's currently more of an inward-looking movement.

What does all that have to do with teacher training? Well, a lot of people misconstrue 'internationalization' as going no further than a concept of English teaching as something done by foreigners, to Taiwanese students - and bringing in more foreigners to do this. The smiling white person at the front of the classroom telling Taiwanese how to be better "global citizens" through improved English, with "global citizens" of course meaning "people who act in ways that make Westerners feel comfortable".

In a word, barf.

I see internationalization as improving the state of foreign language education without overly focusing on Western countries (which isn't to say that language can be divorced from culture - the general consensus in the field is that it cannot). It's understanding not just the cultural, international and socieconomic context of English learning, but English learning as appropriation - learning it for one's own purposes, to communicate with the outside world as a lingua franca - rather than subjugation to a foreign ideal. And you don't accomplish that with idealized Westerners at the front of every class. You do it with locals up there, or teachers from a range of international backgrounds beyond "Bill is from Canada, and Janice is from the UK!" It helps society get used to the notion that English doesn't have to be a "thing we learn from and about white people", but something additive rather than subtractive, taught for themselves and (mostly) by others who may be like them. And you accomplish that by training up mostly local teachers.

Finally, I simply appreciate a chance to offer the fundamentals of good teaching practice to teachers who will go out and not only use them, but build on them. It's been argued that the sort of approaches I champion are themselves ultimately derived from teaching practices that suit Western cultures better, but I'd dispute that. First, we do talk about methodologies that are currently out-of-fashion, though I don't encourage them. Besides, such methods weren't common in Western countries either until the late 20th century: before that, the way language was taught wasn't that different from how it's taught in much of Asia now. The difference is one of time and institutional constraint, not one of culture.

More importantly, those 'traditional' methods are research-proven to be less effective, depending on what your goal is. If that goal is to communicate, do you think sitting in a 50-person class memorizing texts and repeating grammar points will be the most effective approach, regardless of culture? That English class in Taiwanese schools alone, without outside practice, does not lead to particularly stellar results, should be sufficient evidence that it will not.

But, most vitally, it's that local teachers and students have shown themselves to be open to other approaches. Despite unfounded stereotypes to the contrary, your average Taiwanese student does want their language classes to be more vibrant - fun, useful, communicative - than a traditional grammar-focused approach affords. Your average Taiwanese teacher wants to deliver that, as well, although institutional constraints (such as testing requirements) make it difficult. And as time passes, some of my best students will become head teachers or teacher trainers themselves, and will impart their own advice on what works and what doesn't, and "what works" will be forged of an entirely home-grown consensus. That can happen without me in the picture, but I feel grateful that I get to be a part of it.

That's just it - I'm not seeking to put people down (such as untrained foreign teachers who come and get jobs easily) or push my own ideas on others. I just want the state of English teaching in Taiwan to be better. My Big Bad - my Final Boss - is probably the national-level exam (and the over-testing that takes place leading up to it). Although there have been changes and improvements, it's not nearly where it needs to be in terms of creating positive washback on the classes learners take. There's not much I can do about that now, but if the overall state of language teaching is both more localized and simply better, it's a step in the right direction.