There was an interesting piece in Taiwan News recently about why marriage equality, not the labor movement, is attracting demonstrators and catching the public eye. I would especially like to learn more about traditionally Taiwanese representations of gayness as I know basically nothing about it.

I don't agree with every conclusion - in fact, although marriage equality impacts a small segment of the population, it affects that segment in a huge way, and is something of a social litmus test for the kind of country Taiwan wants to be.

I do not think allowing bigots to score a point by allowing civil partnerships is the answer: first, because I don't believe in giving in to bigots (could you imagine telling, say, African Americans to compromise with racists during the Civil Rights Movement and accept less than full equal rights? This suggestion doesn't feel different), especially when they are a small minority with outsize influence that it's time we cut down, and secondly because it's a straight-up human rights issue.

So, I cannot accept the conclusion that we need to let marriage equality go and focus on labor: in fact, I think we should ramp up marriage equality, get it passed quickly, and then focus on labor. I am not a fan at all of the argument that we should delay conferring full civil rights on a group because they happen to be a small group and because some bigots don't like it. I do not think a new law - rather than amending the civil code - will bring about the realization that marriage equality is okay, leading to later change in the code. It'll get stuck there. We'll try to push for the civil code to be changed, only to be told "but we HAVE marriage equality, can't you just accept that and move on?" The bigots will not stop being bigots, they'll bring out the same old fight. It'll be a bureaucratic nightmare, a postponement of the real battle. I'm not into that, sorry.

My views, however, mean little - I can't vote and I can't organize. It's what the Taiwanese are inspired by that counts. I have a few anecdotal thoughts for why labor is not attracting crowds but marriage equality is:

The marriage equality crowd is a young crowd, many of whom do not intend to accept jobs with poor working conditions when they graduate.

This is the generation that gets involved in public life, that goes abroad, that starts their own business, that goes freelance, that moves back to their hometown to open a cafe or run their family business. Some of them are surely on the naive side, thinking they have an escape route from the hell that is a typical job in Taiwan, and some will likely come to regret their idealistic assumptions. For many, however, that is a fuzzy eventuality, a gray cloud on the horizon. They have gay friends now, this means more to them.

Turton is right about one thing, though: marriage equality is cool and trendy and progressive, but labor movements often call to mind the sad reality that most of us eventually end up working for The Man. They're not young, hip or cool (and, as the article also got right, they don't tap into an identity one can display through consumption). When you either don't want to think about your eventual working life, or don't think it will happen to you because you'll never be stuck in some interminable cube monkey job, your heart is just not going to be in a labor protest.

I just don't happen to think all of that identity-broadcasting done by demonstrating for marriage equality is necessarily a bad thing. We all do things to display our identity. I do it, Turton does it, we all do it. For some, it really is a representation of who they are (if you're gayer than a Christmas tree and act like it, then is that not authentic rather than an identity you have chosen to display through consumption? If you really are someone whose fire gets lit by human rights causes, as I am, are you not being authentic in displaying that identity even if through consumerist means?

This is about more than just being fashionable, or a way to display an identity

A friend pointed this out, and I agree. Yes, there is consumption, identity display and some amount of being attached to a fashionable cause when it comes to marriage equality, but 250,000 people don't turn out on a Saturday for that reason alone. It is far more than the core LGBT+ fighting for equal rights and other activists passionate about the cause, and shows a deeper engagement than just being trendy or hip. You might get a few of those, but you don't get 250,000, especially when they were not brought out by tight, cohesive church networks the way the anti-equality folks were with their far smaller numbers, if it's just people showing off how cool and progressive they are. People do care, there is real support, and it does go deeper than strutting around in order to cement an identity for oneself.

Honestly, the labor movement doesn't get the word out effectively.

I don't know about you guys, but I always hear about marriage equality events well in advance, and can plan to attend them. Labor protests? I read about them the next day from Brian Hioe, or see them happening when I am already in my pajamas. I don't know until it's too late that I could have been there. I don't know how they hope to attract more people if people don't even know something is going on.

Marriage equality seems solvable, labor issues do not

I think a lot of activists know they have society and even much of the government on their side in the marriage equality debate. They know this is winnable. They know it's winnable soon - a big victory in a short time over an opponent that is outmatched. The fight against the Boss Class will be a long, grueling, interminable one with a huge amount of media, money, crony capitalists, corrupt politicians and straight-up asshats bearing down on them. It will be another Sunflower Movement, if we let it get that far (and I do think labor has the potential to be that, but few seem to agree) - an angry group of activists up against insane odds. Perhaps the nation is still a bit hungover from the last big movement, and wants a break, to achieve something that can actually be done.

Hell, the New Power Party has a pretty strong labor platform (though as always I do not agree with their past resistance to relaxing the laws governing foreign workers), and they can't seem to get anywhere. If they can't bring the crowds, or effectively stand up to the Boss Class, how can anyone?

Marriage equality, though? Dude, we can do that.

It's not really clear, due to deliberate muddling, what the labor movement really means or stands for

Which labor movement are we even talking about? The one opposed to pension reform? The tour guide protest? The fakey-fake "Sunflower imitation" protests the KMT organizes because it just does not get civil society at all? Or the real labor protests? It's easy to be confused. I often have to think hard about a demonstration - if I even know it's going to happen - to see if this is a group I actually agree with, or just more civil servants unhappy about pension reform when most workers in the private sector don't even have pensions, or only nominally do. The labor movement needs to clarify who they are, what they want and who they are not, or they're just not going to bring the crowds.

Workers themselves seem to vacillate between grumbling about the situation - and I agree that it is dire - and talking about how "this is just the way things are", not complaining, not talking to their bosses, not going to the company to air grievances. If workers won't even tell their bosses what they don't like, how can we expect them to get riled up enough to protest? And how can we expect others to come out on behalf of them when they won't stand up for themselves at work?

The fight for more vacation days was, to be honest, uninspiring

I'm sorry, I just can't work up a lot of screaming, placard-waving enthusiasm over keeping Chiang Kai Stupid Shek's Stupid Birthday. I know a vacation day is a vacation day and I shouldn't fret so much, but...I just can't get over that. I don't know about the rest of the Taiwanese public, but it's not a galvanizing message.

Add to that the fact that we've only had these extra seven days for one year: in the past ten years in Taiwan I never had those days off, and suddenly I do. It's very confusing, and I don't feel passionately about keeping them because they sort of randomly appeared this year rather than being something I'm used to that fits into the rhythm of the year.

So, it just doesn't seem like a smart route to go in terms of igniting a fire in people to come out and fight.

It is uninspiring to fight for better labor laws when the ones we have are not enforced.

A friend brought up this point (and the point above about workers who don't complain) and I agree enough to include it. Sure, we need better laws, but what good is it if the ones we already have are more or less never enforced? Who cares if a new law limits overtime if you can't get your boss to abide by the current laws regulating overtime? What are we fighting for, exactly?

That young marriage equality crowd has free time, workers just have stress

...and workers generally do not.

Those that do face family pressure - always a big deal here - to keep their shitty job and not rock the boat, or to 'take what you can get'. It's a society that is very accepting of market trends in terms of how workers are treated - in the US the left screams and howls, rightfully so, when capitalists say that a fair wage is the lowest wage someone is willing to work for, but Taiwan is far more accepting of this explanation. Something about that "this is the best we can do, this is the market, we have to accept it" attitude has to change.

Workers are also less idealistic. They've done jobs, they know how the world is and how most of us eventually get sucked in (for the record, I'm in my 30s and have still managed to not get sucked in, but I may well die old and poor). They are often focused on themselves and their families - by then, most have them - and improving their own lot rather than fighting for the betterment of all. This is another attitude we have to change.

In the meantime, though?

Honestly, you'll find me in the street, rainbow flag in hand.

Thursday, December 22, 2016

Wednesday, December 21, 2016

Fighting Native Speakerism in Taiwan

I don't blog much here about English teaching, because to be honest, it's my job. I happen to love it, and I happen to be a professional, and I want to talk about it, but...it's my job. I may start a specifically ELT-related blog someday, but otherwise I generally tend to keep my hobbies (like snarking on Taiwanese politics, activism - to the degree I am able - writing and travel/exploration) separate from my profession. It's funny, though, because I'm actually qualified to comment on ELT matters, whereas despite my related degree (International Affairs), I'm basically a hobbyist with a snarky streak when it comes to politics.

However, something about this really ought to be said. First, a primer in what 'native speakerism' is.

None of this is new - there is a whole organization dedicated to fighting native speakerism. But, to get into why it's difficult to fight in Taiwan, I feel the groundwork needs to be laid.

Native speakerism is a global issue - preconceived notions about what makes a 'teacher' due to a lack of general training in ELT issues (which is fair - not everyone is going to have a basic knowledge of education theory) causes learners to believe that native speaker teachers are superior and schools advertising the usually (but not always) white, Western faces of the teachers with correspondingly high tuition preys on notions of 'prestige' in teaching. Learners then request native speaker teachers, leading schools to then discriminate against non-native speaker teachers in hiring, and blame it on "the market" - a market which they helped create. It doesn't help that a horrifying lack of professional standards makes it possible to get a teaching job with no qualifications or experience to speak of other than being a native speaker, and that the owners of language schools are often local businesspeople, not educators, and do not know themselves what to look for in a quality teacher - they too boil it down to "native speaker, looks the part, cheaper than a trained teacher, you're hired."

One can add to that a big fat dollop of outdated assumptions of what it means to be a "non-native speaker". People who don't know better will insist that "non-native speakers can't possibly know all of the idiomatic language, rare collocations and modern usages of English, they'll teach a more textbook English", but that assumes quite a bit about a native speaker. An Egyptian woman who spent the first ten years of her life in Cairo, but then moved to England and had lived there ever since, for example, would speak at a level so close to native that you would not know she wasn't a native speaker, and would have more knowledge of British idiomatic language than I do. How is she less of a 'native speaker' than I am? A Taiwanese student who went through an entire school curriculum at TES or TAS, who might speak flawlessly - you might mistake her for an Asian woman from the West - is she a native speaker? My own grandfather grew up in Greece and moved to the US in elementary school. His native languages were Western Armenian - there are a genocide and two escapes in that story - and Greek. To hear him talk now you would never think of him as anything other than a native speaker of English. Is he? Why do you assume all native speakers speak an imperfect, textbook-y or even 'foreign accented' (again, whatever that means) English?

And that's not even getting into issues of cultural or linguistic imperialism and the notion that only "native speaker English" (whatever that means) is "good enough", or that there is something wrong with local varieties of English!

What really goes into teaching well is, of course, a high level or native-like level of English: something many non-native speakers attain, as well as sound training (whether it confers a credential or not - the piece of paper is not the point, though it's hard to gauge the quality of non-credentialed training) and increasing levels of responsibility through experience. Some level of basic talent or affinity for teaching helps. Research agrees: if the level of English is sufficient and the teaching is pedagogically sound, the first language of the teacher makes no difference.

I find this a very convincing set of arguments for doing away with discrimination based on first language in language teaching, and yet the problem persists in Taiwan. Why?

The law is outdated

There are conflicting accounts of what the laws actually say. Most non-native speaker teachers in Taiwan are Taiwanese themselves, students on a student visa that allows work, or other foreign residents married to locals. A few have Master's degrees and therefore can be hired for any job. It is unclear whether, legally, visas for non-native speaker teachers who come to Taiwan simply to teach can be procured by schools however. I have been told "no", I have been sent unclear links with confusing language, I have been told such visas have been successfully issued, although every example seems to be of a white European. I have been told English must be the 'official language' of the country of origin, but the US has no official language, and plenty of countries people don't think of as English-speaking, such as Nigeria and India, do have English as an 'official language'.

However, I have also heard firsthand accounts of non-native speaker, non-Taiwanese foreigners trying and failing to get a visa to teach English because they held the "wrong" passport (not from Canada, the US, Ireland, the UK, South Africa, Australia or New Zealand). So, let's just say that the law is unclear but if you are not a native speaker, and do not have another pathway to a job that doesn't require a school-sponsored visa, and lack a Master's degree, that it is likely to be difficult for you to procure a visa to work in Taiwan.

This is in direct contradiction to research on effective teaching, and yet it remains a problem. When it is difficult to get a school to even offer a job to someone they know they may not be able to get a visa for, it makes sense that schools would go for candidates for whom visas would be promptly issued.

So what can we do?

Honestly, I have no idea. You can lobby the government - good luck with that. You can write an editorial - nobody will read it. You can try to raise awareness among locals inclined to do something about it, but so few are even if they agree with you. If you ever do find yourself with the right kind of guanxi in the government, this would be a great place to use it to bend someone's ear. For now, however, I'm at a loss.

It's hard to know which schools would not discriminate, given the choice

It's very difficult to know what a school would do if it didn't have this potential legal hurdle to hiring non-native speakers and very difficult to fight, as it requires a change in the law.

My various employers, for example, are all good people. They're sensible and they have some foundational knowledge of the qualities needed in a good teacher. I do not want to think that, given the chance to hire a non-native speaker teacher who would need a visa, that they would discriminate. However, due to the confusion and difficulty inherent in the law, it is hard to be sure. How can I talk to my employer about a problem if I don't even know if it exists, or if it only exists hypothetically?

In my school I noticed an advertising sign-listicle sort of things ("10 reasons to study with us!" but at least it didn't have something like "#8 will shock you!") where one of the items was "Canadian, British and American teachers: the world of IELTS comes to you!" - what does that mean exactly? Is that pro-native-speakerism? Would they discriminate against a talented, native-like and qualified non-native speaker if given the chance to hire one? It's hard to say. It's just an item on a list tacked to the wall, and there's no way to test the sincerity of it. How does one even bring that up?

This makes it difficult to have these conversations with employers - note conversations, not confrontations or arguments - when you can't really know where they stand. When perhaps they themselves don't know where they stand. It's hard to push the issue further or raise awareness.

So what can we do?

One of the core messages of TEFL Equality Advocates is for native speaker teachers to use their privilege to help change the system: not applying to work at schools that discriminate, withdrawing one's application from a school that indicates that it discriminates later in the process, and writing to such schools to tell them why (in gentler words, of course).

It's difficult to do that when you can't know if a school would discriminate if they didn't have to by (very confusing) law. What you can do, though, is bring it up if the opportunity arises and try to gauge your school's attitude towards native speakerism, and take it from there.

The 'native speaker' model is still seen as the best, or only, choice

This is a massive problem in a world where ELF (English as a Lingua Franca) is the English that most English speakers - most of whom are non-native - use. Native-speaker models with little attention paid to communication in the real world the learners will face is not optimal. A native-speaker model that ignores the Taiwanese businessman going to Korea, the young student planning to travel in Central Europe, the tech guy who talks to co-workers in India or young person who might not encounter native speakers often puts them at a disadvantage and is often the reason why good students in class, or even chatting with native speakers informally, hits a brick wall with other non-native speakers. This attitude, to be short, must change.

So what can we do?

Get training in how to teach ELF, and teach it if it fits your context (which it probably does). And let your students know why. Let them know that, in fact, as a native speaker you are not always an optimal model, and that learning by working with the English of non-native speakers is in many ways just as helpful or more helpful to them than only dealing with you.

School owners are often dismissive of foreign teacher concerns

This, I would like to emphasize, is not a problem with my employers. We are listened to and our opinions respected and considered and, often, acted on. I appreciate that a lot. It's why I continue to work for them. However, I can't say that's true for most, or even many, schools in Taiwan. Whether locally run or not - though most are run locally - there seems to be an unspoken but clear lack of respect for the sentiments of teachers, however correct or convincing they may be. (That's not to say such sentiments are always correct or convincing). Six-day workweeks, crazy hours and a lack of communication - or outright lying - driving high turnover, while the boss complains about high turnover? Low pay making it hard to hire good people? Textbooks that are required but not very good leading to poorer teaching?

All of these are valid concerns that are often dismissed by school administration, even at the "better" schools.

So, trying to bring up native speakerism is likely to get you about as far, if even that far, when opening such conversations. If they don't care that you're warning them that systemic problems in how they treat employees is the direct cause of high turnover, then they won't care about this.

So what can we do?

Change jobs. I feel like if the opportunity arose, I could bring this up at either of my workplaces without consequences, and be listened to. Try to find that kind of work. If your school is one where teachers and staff share resources and interesting articles, passing around an article on the issue may also have some awareness-raising effect, as well.

Other teachers will defend native speakerism

This is honestly the most aggravating to me, and I am sure that if this post makes the rounds among other expats that there will be blowback along exactly these lines. Whatever. I'll say it anyway.

I've heard it all - the same tired excuses that 'non-native speakers just don't know the language as well', 'this is the market, this is what the students want', 'you can't tell people whom they must hire, they can discriminate if they want and if someone doesn't like it they can find a different job', do you really want non-native speakers from India or the Philippines competing for your job, driving down wages?' and finally 'this is discrimination against native speakers, you think we're all know-nothings!'

Let's break all of these down:

Native speakers just don't know the language as well: covered it above

This is the market, this is what students want/employers can discriminate if they want: Due to lack of awareness and advertising for schools that preys on this. We can do better. In fact, research also shows the 'preference' among potential students is not as high as you would think. In any case, would you say "this is what the customer wants" as an excuse to discriminate based on gender, race, age or sexual orientation/gender identity? (If so, then you are pro-discrimination and I really don't know what to say except that there's a reason why such discrimination is illegal in most developed countries. It hurts members of those groups more than you realize, for very little reason. Customers, at times, have to be told when their requests are not reasonable.)

If someone doesn't like it they can find a different job: not if every single employer discriminates! Is it really okay to restrict the jobs available, or make no job at all available, to someone based on characteristics they can't change - and what your native language is happens to be such a characteristic, like age, race and orientation - for no reason other than to feed the prejudices of an uninformed clientele?

Do you really want "non-native" speakers from India or the Philippines competing for jobs and driving down wages? Well, I am a fan of government-mandated minimum wages at fair levels so the latter won't happen. As for competition, I welcome it. Competition makes for better product if it is fair. I am qualified. I have a decade of experience and a Delta, and will soon have a Master's in TESOL from a good school. The people who hire me - knowing what I cost - are not going to ditch me for someone who does not have such a background, and I would not want to work for anyone who would, or who thought that background was not necessary and just wanted to hire the cheapest taker. If those speakers - many of whom are actually native speakers or close enough to it - have similar credentials, then it is fair that we should compete. But it is fairly rare to have them at all, so I'm not that worried.

This is discrimination against native speakers, you think we're all know-nothings: This is the "what about WHITE HISTORY MONTH?!" of excuses used to defend native speakerism. I'm sorry, but it is. Many native speakers are not qualified to teach English. That does not mean those of us fighting native speakerism think none of them are. I'm a native speaker and I'm perfectly qualified to teach (but not because I'm a native speaker - in addition to it). I know that losing privilege feels like oppression, but I would beg those who think along these lines to really go back and consider what they are saying.

I have to say that I find these concerns worrying - in terms of advocating employment discrimination! - and unprofessional. If you don't have confidence in your ability to succeed in a wider employment pool, then why are you doing this job? Are you so afraid for your security that you want to shut others out to keep it? Is this even ethical? Is there not a whiff of wanting to cling to privilege about it?

So what can we do?

In terms of working on this attitude among other expats, simply making your points when the discussion comes up and sticking to them, doggedly raising awareness and not letting the privilege-clinging dominate the discussion, is all you can do until people start to listen.

I'm lucky, I can afford to have this attitude. Want to be lucky too? Upgrade yourself so you are not competing for low wages, but have the chance to work for people that recognize what you have to offer. Treat your profession like a profession, stop devaluing yourself. That's another thing you can do.

Trust me, if you actually take the time to, say, get a Delta or Master's, you won't want to work for people who would pay the lowest bidder $450/hour.

Employment laws are not enforced and there is no real union

This is tough too - in theory, Taiwan prohibits discrimination in employment based on race, gender, creed, sexual orientation etc.: basically the same way all other developed countries do. In theory, if you are fired (or not hired) for being (or not being) a certain race, you can sue, and you are supposed to win.

In practice, these laws are not enforced very well, if at all. There is no union of English teachers able to take action regarding this, and it's difficult for individuals to act without union representation. The three main issues facing unionization are that it is not popular in Taiwan (the workers' associations, which are unions in a way, don't quite act in the same way as we might imagine a union would), which also means that Taiwanese local teachers in private academies are not likely to join; it is hard to convince people scattered across many schools and employment types, many of whom are not planning to stay long-term or teach professionally to join; and that I have heard - correct me if I'm wrong - that only foreign workers with APRC or JFRV open work permits are allowed to unionize at all. If true, that means almost no English teachers in Taiwan are even eligible to legally unionize. Those that are are often so embedded in doing their own thing that it's hard to organize them (I admit to being somewhat guilty of this).

What that means is that if it's hard to get the government to act on discrimination based on race or gender, it will be even harder to get them to act based on native speakerism. Even if we get the employment laws for foreign teachers changed, there is no guarantee the new laws would be enforced.

So what can we do?

Unionize, or at least support the effort. Good luck with that. I told you this would be hard to fight. Set a precedent by fighting discrimination in other forms, such as that based on race, gender or age, so when you are ready and able to fight native speakerism, pushing back against discrimination and actually winning won't be a novel concept. Getting a more diverse teaching staff in schools will also speed up the acceptance that not all "good" English teachers look a certain way - a prejudice that is tied to native speakerism.

It's hard to advocate for "good teachers with credentials and experience regardless of native language" when credentials and experience aren't necessary in the first place, and learners are often unaware of this

This is another thing that aggravates me in Taiwan, although I do love this country with a ferocity I didn't think possible (and I am not a naturally patriotic person). There is a stunning lack of professionalism in many fields - my other bugbear is the journalistic standards of local media - English teaching not least among them.

I have said that I do think there is a place for inexperienced, even unqualified, new teachers in the industry. I can't be too hard on them, I used to be one. However, I do feel it ought to involve gradually increasing responsibility at an employer that provides good quality training along the way, with an internationally recognized certification eventually required.

That is not what happens in Taiwan, by a long shot.

If it is already considered acceptable to hire a fresh college grad with no relevant experience or credential, give him some materials (if you do even that), maybe let him observe a few classes and then have him go for it, with no attention paid to further training (or further quality training), then it will be quite difficult to convince schools, learners and teachers that in fact quality matters. It will be a battle just to dismantle the notion that teaching is an inborn talent - it is only in very rare circumstances - and to persuade people that experience without training isn't worth a fraction of what the two in tandem are worth.

So, convincing employers that, yes, a non-native speaker must have a very high level of English, but also that there are other qualities that also matter that make it possible for a non-native speaker teacher to teach just as well as a native speaker, is an uphill battle when they don't think those qualities are important even in native speakers.

So what can we do?

Raise awareness among your learners about what goes into teaching well. When they ask you for advice, tell them that they shouldn't be looking to continue their education with "a native speaker" per se, but a qualified, experienced teacher with good training. Tell them straight up that being a native speaker does not make one an automatically qualified language teacher, and advise them to aim higher.

Along with this, advocate for more training available in Taiwan. I did an entire Delta from Taiwan, but as it stands now there are no other strong, internationally-recognized pre-service or basic credentials available here. You have to leave the country for any such face-to-face credential (and, in fact, such credentials are worth little if they do not include practical experience). The more people who have training there are in the market, the more awareness about the importance of training there will be. Fun side effect: higher wages (at least one would hope) if starting a job with some training were the norm.

Foreigners don't teach "differently" and aren't "more fun" because of "culture"

This seems like an unrelated point, but bear with me.

Another excuse I often hear from learners about why they want native speakers isn't about being a native speaker at all - they think foreigners, Westerners specifically, are more "fun" and our classes are more "exciting". Often, they think that this is because our educational system and culture are "different". In some cases they mean "better", in others they mean "fine for after-school English class but in Real School Confucius-like stone-faced teachers who teach to the test as they give you more tests is still the way to go, and we are merely after-class entertainment.

Some may even think the 'fun' comes with a lack of training, as though training teaches a teacher to be boring.

Often this is pegged on the West just being fundamentally different. It is, in some ways (but hey I took boring classes and had tests too).

The truth is, though, that an untrained teacher is usually the more boring one, relying on old tropes of what a teacher does rather than more updated, modern pedagogical principles. The untrained teacher is more likely to fall back on drills, repetition, quizzes, worksheets, lecture-mode teaching, arduous and torturous (and not very useful) top-heavy presentations of grammar or other concepts, and maybe a few games here and there. When they are not boring, they rely on personality to get by (I was once guilty of this and perhaps from time to time still am when I get lazy - I do have the personality for it).

This is true no matter your cultural or national origin, let alone your native language. And yet it's used as the reason why a learner wants - or a school thinks a learner wants - a 'foreign English teacher' which really means a 'Western English teacher' which equates, generally, to a native speaker. It may be a way of asking for a native speaker without saying so directly.

So what can we do?

When you hear a learner talk about wanting a 'fun' class taught by a foreigner - or any other variation of the "foreigners are fun!" sentiment, counter it gently. A well-trained Taiwanese teacher can be just as 'fun' and an average native speaker teacher can be quite boring - it's experience and training that make a class better.

This introduces the concept of professional background, rather than national origin, being the key factor in a good teacher, which paves the way for acceptance of non-native teachers as just as able to teach a 'fun' or interesting class as native-speaking ones.

Language teacher training in Asia is not what it could be

Of course, going along with all of this is the need to better train local non-native speaker teachers in Taiwan. This is, in fact, a region-wide problem if not larger. It seems that non-native speaker local teachers are trained based on outdated or unsound principles, as friends of mine who have been through language teaching Master's programs say the pedagogical side often is neglected in favor of the Applied Linguistics side. If we want learners to accept that non-native speaker teachers can be just as qualified to lead a class as native-speaker ones, we need to do something about this, so that local non-native speaker teachers have more modern, principled teacher training.

So what can we do?

Very little, unless you yourself are a PhD, join the academic faculty at a school that offers a Master's in TESOL or other language teaching field (Applied Linguistics, Teaching Chinese as a Foreign Language, Applied Foreign Languages etc.) and push the school to modernize, which in Taiwan I know often is a losing battle. We can all stand to go out and get more training to raise the overall level of quality of English teaching, and we can push for an internationally-recognized teaching certification program (I don't want to say CELTA or Trinity, but if not them, at least something like them) to be offered in Taiwan so more non-native speaker teachers have a chance to attend. You can work to become the sort of person who would be qualified to be a tutor in such a course.

Those fighting native speakerism globally often have a blind spot

The final issue isn't so much what Taiwan can do, but a criticism of a lot of the dialogue internationally on how to fight native speakerism. These articles often have massive blind spots when it comes to Asia: they assume non-native speaker teachers can get visas: this is often not the case in Asia - if not Taiwan, then China and South Korea do have these restrictions, meaning that calling out discrimination where you see it and writing to schools with discriminatory ads is not a workable strategy.

They also tend to take as the default employers that are either within the formal education system (such as working in a public school) or are under the auspices of a government (such as British Council or IELTS), which are bound by certain professional and ethical standards that you can call upon when fighting native speakerism. That doesn't work when most employers are buxibans (private language academies) run by businesspeople, not educators, who run businesses, not schools, and who aren't, honestly, beholden to any professional or ethical standards at all, if they are even aware such standards exist in English teaching.

They often cite a "four week intensive course" as "the minimum qualification" to teach (and note that it is not sufficient in the long term, which is true). In Asia, however, this is generally not the case. In fact, in Taiwan if you have taken that course - they mean CELTA by the way - you are actually ahead of the game. The minimum qualification to teach is nothing at all. So advice that takes having something like CELTA as the minimum requirement to work is not helpful.

This needs to change - I don't mean to divide teachers, but it is dishonest to pretend these differences do not exist.

I wish I had better suggestions for how to deal with the situation we have, rather than the situation most common advice addresses. Unfortunately, in the ELT industry as we experience it in Taiwan, there is little we can do except push back gently when the issue comes up, raise the issue when it is pertinent, raise awareness when the opportunity arises, and improve ourselves via quality training and experience to bring the industry overall to a higher standard, which will hopefully bring with it more up-to-date ethical standards on the non-native speaker teacher issue.

However, something about this really ought to be said. First, a primer in what 'native speakerism' is.

None of this is new - there is a whole organization dedicated to fighting native speakerism. But, to get into why it's difficult to fight in Taiwan, I feel the groundwork needs to be laid.

Native speakerism is a global issue - preconceived notions about what makes a 'teacher' due to a lack of general training in ELT issues (which is fair - not everyone is going to have a basic knowledge of education theory) causes learners to believe that native speaker teachers are superior and schools advertising the usually (but not always) white, Western faces of the teachers with correspondingly high tuition preys on notions of 'prestige' in teaching. Learners then request native speaker teachers, leading schools to then discriminate against non-native speaker teachers in hiring, and blame it on "the market" - a market which they helped create. It doesn't help that a horrifying lack of professional standards makes it possible to get a teaching job with no qualifications or experience to speak of other than being a native speaker, and that the owners of language schools are often local businesspeople, not educators, and do not know themselves what to look for in a quality teacher - they too boil it down to "native speaker, looks the part, cheaper than a trained teacher, you're hired."

One can add to that a big fat dollop of outdated assumptions of what it means to be a "non-native speaker". People who don't know better will insist that "non-native speakers can't possibly know all of the idiomatic language, rare collocations and modern usages of English, they'll teach a more textbook English", but that assumes quite a bit about a native speaker. An Egyptian woman who spent the first ten years of her life in Cairo, but then moved to England and had lived there ever since, for example, would speak at a level so close to native that you would not know she wasn't a native speaker, and would have more knowledge of British idiomatic language than I do. How is she less of a 'native speaker' than I am? A Taiwanese student who went through an entire school curriculum at TES or TAS, who might speak flawlessly - you might mistake her for an Asian woman from the West - is she a native speaker? My own grandfather grew up in Greece and moved to the US in elementary school. His native languages were Western Armenian - there are a genocide and two escapes in that story - and Greek. To hear him talk now you would never think of him as anything other than a native speaker of English. Is he? Why do you assume all native speakers speak an imperfect, textbook-y or even 'foreign accented' (again, whatever that means) English?

And that's not even getting into issues of cultural or linguistic imperialism and the notion that only "native speaker English" (whatever that means) is "good enough", or that there is something wrong with local varieties of English!

What really goes into teaching well is, of course, a high level or native-like level of English: something many non-native speakers attain, as well as sound training (whether it confers a credential or not - the piece of paper is not the point, though it's hard to gauge the quality of non-credentialed training) and increasing levels of responsibility through experience. Some level of basic talent or affinity for teaching helps. Research agrees: if the level of English is sufficient and the teaching is pedagogically sound, the first language of the teacher makes no difference.

I find this a very convincing set of arguments for doing away with discrimination based on first language in language teaching, and yet the problem persists in Taiwan. Why?

The law is outdated

There are conflicting accounts of what the laws actually say. Most non-native speaker teachers in Taiwan are Taiwanese themselves, students on a student visa that allows work, or other foreign residents married to locals. A few have Master's degrees and therefore can be hired for any job. It is unclear whether, legally, visas for non-native speaker teachers who come to Taiwan simply to teach can be procured by schools however. I have been told "no", I have been sent unclear links with confusing language, I have been told such visas have been successfully issued, although every example seems to be of a white European. I have been told English must be the 'official language' of the country of origin, but the US has no official language, and plenty of countries people don't think of as English-speaking, such as Nigeria and India, do have English as an 'official language'.

However, I have also heard firsthand accounts of non-native speaker, non-Taiwanese foreigners trying and failing to get a visa to teach English because they held the "wrong" passport (not from Canada, the US, Ireland, the UK, South Africa, Australia or New Zealand). So, let's just say that the law is unclear but if you are not a native speaker, and do not have another pathway to a job that doesn't require a school-sponsored visa, and lack a Master's degree, that it is likely to be difficult for you to procure a visa to work in Taiwan.

This is in direct contradiction to research on effective teaching, and yet it remains a problem. When it is difficult to get a school to even offer a job to someone they know they may not be able to get a visa for, it makes sense that schools would go for candidates for whom visas would be promptly issued.

So what can we do?

Honestly, I have no idea. You can lobby the government - good luck with that. You can write an editorial - nobody will read it. You can try to raise awareness among locals inclined to do something about it, but so few are even if they agree with you. If you ever do find yourself with the right kind of guanxi in the government, this would be a great place to use it to bend someone's ear. For now, however, I'm at a loss.

It's hard to know which schools would not discriminate, given the choice

It's very difficult to know what a school would do if it didn't have this potential legal hurdle to hiring non-native speakers and very difficult to fight, as it requires a change in the law.

My various employers, for example, are all good people. They're sensible and they have some foundational knowledge of the qualities needed in a good teacher. I do not want to think that, given the chance to hire a non-native speaker teacher who would need a visa, that they would discriminate. However, due to the confusion and difficulty inherent in the law, it is hard to be sure. How can I talk to my employer about a problem if I don't even know if it exists, or if it only exists hypothetically?

In my school I noticed an advertising sign-listicle sort of things ("10 reasons to study with us!" but at least it didn't have something like "#8 will shock you!") where one of the items was "Canadian, British and American teachers: the world of IELTS comes to you!" - what does that mean exactly? Is that pro-native-speakerism? Would they discriminate against a talented, native-like and qualified non-native speaker if given the chance to hire one? It's hard to say. It's just an item on a list tacked to the wall, and there's no way to test the sincerity of it. How does one even bring that up?

This makes it difficult to have these conversations with employers - note conversations, not confrontations or arguments - when you can't really know where they stand. When perhaps they themselves don't know where they stand. It's hard to push the issue further or raise awareness.

So what can we do?

One of the core messages of TEFL Equality Advocates is for native speaker teachers to use their privilege to help change the system: not applying to work at schools that discriminate, withdrawing one's application from a school that indicates that it discriminates later in the process, and writing to such schools to tell them why (in gentler words, of course).

It's difficult to do that when you can't know if a school would discriminate if they didn't have to by (very confusing) law. What you can do, though, is bring it up if the opportunity arises and try to gauge your school's attitude towards native speakerism, and take it from there.

The 'native speaker' model is still seen as the best, or only, choice

This is a massive problem in a world where ELF (English as a Lingua Franca) is the English that most English speakers - most of whom are non-native - use. Native-speaker models with little attention paid to communication in the real world the learners will face is not optimal. A native-speaker model that ignores the Taiwanese businessman going to Korea, the young student planning to travel in Central Europe, the tech guy who talks to co-workers in India or young person who might not encounter native speakers often puts them at a disadvantage and is often the reason why good students in class, or even chatting with native speakers informally, hits a brick wall with other non-native speakers. This attitude, to be short, must change.

So what can we do?

Get training in how to teach ELF, and teach it if it fits your context (which it probably does). And let your students know why. Let them know that, in fact, as a native speaker you are not always an optimal model, and that learning by working with the English of non-native speakers is in many ways just as helpful or more helpful to them than only dealing with you.

School owners are often dismissive of foreign teacher concerns

This, I would like to emphasize, is not a problem with my employers. We are listened to and our opinions respected and considered and, often, acted on. I appreciate that a lot. It's why I continue to work for them. However, I can't say that's true for most, or even many, schools in Taiwan. Whether locally run or not - though most are run locally - there seems to be an unspoken but clear lack of respect for the sentiments of teachers, however correct or convincing they may be. (That's not to say such sentiments are always correct or convincing). Six-day workweeks, crazy hours and a lack of communication - or outright lying - driving high turnover, while the boss complains about high turnover? Low pay making it hard to hire good people? Textbooks that are required but not very good leading to poorer teaching?

All of these are valid concerns that are often dismissed by school administration, even at the "better" schools.

So, trying to bring up native speakerism is likely to get you about as far, if even that far, when opening such conversations. If they don't care that you're warning them that systemic problems in how they treat employees is the direct cause of high turnover, then they won't care about this.

So what can we do?

Change jobs. I feel like if the opportunity arose, I could bring this up at either of my workplaces without consequences, and be listened to. Try to find that kind of work. If your school is one where teachers and staff share resources and interesting articles, passing around an article on the issue may also have some awareness-raising effect, as well.

Other teachers will defend native speakerism

This is honestly the most aggravating to me, and I am sure that if this post makes the rounds among other expats that there will be blowback along exactly these lines. Whatever. I'll say it anyway.

I've heard it all - the same tired excuses that 'non-native speakers just don't know the language as well', 'this is the market, this is what the students want', 'you can't tell people whom they must hire, they can discriminate if they want and if someone doesn't like it they can find a different job', do you really want non-native speakers from India or the Philippines competing for your job, driving down wages?' and finally 'this is discrimination against native speakers, you think we're all know-nothings!'

Let's break all of these down:

Native speakers just don't know the language as well: covered it above

This is the market, this is what students want/employers can discriminate if they want: Due to lack of awareness and advertising for schools that preys on this. We can do better. In fact, research also shows the 'preference' among potential students is not as high as you would think. In any case, would you say "this is what the customer wants" as an excuse to discriminate based on gender, race, age or sexual orientation/gender identity? (If so, then you are pro-discrimination and I really don't know what to say except that there's a reason why such discrimination is illegal in most developed countries. It hurts members of those groups more than you realize, for very little reason. Customers, at times, have to be told when their requests are not reasonable.)

If someone doesn't like it they can find a different job: not if every single employer discriminates! Is it really okay to restrict the jobs available, or make no job at all available, to someone based on characteristics they can't change - and what your native language is happens to be such a characteristic, like age, race and orientation - for no reason other than to feed the prejudices of an uninformed clientele?

Do you really want "non-native" speakers from India or the Philippines competing for jobs and driving down wages? Well, I am a fan of government-mandated minimum wages at fair levels so the latter won't happen. As for competition, I welcome it. Competition makes for better product if it is fair. I am qualified. I have a decade of experience and a Delta, and will soon have a Master's in TESOL from a good school. The people who hire me - knowing what I cost - are not going to ditch me for someone who does not have such a background, and I would not want to work for anyone who would, or who thought that background was not necessary and just wanted to hire the cheapest taker. If those speakers - many of whom are actually native speakers or close enough to it - have similar credentials, then it is fair that we should compete. But it is fairly rare to have them at all, so I'm not that worried.

This is discrimination against native speakers, you think we're all know-nothings: This is the "what about WHITE HISTORY MONTH?!" of excuses used to defend native speakerism. I'm sorry, but it is. Many native speakers are not qualified to teach English. That does not mean those of us fighting native speakerism think none of them are. I'm a native speaker and I'm perfectly qualified to teach (but not because I'm a native speaker - in addition to it). I know that losing privilege feels like oppression, but I would beg those who think along these lines to really go back and consider what they are saying.

I have to say that I find these concerns worrying - in terms of advocating employment discrimination! - and unprofessional. If you don't have confidence in your ability to succeed in a wider employment pool, then why are you doing this job? Are you so afraid for your security that you want to shut others out to keep it? Is this even ethical? Is there not a whiff of wanting to cling to privilege about it?

So what can we do?

In terms of working on this attitude among other expats, simply making your points when the discussion comes up and sticking to them, doggedly raising awareness and not letting the privilege-clinging dominate the discussion, is all you can do until people start to listen.

I'm lucky, I can afford to have this attitude. Want to be lucky too? Upgrade yourself so you are not competing for low wages, but have the chance to work for people that recognize what you have to offer. Treat your profession like a profession, stop devaluing yourself. That's another thing you can do.

Trust me, if you actually take the time to, say, get a Delta or Master's, you won't want to work for people who would pay the lowest bidder $450/hour.

Employment laws are not enforced and there is no real union

This is tough too - in theory, Taiwan prohibits discrimination in employment based on race, gender, creed, sexual orientation etc.: basically the same way all other developed countries do. In theory, if you are fired (or not hired) for being (or not being) a certain race, you can sue, and you are supposed to win.

In practice, these laws are not enforced very well, if at all. There is no union of English teachers able to take action regarding this, and it's difficult for individuals to act without union representation. The three main issues facing unionization are that it is not popular in Taiwan (the workers' associations, which are unions in a way, don't quite act in the same way as we might imagine a union would), which also means that Taiwanese local teachers in private academies are not likely to join; it is hard to convince people scattered across many schools and employment types, many of whom are not planning to stay long-term or teach professionally to join; and that I have heard - correct me if I'm wrong - that only foreign workers with APRC or JFRV open work permits are allowed to unionize at all. If true, that means almost no English teachers in Taiwan are even eligible to legally unionize. Those that are are often so embedded in doing their own thing that it's hard to organize them (I admit to being somewhat guilty of this).

What that means is that if it's hard to get the government to act on discrimination based on race or gender, it will be even harder to get them to act based on native speakerism. Even if we get the employment laws for foreign teachers changed, there is no guarantee the new laws would be enforced.

So what can we do?

Unionize, or at least support the effort. Good luck with that. I told you this would be hard to fight. Set a precedent by fighting discrimination in other forms, such as that based on race, gender or age, so when you are ready and able to fight native speakerism, pushing back against discrimination and actually winning won't be a novel concept. Getting a more diverse teaching staff in schools will also speed up the acceptance that not all "good" English teachers look a certain way - a prejudice that is tied to native speakerism.

It's hard to advocate for "good teachers with credentials and experience regardless of native language" when credentials and experience aren't necessary in the first place, and learners are often unaware of this

This is another thing that aggravates me in Taiwan, although I do love this country with a ferocity I didn't think possible (and I am not a naturally patriotic person). There is a stunning lack of professionalism in many fields - my other bugbear is the journalistic standards of local media - English teaching not least among them.

I have said that I do think there is a place for inexperienced, even unqualified, new teachers in the industry. I can't be too hard on them, I used to be one. However, I do feel it ought to involve gradually increasing responsibility at an employer that provides good quality training along the way, with an internationally recognized certification eventually required.

That is not what happens in Taiwan, by a long shot.

If it is already considered acceptable to hire a fresh college grad with no relevant experience or credential, give him some materials (if you do even that), maybe let him observe a few classes and then have him go for it, with no attention paid to further training (or further quality training), then it will be quite difficult to convince schools, learners and teachers that in fact quality matters. It will be a battle just to dismantle the notion that teaching is an inborn talent - it is only in very rare circumstances - and to persuade people that experience without training isn't worth a fraction of what the two in tandem are worth.

So, convincing employers that, yes, a non-native speaker must have a very high level of English, but also that there are other qualities that also matter that make it possible for a non-native speaker teacher to teach just as well as a native speaker, is an uphill battle when they don't think those qualities are important even in native speakers.

So what can we do?

Raise awareness among your learners about what goes into teaching well. When they ask you for advice, tell them that they shouldn't be looking to continue their education with "a native speaker" per se, but a qualified, experienced teacher with good training. Tell them straight up that being a native speaker does not make one an automatically qualified language teacher, and advise them to aim higher.

Along with this, advocate for more training available in Taiwan. I did an entire Delta from Taiwan, but as it stands now there are no other strong, internationally-recognized pre-service or basic credentials available here. You have to leave the country for any such face-to-face credential (and, in fact, such credentials are worth little if they do not include practical experience). The more people who have training there are in the market, the more awareness about the importance of training there will be. Fun side effect: higher wages (at least one would hope) if starting a job with some training were the norm.

Foreigners don't teach "differently" and aren't "more fun" because of "culture"

This seems like an unrelated point, but bear with me.

Another excuse I often hear from learners about why they want native speakers isn't about being a native speaker at all - they think foreigners, Westerners specifically, are more "fun" and our classes are more "exciting". Often, they think that this is because our educational system and culture are "different". In some cases they mean "better", in others they mean "fine for after-school English class but in Real School Confucius-like stone-faced teachers who teach to the test as they give you more tests is still the way to go, and we are merely after-class entertainment.

Some may even think the 'fun' comes with a lack of training, as though training teaches a teacher to be boring.

Often this is pegged on the West just being fundamentally different. It is, in some ways (but hey I took boring classes and had tests too).

The truth is, though, that an untrained teacher is usually the more boring one, relying on old tropes of what a teacher does rather than more updated, modern pedagogical principles. The untrained teacher is more likely to fall back on drills, repetition, quizzes, worksheets, lecture-mode teaching, arduous and torturous (and not very useful) top-heavy presentations of grammar or other concepts, and maybe a few games here and there. When they are not boring, they rely on personality to get by (I was once guilty of this and perhaps from time to time still am when I get lazy - I do have the personality for it).

This is true no matter your cultural or national origin, let alone your native language. And yet it's used as the reason why a learner wants - or a school thinks a learner wants - a 'foreign English teacher' which really means a 'Western English teacher' which equates, generally, to a native speaker. It may be a way of asking for a native speaker without saying so directly.

So what can we do?

When you hear a learner talk about wanting a 'fun' class taught by a foreigner - or any other variation of the "foreigners are fun!" sentiment, counter it gently. A well-trained Taiwanese teacher can be just as 'fun' and an average native speaker teacher can be quite boring - it's experience and training that make a class better.

This introduces the concept of professional background, rather than national origin, being the key factor in a good teacher, which paves the way for acceptance of non-native teachers as just as able to teach a 'fun' or interesting class as native-speaking ones.

Language teacher training in Asia is not what it could be

Of course, going along with all of this is the need to better train local non-native speaker teachers in Taiwan. This is, in fact, a region-wide problem if not larger. It seems that non-native speaker local teachers are trained based on outdated or unsound principles, as friends of mine who have been through language teaching Master's programs say the pedagogical side often is neglected in favor of the Applied Linguistics side. If we want learners to accept that non-native speaker teachers can be just as qualified to lead a class as native-speaker ones, we need to do something about this, so that local non-native speaker teachers have more modern, principled teacher training.

So what can we do?

Very little, unless you yourself are a PhD, join the academic faculty at a school that offers a Master's in TESOL or other language teaching field (Applied Linguistics, Teaching Chinese as a Foreign Language, Applied Foreign Languages etc.) and push the school to modernize, which in Taiwan I know often is a losing battle. We can all stand to go out and get more training to raise the overall level of quality of English teaching, and we can push for an internationally-recognized teaching certification program (I don't want to say CELTA or Trinity, but if not them, at least something like them) to be offered in Taiwan so more non-native speaker teachers have a chance to attend. You can work to become the sort of person who would be qualified to be a tutor in such a course.

Those fighting native speakerism globally often have a blind spot

The final issue isn't so much what Taiwan can do, but a criticism of a lot of the dialogue internationally on how to fight native speakerism. These articles often have massive blind spots when it comes to Asia: they assume non-native speaker teachers can get visas: this is often not the case in Asia - if not Taiwan, then China and South Korea do have these restrictions, meaning that calling out discrimination where you see it and writing to schools with discriminatory ads is not a workable strategy.

They also tend to take as the default employers that are either within the formal education system (such as working in a public school) or are under the auspices of a government (such as British Council or IELTS), which are bound by certain professional and ethical standards that you can call upon when fighting native speakerism. That doesn't work when most employers are buxibans (private language academies) run by businesspeople, not educators, who run businesses, not schools, and who aren't, honestly, beholden to any professional or ethical standards at all, if they are even aware such standards exist in English teaching.

They often cite a "four week intensive course" as "the minimum qualification" to teach (and note that it is not sufficient in the long term, which is true). In Asia, however, this is generally not the case. In fact, in Taiwan if you have taken that course - they mean CELTA by the way - you are actually ahead of the game. The minimum qualification to teach is nothing at all. So advice that takes having something like CELTA as the minimum requirement to work is not helpful.

This needs to change - I don't mean to divide teachers, but it is dishonest to pretend these differences do not exist.

I wish I had better suggestions for how to deal with the situation we have, rather than the situation most common advice addresses. Unfortunately, in the ELT industry as we experience it in Taiwan, there is little we can do except push back gently when the issue comes up, raise the issue when it is pertinent, raise awareness when the opportunity arises, and improve ourselves via quality training and experience to bring the industry overall to a higher standard, which will hopefully bring with it more up-to-date ethical standards on the non-native speaker teacher issue.

Tuesday, December 20, 2016

Greatest Hits from Brendan and Jenna Get Together: Live in Tainan 2007

So, thanks to work obligations, we found ourselves back in Tainan for the third time this year.

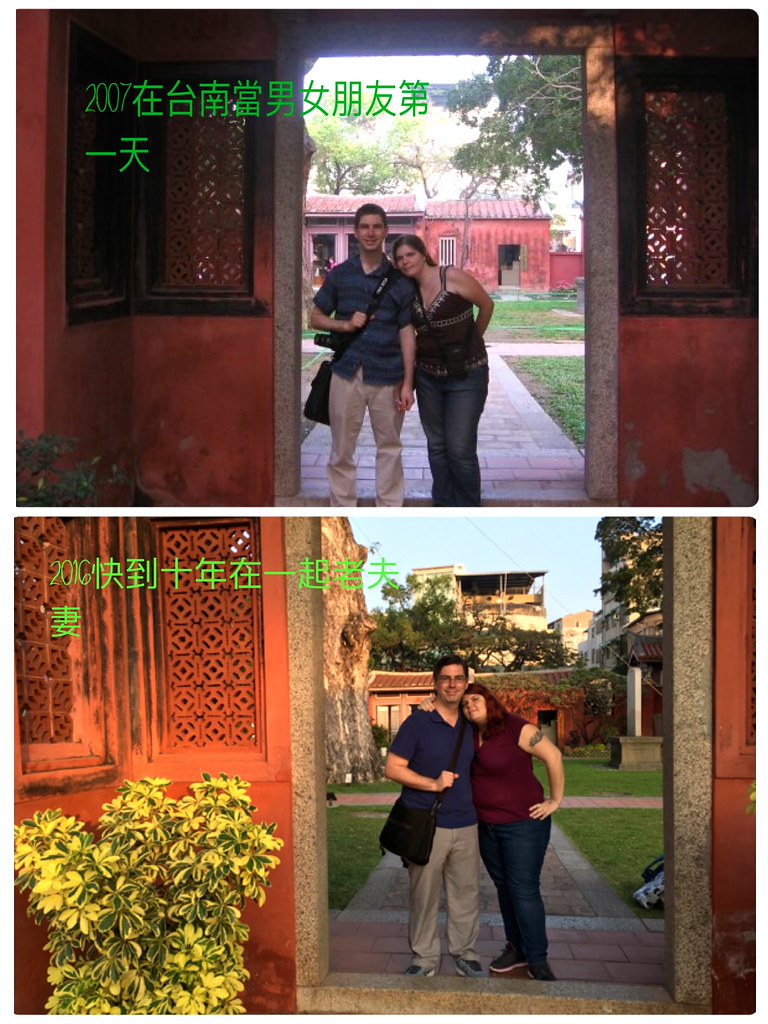

What I found sentimental about that, moreoso than over the summer, was that Brendan and I are nearing our 10th anniversary as a couple. As I mentioned in an earlier post, we got together in Tainan, and our very first picture together as a bona fide couple (rather than two very frustrated best friends who clearly liked each other) was taken at the Confucius Temple there.

That was on March 1st (or thereabouts) 2007, and as it is highly unlikely we'll be in Tainan on March 1st 2017 - though you never know, we could be sent back for work - this is about as close as we are likely to get to return to the city where we got together close to a major anniversary date.

So, of course we went back to the Confucius Temple and took the same picture again (above). I won't comment on how we've changed and how we haven't, I will note that ten years on, six of them as a married couple, we still have that undefinable spark. It may be a more comfortable warmth rather than, say, what happened last time which I am pretty sure entailed making out in the Confucius Temple - Confucius was surely not pleased - but it's there. Like the perfect teaming of a chaos and an order muppet. (I'm the Swedish Chef, if you must know).

So, I don't have much about Tainan to say in this post - you can read that in my posts from earlier this year (one is linked above, here's the other). What I do feel like talking about is how we went back and did a lot of the same things we did ten years ago - without really thinking about it. A few things have changed: we didn't know about the life-changing food combination that is ice cream served in half a melon available at Taicheng Fruit Store (泰成水果店) nor about Narrow Door Cafe (窄門咖啡) and I am fairly sure our favorite bar, Taikoo (太古), was not open yet.

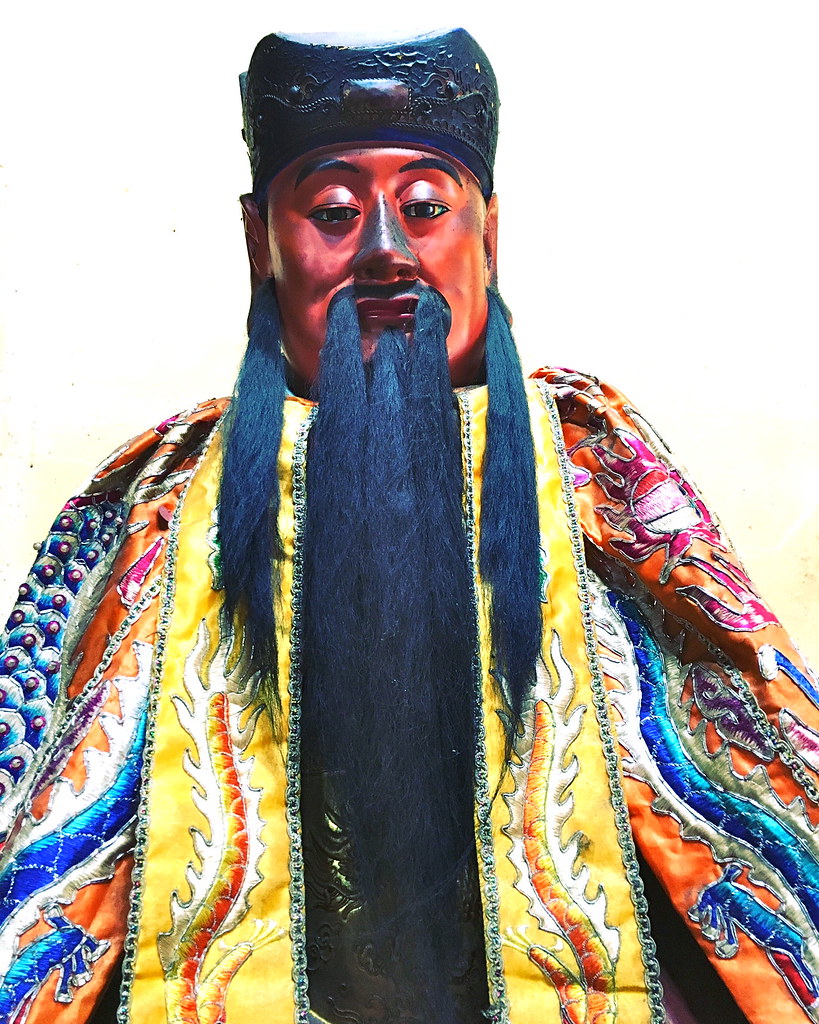

But coffee at Chihkan Towers just for the atmosphere? Confucius Temple? God of Hell Temple? Famous glutinous meat dumplings? Running into a temple parade? All the greatest hits from 2007 got played, and it was in fact very sentimental and lovely to re-live it like that, as Old Married People rather than Young Love. It's like dancing to the song you first danced to, if we danced, which we don't really.

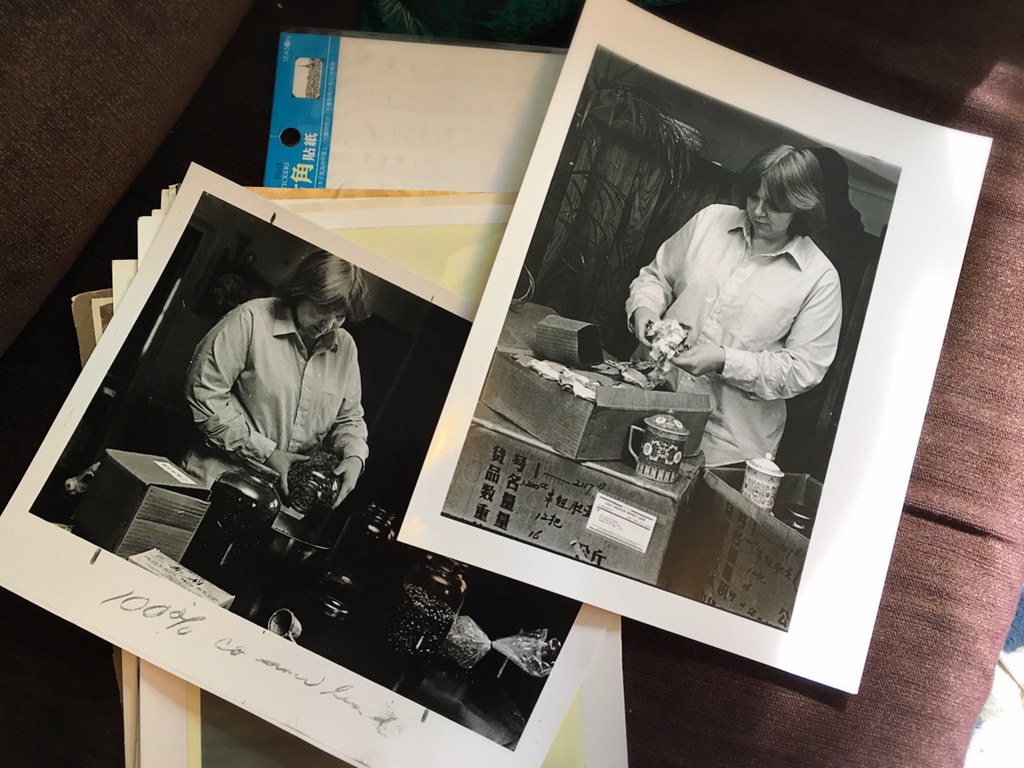

Perhaps I was also feeling sentimental because it's the holidays - my mom loved the holidays and also passed away around this time of year (actually almost two years ago exactly). I have been thinking, as I put together an album of her photos, how much she also liked old man's tea (老人茶 or laorencha - the title of this blog, though that's not the reason), and how sad I am that we never got to drink it together in Taiwan. So, I think a lot about family, relationships and life at this time of year.

|

| My mom in the early 1980s - I would have likely been a baby when this was taken. |

Anyway, enjoy some photos. This first one is one of the common areas in our hotel this time, called Goin Old House Bed and Breakfast (and also bar, on the first floor). The rooms are simple, clean and a little old-timey/traditional, with very modern bathrooms, which I appreciate. And it's extremely central.

Track 1 on Greatest Hits from Brendan and Jenna Get Together: Live in Tainan 2007, coffee at Chihkan Tower:

Track 2: Temple Parade (this happened in Anping in 2007 but at the God of War temple this time):

Track 3: Let's eat some meatballs (肉圓 - the famous ones by the God of War Temple):

Track 4: Wandering the Backstreets

Track 5: The God of Hell Temple (東嶽殿), but the murals weren't as visible this time:

Track 6: Backstreets, Refrain

Bonus Tracks: Narrow Door Cafe:

Bonus Track 2: Taicheng Fruit Store:

Bonus Track 3: Taikoo Bar

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)