Hey Taiwan residents - both foreign and local - do you have a refugee fund?

That is, personal savings or some other safety net that you are preparing in the event that a Chinese invasion of Taiwan forces you to leave?

I do. I don't want to leave, and would not do so unless I absolutely had to - we're not talking "the invasion is coming soon", we're talking "my house just got bombed, people are dying and I have nowhere to go." And I only mean that in the event that I am not a citizen: I don't owe my life to a country that won't even give me a passport. If I had obtained Taiwanese citizenship by that point, however, that's a different obligation and I would stay and fight.

The money I have set aside could be used as a down payment on property. If I don't need it, it will be part of my retirement fund. I could use it to pay off my student loans. There are a million other things I could do with it, but I may need it for this purpose and don't feel safe not having it available, so here we are.

Of course I'm very privileged that I'd even be able to leave (a lot of locals would not be) and that the money is there, but here's the thing.

I should not need to set aside money specifically for my escape from a free and developed democracy due to a highly possible invasion by a hostile foreign power. Nobody should have to.

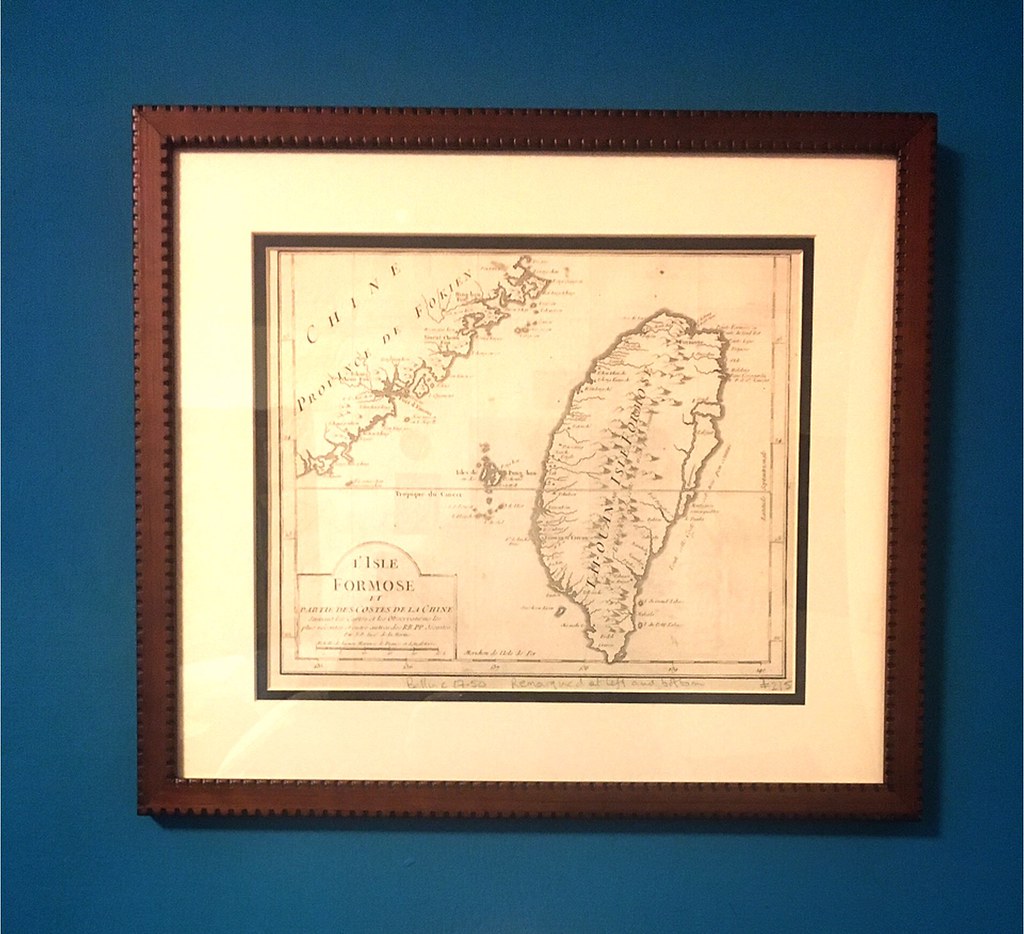

Not in a country that actively wants to exist in peace, and has no desire to start any wars with any other nation.

I should not need to wonder, quite pragmatically, whether the rest of the world will tolerate a brutal dictatorship violently annexing the world's 22nd largest economy, one of the US's top trading partners, with a population comparable to that of Australia which is free, basically well-run and friendly to other nations. I should not need to consider whether my decision to stay or go - and the money I need to do that - may well hinge on whether that help comes.

I'm reasonably sure all of my friends in Taiwan - local and foreign - can understand this.

I am not sure at all that my friends abroad do, though. I'm not sure especially if people I know in the US, Europe, Japan (all developed countries/regions, a group in which Taiwan also qualifies) and beyond are aware of what it's like to have a practical, non-insane notion that they might have 30 days' notice that their life and livelihood as they know it is about to be over. Where "getting out" and losing everything would be the better outcome, and how many more people (again, the population of Australia) might not even have that option.

So I still hear things like "oh but you don't want US help, it'd be just like Iraq or Syria, they'd wreck the place!" or "I don't want your city to become another Fallujah."

Do they understand that it is China who would turn Taipei into an East Asian Fallujah?

And that their and their governments' wishy-washy response to Chinese threats against Taiwan are a part of why I need to have this fund at all?

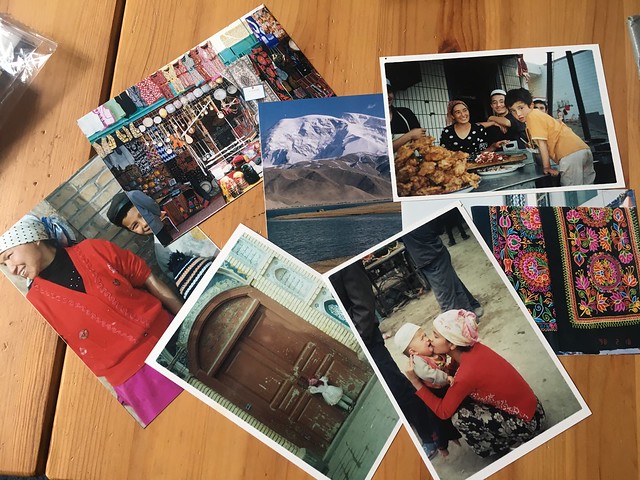

That they think they support peace, but in fact they'd leave us (foreign residents and Taiwanese both) to run or die in war? Do they understand what it would be like for Taiwan to be forcibly annexed by China? Do they understand that giving in and just surrendering to authoritarian rule - and the loss of very real and important freedom and human rights - is not an option? That there is no One Country, Two Systems?

Over the past few years I've come to realize that while at heart I want to be a dove, I can't. Sure, I agree that the US is a neo-imperialist murder machine. Fine. We suck. I won't even argue that we don't. We've done so much harm in the world.

But Taiwan is not Iraq. It's not Syria, it's not Iran or Afghanistan or Central America. It's just not. It's not even comparable. It has its own military and simply needs assistance (or the promise of it, to keep China from attempting an invasion). It has its own successful democratic government and rule of law (I mean...basically. Taiwan does okay.) There'd be no democracy-building or post-war occupation needed. It just needs friends. Big friends, who can tell the bully to back off.

So, y'know, I don't give a crap anymore about anyone's "but the US is evil!" I just don't. Y'all are not wrong, but it simply does not matter. China wants to wreck this country, not the US. China's the invader and (authoritarian) government-builder, not the US. China will turn their guns and bombs on Taiwanese, not the US.

And if you're not the one who has all those missiles pointed at them, you're not the one with lots of friends who could lose everything (including their lives), or lose everything yourself, and you're not the one actively building a refugee fund to escape an otherwise peaceful, developed and friendly country, then you can take all that "but the US is evil!" and shove it. This is a real world situation where we don't exactly have the luxury of choice in who stands by us. There isn't a "better option". There just...isn't.

Unless you think a friendly, open and vibrant democracy being swallowed by a massive dictatorship and losing all access to human rights is totally fine, or that having a refugee fund when living in said open democratic nation is normal.

It's not normal. My refugee fund should not have to exist. Please understand this.