|

| Taiwan, have a look in the mirror. You are just as worthy of tourism as Vietnam. |

Brendan and I spent lunar new year in Vietnam - as anyone who has lived in Taiwan knows, if you don't have family to visit, it's about as boring as Christmas Day must be for foreigners in the US with nowhere to go. We usually skip town, and have only avoided Vietnam so far because we were worried that it would be more difficult to visit because they also have a lunar new year holiday (Tet, which you know if you've heard of the Tet Offensive, which I hope you have). There were some Tet-related crowds and complications, however, overall I'd say our fears were unfounded.

And that's where my regular travel post about Vietnam ends, because frankly, you can read all you want to about it anywhere else. I actually want to talk about Taiwan, then show you some pictures from Vietnam for a related reason. In any case, Vietnam is entrenched on the tourist map, with hordes of visitors from around the world coming every day. You might even say Vietnam is the new Thailand (but hasn't quite reached the levels of "Foreigner Playland" that Thailand seems to have, or Bali, for that matter). That's not necessarily always a bad thing, but overall you don't need my input - though I'll say one thing anyway: skip the lots-of-hotels-and-so-so-beach by the highway at Nha Trang and find yourself a quieter beach (we really liked Jungle Beach, well to the north of Nha Trang). We transferred from our ride from Jungle Beach to the bus there, and even in that short glimpse I was deeply unimpressed with what was essentially a tourist drag on a strip of sand.

That's it, though. What I want to talk about is more closely related to Taiwan. It's nothing new - other people have made the same arguments - I possibly have as well, and simply forgotten - but I'll say it anyway.

Tourists who go to Vietnam - and there are many, from every continent - are likely to come away thinking something along the lines of "wow, Vietnam is a great place in Asia for lively street life, great street food, architecture and interesting night markets! Such a cool country! Really some of the best Asia has to offer!"

The compliment would be warranted - Vietnam is truly great. We enjoyed ourselves immensely. But I couldn't help but think as these masses of folks of all different colors, creeds and national origins - though let's be honest, they were mostly white or Chinese - wandered through Hoi An's packed night market oohing and aahing over the food stalls and shopping opportunities - that Taiwan has these things too.

In fact, I think I may have exclaimed to no one in particular at some point, "hey! Taiwan has all of this too, but so few people come!"

OK, this is not entirely fair: Taiwan has a fairly bustling tourism industry, mostly made up of visitors from nearby Asian countries, and it has been on the rise since the dreaded Chinese tour groups finally, mercifully left. But it's really a small slice of the pie compared to the people pouring into Vietnam, and with noticeably fewer Westerners or anyone from any other continent. That feels so rare in Taiwan - Western backpackers - that even though I hosted one briefly (we knew each other from the old Lonely Planet Thorn Tree - remember that? I was channamasala), when I ran into some at Yonghe Soy Milk I was genuinely surprised.

The compliment would be warranted - Vietnam is truly great. We enjoyed ourselves immensely. But I couldn't help but think as these masses of folks of all different colors, creeds and national origins - though let's be honest, they were mostly white or Chinese - wandered through Hoi An's packed night market oohing and aahing over the food stalls and shopping opportunities - that Taiwan has these things too.

In fact, I think I may have exclaimed to no one in particular at some point, "hey! Taiwan has all of this too, but so few people come!"

OK, this is not entirely fair: Taiwan has a fairly bustling tourism industry, mostly made up of visitors from nearby Asian countries, and it has been on the rise since the dreaded Chinese tour groups finally, mercifully left. But it's really a small slice of the pie compared to the people pouring into Vietnam, and with noticeably fewer Westerners or anyone from any other continent. That feels so rare in Taiwan - Western backpackers - that even though I hosted one briefly (we knew each other from the old Lonely Planet Thorn Tree - remember that? I was channamasala), when I ran into some at Yonghe Soy Milk I was genuinely surprised.

Few people not from the region come to Taiwan, so few can leave thinking "wow, Taiwan is so cool - lively street life, vibrant night markets, street food, old buildings, traditional culture - really a great destination!" All these distinctions that could be heaped on Taiwan are heaped on Vietnam.

I could go into the reasons why this is, but will keep it brief - in the end it comes down to China trying to erase Taiwan as a unique entity in the global consciousness, and the Taiwanese government doing a poor job of promoting tourism outside of Asia. I could write a lot more about this, but I'll save that for another post.

The central question, in fact, is this:

Part of me doesn't want this to change. I would very much like to keep Taiwan to myself. Possibly, because I am a curmudgeonly old git, I would see these backpackers I am now lamenting a dearth of, should they finally descend on Taiwan, and basically think GET OFF MY LAWN. I rather like living in an undiscovered gem of a country that isn't packed with the banana pancake set, or the wealthier set that includes their parents. I like that local culture is wonderfully uncommodified. I like that Lishan, my favorite mountain town, is a gritty little place where the most interesting things to do are read books and enjoy the view as you eat fresh fruit. All of the things that can make Taiwan annoying and inaccessible (like having to rent a car to go anywhere, and never being quite sure when temple festivals are) also make it wonderful and authentic.

It's uncharitable, but I must acknowledge that aspect of my thinking. If we did get all these tourists, we could expect every town of interest - Sanxia, Beipu, Daxi, Tainan, Lugang, Jiaoxi, Hualien, Kenting, Jiufen, Jinguashi and more - they'd all be exponentially more crowded than they already are (which is pretty damn crowded). This part is obvious, but what that means is that more businesses selling crap souvenirs - as though there aren't enough already - and other things aimed entirely at tourists will start opening, and soon enough what is now confined to a single awful lane in Jiufen will be found in every one of these towns. I do not relish that. I make no secret of my dislike for tour buses - I understand why people take them, but I always try to run ahead of the crowd of people about to be disgorged, and they do clog up the roads.

This is also uncharitable of me: what makes me so special that I get to enjoy these experiences but other foreigners shouldn't be able to come for a short time to do so as well? Of course that is a logical dead-end, and I admit this. When friends and acquaintances visit, I am delighted to show them around and try to give them valuable cultural experiences, so it's a bit hypocritical of me to be okay with that but not with a greater volume of travelers.

However, rather like someone from Sesame Street might try to push Oscar the Grouch back in his trash can so he'll stop complaining for a minute, my better nature is telling the shouty old man who lives in my heart to quit it and think rationally.

Because, despite all of these issues, I do think it is worth braving the dreaded tour buses and banana pancakers that increased global (as in, beyond Asia) tourism would bring for the many benefits it could have.

First and foremost, one of the reasons so many people around the world don't know much about Taiwan is that they've never even considered visiting. Not everyone will read the history section of their guidebook or listen to a tour guide talking about it, but enough will do so that perhaps, just perhaps, Taiwan might escape the purgatory of having the world think whatever China wants them to think about this lovely country, because they don't care enough to inquire more deeply (that's just human nature) and haven't thought to visit and see for themselves.

Secondly, I have to say Vietnam has great tourism infrastructure. Public transport within cities is lacking - and that is a problem if you want to leave the central areas of either Hanoi or Ho Chi Minh City - but no matter where you are, it is reasonably easy to arrange a ride to anything you can't walk to. For those looking to save money, they can take small group tours to, say, the mausoleums and temples outside of downtown Hue, or a group tour - some small, others not - to My Son, about an hour from Hoi An. For those willing to spend a bit more, no town is too small to not have xe om, or motorbike taxis, to take you where you need to go, and you can always arrange a car and driver (at least in the more touristy areas we visited). Hotels are not only happy to do this, they expect it. It's part of their job.

In Taiwan you might well find it impossible to see much of the scenic beauty of the country because, while you can usually get a bus to the general area of a place, to go beyond that you have to drive. There are often no taxis outside of the cities, and when there are, they are expensive to charter - not that it matters if you simply can't get one. Once in one of the smaller towns, including my perennial favorite place to get away (Lishan, in the far east of Taichung county - I refuse to call it Taichung city because it's not a city), you basically have to hike/walk/bike or depend on the kindness of locals to give you short rides. Otherwise, if you cannot or do not want to drive, you're basically screwed in much of the country. It's still one of my biggest complaints about Taiwan outside of Taipei. People defend it - oh you can just rent a scooter (not everyone can drive a scooter, nor wants to, and some foreigners have run into problems renting them without a specific scooter license) - but I'm sorry, it's really not okay and I do not accept feeble excuses. Don't even try, I'm not interested in hearing a weak-ass defense of Taiwan's crappy public transport at a local level (connections between cities are okay) outside of Taipei.

If we did start getting a larger volume of global tourists, I do think this would change. You'd have a lot of people who either couldn't or wouldn't want to drive, and suddenly people making money as hired drivers or running shuttle buses would start appearing in most places you might like to go. It wouldn't be complete, but it would be an improvement on a situation the government hasn't seen fit to improve otherwise. I'm not always a fan of the free market, but in this case it would probably fix the problem to have demand exist to facilitate the creation of supply.

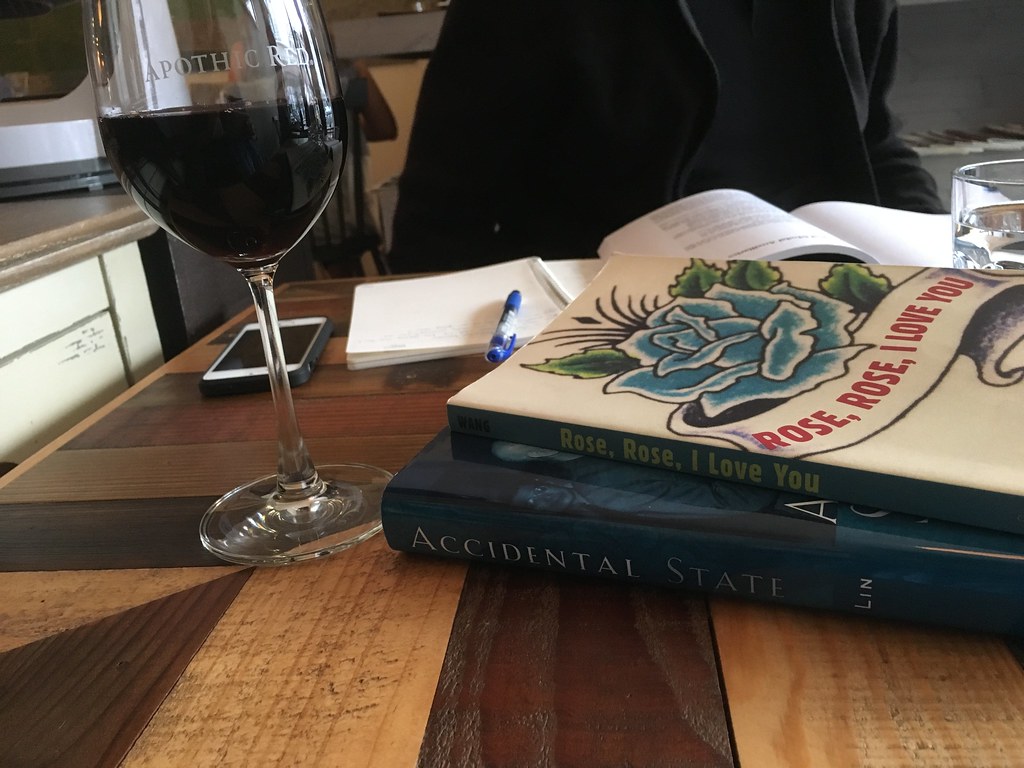

|

| I can basically see exactly this at a night market in Taiwan, but tourists are enchanted by brightly colored shaved ice street stalls in Vietnam, not here. |

I could go into the reasons why this is, but will keep it brief - in the end it comes down to China trying to erase Taiwan as a unique entity in the global consciousness, and the Taiwanese government doing a poor job of promoting tourism outside of Asia. I could write a lot more about this, but I'll save that for another post.

The central question, in fact, is this:

Part of me doesn't want this to change. I would very much like to keep Taiwan to myself. Possibly, because I am a curmudgeonly old git, I would see these backpackers I am now lamenting a dearth of, should they finally descend on Taiwan, and basically think GET OFF MY LAWN. I rather like living in an undiscovered gem of a country that isn't packed with the banana pancake set, or the wealthier set that includes their parents. I like that local culture is wonderfully uncommodified. I like that Lishan, my favorite mountain town, is a gritty little place where the most interesting things to do are read books and enjoy the view as you eat fresh fruit. All of the things that can make Taiwan annoying and inaccessible (like having to rent a car to go anywhere, and never being quite sure when temple festivals are) also make it wonderful and authentic.

It's uncharitable, but I must acknowledge that aspect of my thinking. If we did get all these tourists, we could expect every town of interest - Sanxia, Beipu, Daxi, Tainan, Lugang, Jiaoxi, Hualien, Kenting, Jiufen, Jinguashi and more - they'd all be exponentially more crowded than they already are (which is pretty damn crowded). This part is obvious, but what that means is that more businesses selling crap souvenirs - as though there aren't enough already - and other things aimed entirely at tourists will start opening, and soon enough what is now confined to a single awful lane in Jiufen will be found in every one of these towns. I do not relish that. I make no secret of my dislike for tour buses - I understand why people take them, but I always try to run ahead of the crowd of people about to be disgorged, and they do clog up the roads.

This is also uncharitable of me: what makes me so special that I get to enjoy these experiences but other foreigners shouldn't be able to come for a short time to do so as well? Of course that is a logical dead-end, and I admit this. When friends and acquaintances visit, I am delighted to show them around and try to give them valuable cultural experiences, so it's a bit hypocritical of me to be okay with that but not with a greater volume of travelers.

However, rather like someone from Sesame Street might try to push Oscar the Grouch back in his trash can so he'll stop complaining for a minute, my better nature is telling the shouty old man who lives in my heart to quit it and think rationally.

Because, despite all of these issues, I do think it is worth braving the dreaded tour buses and banana pancakers that increased global (as in, beyond Asia) tourism would bring for the many benefits it could have.

|

| We have gorgeous historic architecture too! |

Secondly, I have to say Vietnam has great tourism infrastructure. Public transport within cities is lacking - and that is a problem if you want to leave the central areas of either Hanoi or Ho Chi Minh City - but no matter where you are, it is reasonably easy to arrange a ride to anything you can't walk to. For those looking to save money, they can take small group tours to, say, the mausoleums and temples outside of downtown Hue, or a group tour - some small, others not - to My Son, about an hour from Hoi An. For those willing to spend a bit more, no town is too small to not have xe om, or motorbike taxis, to take you where you need to go, and you can always arrange a car and driver (at least in the more touristy areas we visited). Hotels are not only happy to do this, they expect it. It's part of their job.

In Taiwan you might well find it impossible to see much of the scenic beauty of the country because, while you can usually get a bus to the general area of a place, to go beyond that you have to drive. There are often no taxis outside of the cities, and when there are, they are expensive to charter - not that it matters if you simply can't get one. Once in one of the smaller towns, including my perennial favorite place to get away (Lishan, in the far east of Taichung county - I refuse to call it Taichung city because it's not a city), you basically have to hike/walk/bike or depend on the kindness of locals to give you short rides. Otherwise, if you cannot or do not want to drive, you're basically screwed in much of the country. It's still one of my biggest complaints about Taiwan outside of Taipei. People defend it - oh you can just rent a scooter (not everyone can drive a scooter, nor wants to, and some foreigners have run into problems renting them without a specific scooter license) - but I'm sorry, it's really not okay and I do not accept feeble excuses. Don't even try, I'm not interested in hearing a weak-ass defense of Taiwan's crappy public transport at a local level (connections between cities are okay) outside of Taipei.

If we did start getting a larger volume of global tourists, I do think this would change. You'd have a lot of people who either couldn't or wouldn't want to drive, and suddenly people making money as hired drivers or running shuttle buses would start appearing in most places you might like to go. It wouldn't be complete, but it would be an improvement on a situation the government hasn't seen fit to improve otherwise. I'm not always a fan of the free market, but in this case it would probably fix the problem to have demand exist to facilitate the creation of supply.

It would probably also lead to more of Taiwan's heritage architecture being restored, though I could see a good amount of it being turned into yet more souvenir shops and hotels. But refurbishing a Japanese colonial building into a boutique hotel is better than letting it moulder, no?

There are downsides of course - the poor east coast would suffer terribly, with much of the best seafront property taken up by hotels and resorts a la Sri Lanka and Vietnam. All of the above issues regarding crowding wouldn't exactly go away. More of the beautiful parts of Kenting would start to look like, well, the not-beautiful part of Kenting (Kenting town, which I avoid). More of Sun Moon Fucking Lake(tm) would start to look like the annoying part of Sun Moon Fucking Lake(tm) where hotels blot out the lake view. A lot of the best of Taiwan is, frankly, too small to accommodate that many tourists. It's not a big country and the old streets, buildings and small towns are also, well, not big. Imagine tour buses descending on Beipu. A nightmare!

I don't really want to see Taiwanese culture commodified, either. I like my all-night aboriginal festivals and do not want to watch the most popular form of engaging with indigenous culture to be one-hour dances downtown, the way Kathakali, water and shadow puppets and Kandyan dance are commodified and pruned to fit tourist tastes, for tourist consumption. I can tell you a fair amount, although I'm no expert, on pas'ta'ai. I can't tell you much at all about Kandyan dance although I packed myself into a theater to watch two hours of it with about 500 other tourists. I can only tell you slightly more about Kathakali because I attended a performance while studying in southern India. But the connection isn't there the way it is with going to the all-night real deal in the mountains. I would not want the Hsinchu pas'ta'ai to become similarly commodified and agree with a friend of mine that the way these 'cultural' or 'eco' experiences are packaged for travelers is hugely problematic.

To take another example, the one temple festival I was able to pin down a date for while my cousin was in Taiwan was in Sanxia, and was so crowded with tourists - mostly domestic, probably some Chinese - that while I wasn't able to be there, my sister reports there were so many people that you couldn't really see anything. I don't want that to be every temple parade: I like seeing one go down the street, grabbing a beer at 7-11 and then chilling out, watching it go by. Some of the most attractive parts of the countryside are already crowded enough - I don't want them to become more crowded.

On the other hand, consider Japan, where even the most rural destination usually offers some mode of transport, even if it's your hot spring hotel in the mountains picking you up from a bus station in a shuttle - and yet Japan does manage to have gorgeous countryside.

But, is it worth it to increase the international exposure of Taiwan, and get more people thinking about it as a unique place with its own unique culture and history rather than some country in Asia that they consider vaguely Chinese or confuse with Thailand? On a more secondary point, is it worth it to make the best of Taiwan more accessible to those who can't otherwise go?

Honestly - shut up Oscar - yes, I do think it is.

Not that we shouldn't do this carefully. I don't really want Taiwan to become another Thailand (as lovely as Thailand is, you have to admit, it's kind of a big-nose amusement park in some ways). I am heartened to see plenty of young, engaged Taiwanese grasping that simply swinging open the doors and offering "cultural experiences" devoid of depth to buses full of tourists is not going to be good for Taiwan. As it is now, to really appreciate and enjoy Taiwan, you have to dig. You have to do your homework. You have to know the history and cultural underpinnings to enjoy them. It's not as easy as taking a temple tour, grabbing a beer and going to the beach, the way it is in much of Southeast Asia.

I'd like to see Taiwan develop that way - if the main goal is to raise global understanding of Taiwan, then a travel experience that pushes travelers to learn more about it to appreciate it might be a good way to go (but of course would mean fewer people would come - plenty of folks do just want the easy vacation). A "you are welcome here, we have the infrastructure [please guys let's build the infrastructure, I hate having to rent cars] but we're not going to change for you" attitude, I think, is a good one to take. A "we have lots of history and historic sites, but you have to actually read the history to appreciate them" is one, too.

That may seem incompatible with attracting global tourists, but I do not think it is irreconcilable or impossible.

And now, please enjoy some photos from Vietnam.

|

| I will concede that outside of lantern festival in Taiwan, Vietnam has better lanterns. |

|

| But come on you can totally see cool tile floors and old dudes chillin' at desks in temples in Taiwan - not that most foreign tourists (outside of Asia) would know that, because they don't come. |

|

| No really, skip Nha Trang. This is better. |

|

| This is seriously the very first thing I saw in Ho Chi Minh City. |

|

| There was also a purple pigeon, and I have no idea how either of them got that way. |

|

| If you turn around and look the way Ho Chi Minh is facing, you'll see a grand boulevard full of profit-turning stores, which is kinda weird if you think about it. |