I'm sitting in my apartment in downtown Taipei as my two cats scurry around the living room and my husband cleans up from dinner. I think about my job, my friends, my pets, my home which I am very comfortable in, my life and my livelihood, and they are all in Taiwan. I think about what I would lose if I were to leave, and it's quite a lot. I have no home in the US and no obvious city to move to there. My prosperity is tied to Taiwan's prosperity. Taiwan is my home, and it would affect my life profoundly if I were to leave.

However, this is not reflected in my legal status (I've written about why before).

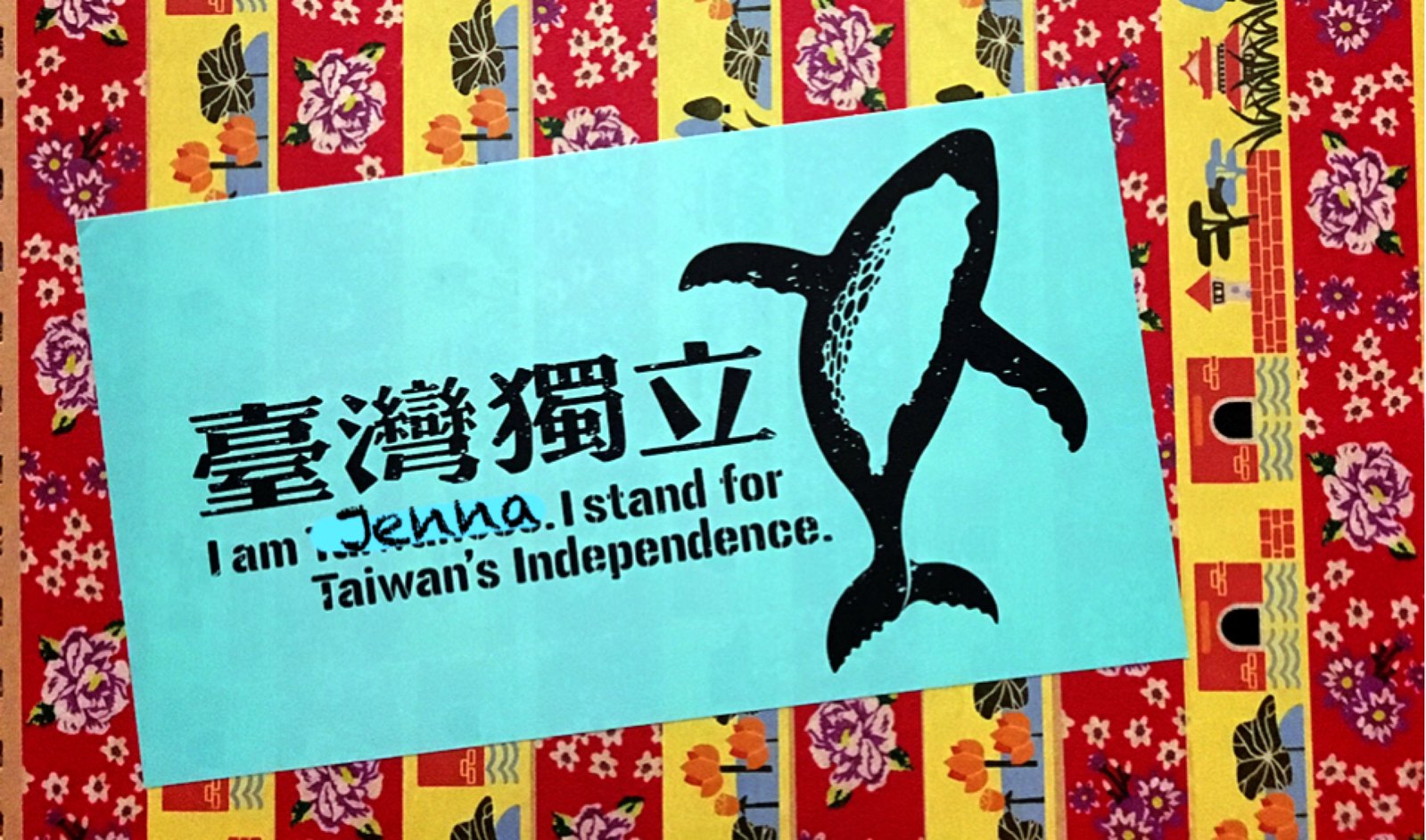

This is not a post about dual nationality, though, it's a post about the battle for Taiwan's soul, and what it means when we are too kind to those whose ultimate goal is to bring Taiwan as close to China as possible even when public sentiment is not in their favor - and what happens when we downplay their side of the argument while telling those with legitimate points of contention to settle down and play nice.

This is, however, related to my own struggle.

The laws that keep me foreign are Republic of China laws, written in China before the ROC had any reason to claim, or desire to claim, Taiwan.

Contrast that with the welcome Taiwan gives me: a lot of foreign residents here say they are singled out, treated as 'other', not allowed to assimilate. Sometimes that happens to me too, but most of the time I live my life and am treated like a normal person and normal neighbor. Most people I talk to have no idea that I can't become a citizen without giving up my American citizenship and are horrified to learn that fact.

I can't help but feel that while Taiwan wants me here, the ROC doesn't.

There have been attempts to patch up these differences through amending the laws but none have been sufficient. This issue is a microcosm of a bigger problem: the legal system of the Republic of China and the framework Taiwan actually needs to build the country most want it to become are irreconcilable. There is no patch that can fix it - the framework can't just be amended. It needs to be completely revamped.

So, when people say "the ROC is just a name", or "let's not fight over nomenclature and symbols", I do get annoyed. My life is directly impacted by the existence of the Republic of China, and it goes well beyond a name, right down to laws that were written in Nanjing in the 1920s without any reason to consider Taiwan or what kind of country it might become.

Considering all of this, I just can't agree that the symbolism of Double Ten day is mere imagery. It may be true that in the great swaths of the non-political, colorless or centrist population that we are more alike than we are different, but what differences we have run far deeper than a flag, an anthem and a name.

I also cannot agree that it is mere imagery that divides us. There is a portion of the population in this country who may not be pro-unification, but who do think of Taiwan as ultimately Chinese. This is not a minor difference that can be ignored: it informs all sorts of beliefs.

In fact, I genuinely do not believe this is true:

The fact of the matter is, and notwithstanding the nomenclatural issues that arise for many within the green camp, today’s ROC — how it is lived and experienced on a daily basis — is a transitory, albeit official, byword for what everybody knows is Taiwan.

No, not really. Today's ROC for many - not for everyone, I concede - is a byword only for "the ROC", which is in Taiwan and includes Taiwan, but is Chinese. It's a byword for the ultimate cultural underpinnings of Taiwan, and for something they quite likely hope will happen someday: a liberalized and democratized China that they can convince the Taiwanese to happily unite with. Perhaps not in their lifetime, but someday. This is what they mean when they say they are not pro-unification.

It is a byword for "let's not rock the boat" at best, for "no matter what you say you are fundamentally Chinese" or "no matter what people think being Taiwanese is about having Chinese ancestry" at worst.

Wait, no, at worst it is a byword for - and this is a real quote from Foxconn chairman Terry Gou - "you can't eat democracy".

If I am wrong and "the ROC" is, in fact, a byword for "Taiwan", somebody better tell my neighbors, because they sure don't see it that way.

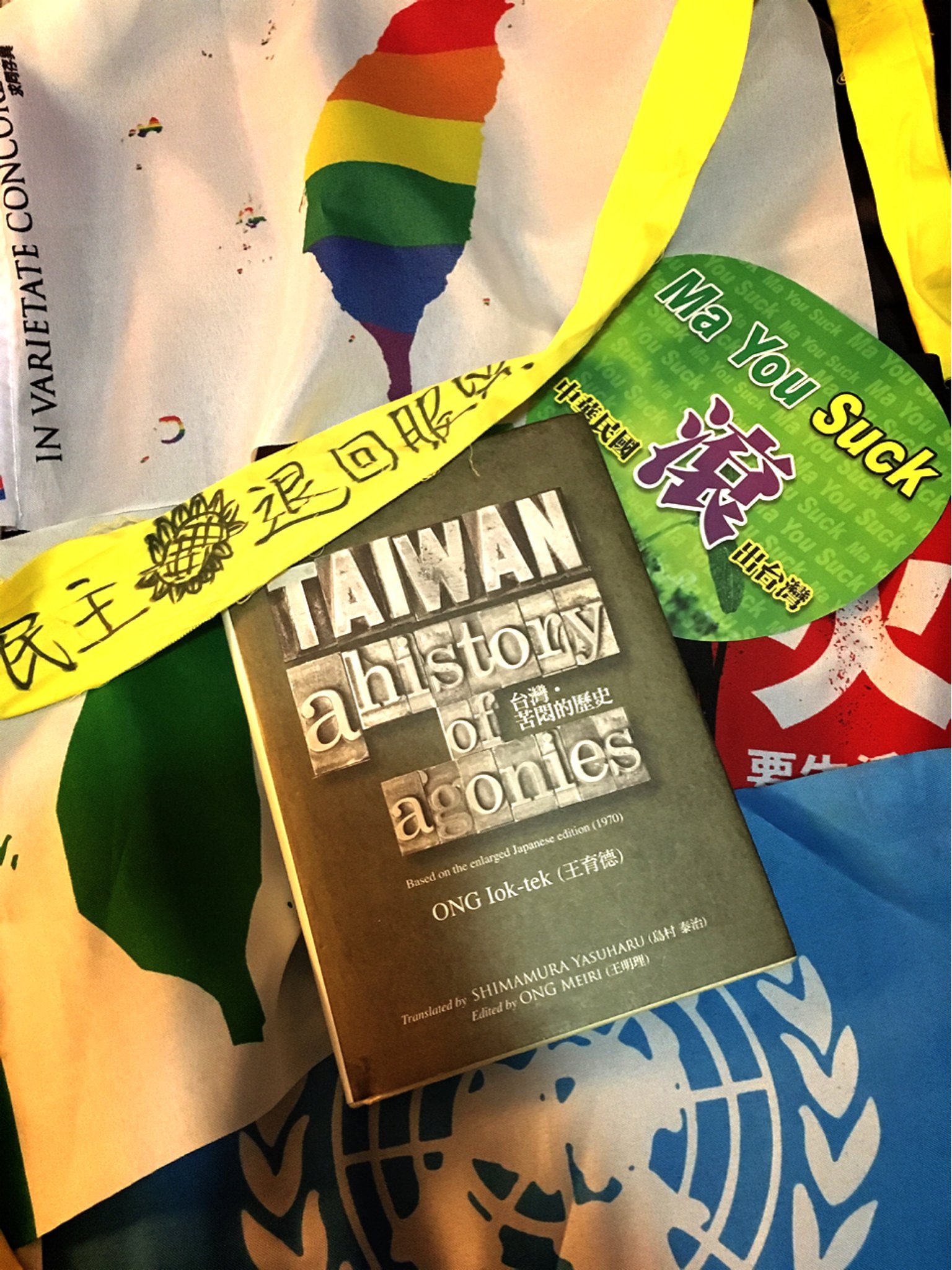

It is the driving belief behind rewriting history to make the KMT seem benevolent - "228 was a necessary step to 'stabilize' the situation in Taiwan" - and those who fought for Taiwanese democracy "troublemakers" (while re-writing that democracy as some kindly deathbed wish by an enlightened and saintly Chiang Ching-kuo). It's the belief marginalizes all non-Mainlanders, which prioritizes Mandarin as the primary language and Chinese history and culture as the primary focus in schools. It's the belief which keeps pushing for economically problematic deals with China. It's the driving force behind treating Taiwanese culture and language as something for 'peasants' and teaching children that before the KMT came in and "fixed everything", Taiwan was a poor backwater (this is, of course, completely false). It is the side that complains about Taiwanese who won't call themselves "Chinese", as though anyone had any right to tell someone else how to identify.

It is a byword for all of these things - for how they want Taiwan to be, in direct contradiction to public sentiment as well as what Taiwan already is.

One can argue that those who hold these beliefs and yet do want to see a future for Taiwan are just another side of the pro-independence coin, and I'd actually agree to an extent. I'm not that interested in the "taidu" vs. "huadu" debate; I find the whole thing a bit overcooked. Those who want Taiwanese independence can want it however they want, and I too am not sure there's a huge difference.

What I am interested in, however, is the papering over of the pro-China slant of the KMT. For example (and from the same link above):

Thus, despite its [the KMT's] stronger identification with ROC symbols and nomenclature, it is unfair to describe today’s mainstream (read: electable) KMT as pro-unification; when one recent chairperson flirted with the idea of uncomfortably closer ties with China she was quickly cast out and will be no more than a footnote in the party’s history.

That isn’t to say that a number of KMT politicians have not, rather unhelpfully, played the China card in a bid to gain an electoral advantage against their opponents from the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) or the New Power Party. But more often than not this was political expediency rather than the expression of an actual commitment to PRC ideology or unification.

Here's the problem with that: just as being pro-independence no longer means voting for a pan-Green party, being pro-China no longer means being pro-immediate-unification. Being against immediate unification does not mean one is against eventual unification.

The politicians who use "closer ties with China" as a campaign platform aren't doing so for political expediency alone: they may not support unification now, but generally do not believe in independence, ever. This is not "huadu". This is a "let's wait it out" pro-China belief system.

Generally speaking, it is pretty clear to me that their deeper political beliefs are oriented towards China: a cultural and ethnic (Han) notion of China that transcends PRC and ROC, but ultimately ends with unification, because Taiwan is simply not a wholly separate identity to them, and will never be. Not in this generation, anyway. They are not "huadu", they are "status quo right now, unification someday far down the line". There is no "du" (independence) about their beliefs, only biding time.

Those who have no love for an PRC ideology do not necessarily believe that Taiwan's future is one that is free of China. Remember, they feel Taiwan is ultimately Chinese and they are offended and threatened by the idea of a separate Taiwanese identity that has no ties to China beyond a few dubious ethnic links and a few hundred years of being a colony of the Qing. Being pro-China, rather like being pro-Taiwan, is also on a spectrum. They are not necessarily on our side for the long haul.

You don't have to be a unificationist to feel that way. You don't have to be White Wolf or Hung Hsiu-chu. You can be any run-of-the-mill politician who still stands by the old symbols of a dead regime, who still feels Taiwan is Chinese.

And, if you still feel Taiwan is Chinese, you can use that to justify not teaching much Taiwanese history in schools, whitewashing what history you do teach, and continuing to be dismissive of expressions of Taiwanese identity and the cultural importance of the Taiwanese language (you might even, against all linguistic evidence, insist that it is merely a "dialect").

It is about way more than the imagery: it's about the ultimate identity of Taiwan, and about how that identity informs everything from a constitution that no longer adequately governs the Taiwan we have today, to a legal and governmental framework that does not fit Taiwan - remember, we got rid of the Tibetan affairs council very recently and we still don't treat China like a regular foreign country. It also includes everything from fundamental ideas of how children should be educated - what history they should be taught and why - and which languages should be given priority to what extent Taiwan should move away from being a state whose citizenship rests mostly on family history to one that is more international.

It is not just nomenclature, and it is not just an anthem. It is more than imagery. It directly impacts lives, including mine.

The politicians who use "closer ties with China" as a campaign platform aren't doing so for political expediency alone: they may not support unification now, but generally do not believe in independence, ever. This is not "huadu". This is a "let's wait it out" pro-China belief system.

Generally speaking, it is pretty clear to me that their deeper political beliefs are oriented towards China: a cultural and ethnic (Han) notion of China that transcends PRC and ROC, but ultimately ends with unification, because Taiwan is simply not a wholly separate identity to them, and will never be. Not in this generation, anyway. They are not "huadu", they are "status quo right now, unification someday far down the line". There is no "du" (independence) about their beliefs, only biding time.

Those who have no love for an PRC ideology do not necessarily believe that Taiwan's future is one that is free of China. Remember, they feel Taiwan is ultimately Chinese and they are offended and threatened by the idea of a separate Taiwanese identity that has no ties to China beyond a few dubious ethnic links and a few hundred years of being a colony of the Qing. Being pro-China, rather like being pro-Taiwan, is also on a spectrum. They are not necessarily on our side for the long haul.

You don't have to be a unificationist to feel that way. You don't have to be White Wolf or Hung Hsiu-chu. You can be any run-of-the-mill politician who still stands by the old symbols of a dead regime, who still feels Taiwan is Chinese.

And, if you still feel Taiwan is Chinese, you can use that to justify not teaching much Taiwanese history in schools, whitewashing what history you do teach, and continuing to be dismissive of expressions of Taiwanese identity and the cultural importance of the Taiwanese language (you might even, against all linguistic evidence, insist that it is merely a "dialect").

It is about way more than the imagery: it's about the ultimate identity of Taiwan, and about how that identity informs everything from a constitution that no longer adequately governs the Taiwan we have today, to a legal and governmental framework that does not fit Taiwan - remember, we got rid of the Tibetan affairs council very recently and we still don't treat China like a regular foreign country. It also includes everything from fundamental ideas of how children should be educated - what history they should be taught and why - and which languages should be given priority to what extent Taiwan should move away from being a state whose citizenship rests mostly on family history to one that is more international.

It is not just nomenclature, and it is not just an anthem. It is more than imagery. It directly impacts lives, including mine.

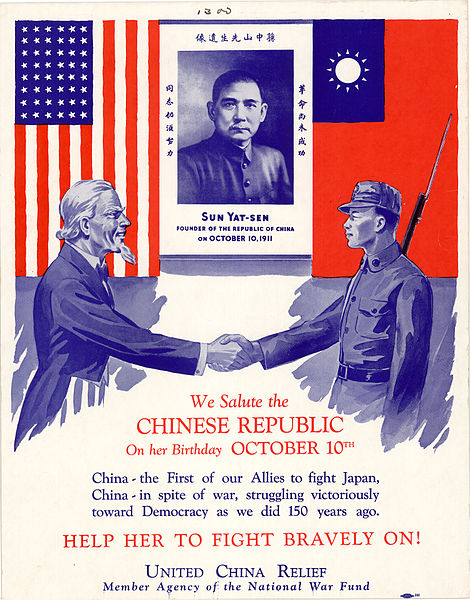

That said, let's take a look at that imagery. I don't think enough people appreciate that the reason why the pro-Taiwan side hates the flag of the Republic of China is not necessarily because it is not a flag that originated in Taiwan. Certainly that is an issue, but what inspires such disgust for the ROC flag is that big ugly KMT sun. The reason people protest the national anthem is not that it's "not Taiwan's anthem". That surely instills some level of dislike or annoyance in many, but a lot of it is the lyrics that blatantly refer to one party (just look at the first few lines). The issue is not as much the ROC as it is the KMT's centrality and privilege within it. Many see that flag or hear that anthem and think of the relatives and ancestors that that party killed, imprisoned, tortured or "disappeared" - and yet there they are, still on the flag, still in the anthem.

How is it not obvious why this bothers them? Why should they be the ones to bridge this gap and accept symbols that are directly linked to the pain of their history?

Why should people be expected to "set aside" this difference? Why on earth should they have to pretend it's not a problem?

Yes, we have an ROC in which the KMT is out of power, but they still occupy that place of privilege on the flag and in the anthem. I do not see how it is acceptable that one party is enshrined in this way in a democracy, and do not see how such symbols can ever be viable symbols for that democracy.

Why should they look at that flag, celebrate Double Ten or hear that anthem (or look at that portrait of Sun Yat-Sen) and think Taiwan? If I were Taiwanese, I wouldn't.

I can't condone an attitude that the victims of a historical injustice should just quiet down already, because they're causing trouble with their protesting that the party that once killed their family members and mucked up their country for a generation still has their damn sun on the flag like it's all okay.

Yes, in today's Taiwan it is possible to refuse to sing the first two lines of the anthem, or to change the lyrics. It is acceptable to refuse to pay homage to Dr. Sun. It is okay to speak your mind about the flag and the party logo enshrined on it.

The problem is, we shouldn't have to do any of that. Taiwan deserves a flag that doesn't remind some of its citizens of the suffering of their ancestors, an anthem we can stand for proudly and a holiday that doesn't give us mixed feelings.

It doesn't do anyone any good at all to say we should push all of that down and pretend it's not a problem. It very much is.