I took this photo years ago and it seemed appropriate to finally use it here.

I had thought I'd written about this before, but couldn't find an appropriate post. So, because it seems like I address this opinion frequently and I'm sick of repeating myself, it's time to write it all out here so I can link it next time someone comes out with a wacky historical interpretation of what actually happened after the Chinese Civil War.

Also, Dictatorship Day is tomorrow (that's 10/10 for those of you who are still sleeping), so this feels like a good time to write such a post.

So, what am I on about? Every few weeks, either wild-caught or while I'm talking about one of my favorite subjects (what an absolute sack of wankers the KMT is), someone seems to pop into one of my feeds with a comment along the lines of "yes but without Chiang Kai-shek/the KMT/the ROC army Taiwan would be a part of Communist China now".

These include comments by good people -- it's not personal. I've been wrong about history too. It's okay. But we need to deal with it.

This needs to be tackled in a few parts, in fact. First, I think it's important to clarify what exactly the KMT and CCP each thought of Taiwan in the years leading up to the Taiwan conflict. Only then do I think we'll have a good basis for discussing the degree to which Chiang and the KMT are not responsible for keeping Taiwan CCP free.

So first, let me make the case that Chiang Kai-shek is to blame for the CCP's interest in Taiwan in the first place.

You read that right. It's all his (and the KMT's) fault that this is a problem to begin with.

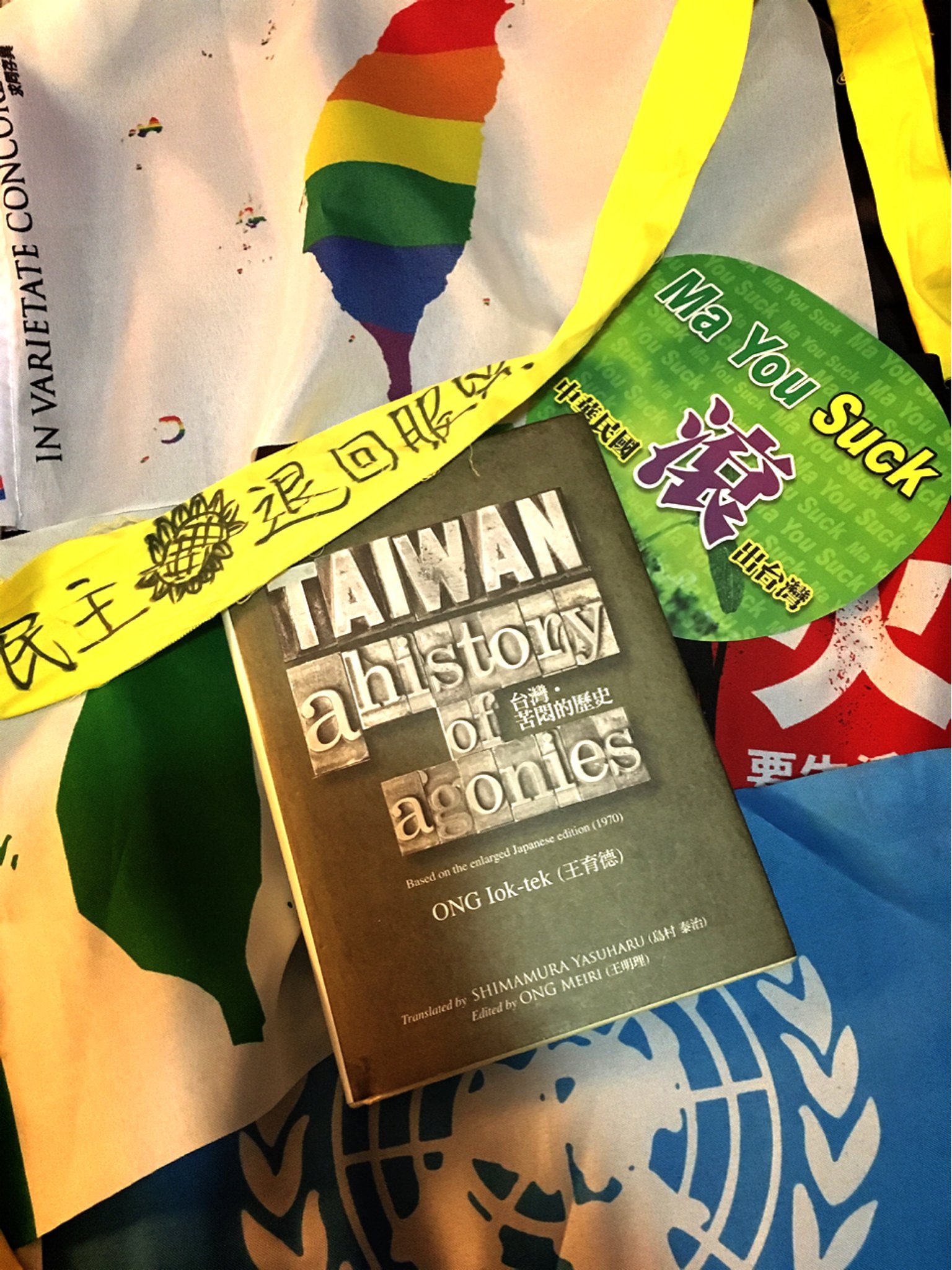

I don't have many links for you because my biggest source is one of my favorite books, Accidental State by Hsiao-ting Lin, but I will link where I can.

In 1924, Sun Yat-sen did include Taiwan in his Three Principles of the People, and it's likely Chiang got the idea to include Taiwan in the territories claimed by the Nationalists at the summit in Cairo in 1943 from this, according to Lin. Here's the thing though: Sun also included all sorts of places that no reasonable person believes "China" should control, including parts of Korea, Burma, Vietnam, Nepal, Bhutan etc. It also is not clear from Sun's other writing that when visiting Taiwan (he visited twice, I believe) he considered it to be anything other than Japanese territory.

What does matter is this: it was not clear until right before the meeting at Cairo that Taiwan would be included in Nationalist territorial claims the way, say, Manchuria certainly would be, as Taiwan had been ceded legally under the Treaty of Shimonoseki whereas the Nationalists had never accepted Japan's conquest of Manchuria. Before that, the ROC, its officials and Chiang himself had more or less treated Taiwan as a part of Japan, including opening a consular office in Taipei "under the jurisdiction of its legation in Tokyo". Chiang even spoke to Japanese politicians about how ending colonial rule in Taiwan and Korea could help bolster relations between China and Japan! To say the least, before 1941, Nationalist views of Taiwan and clear ideas about what Taiwan should be were, to use Lin's words, "murky", "cautious", uncertain" and "undetermined".

The change in rhetoric to seriously consider claiming Taiwan happened after Pearl Harbor, when the ROC more or less saw an opportunity and decided to grab it. It was around that time that a definition of what constituted "lost" territories to be recovered was created by Chiang, and the top concerns regarding what should be included and what shouldn't were more geo-strategic than ideological.

In fact, according to Lin, the decision to include Taiwan as a claimed territory wasn't even finalized until after Chiang had received the invitation to Cairo! Until then it had been a matter of debate and exactly which "lost" territories ought to be "recovered" was very much a matter of debate.

George Kerr also notes in Formosa Betrayed that Allied attempts to gain intelligence on Taiwan from their Chinese allies showed how little interest the Nationalists actually had in Taiwan, as most of it was lazily thrown together at best, or outright fabricated at worst (to be fair, Lin finds Kerr's accounts to be generally exaggerated).

The inclusion of Taiwan didn't start gaining truly serious ROC domestic or international traction until the Allies signed onto it at Cairo, and even then, to quote Kerr, the only reason the West was willing to prop up Chiang's claims was to help him save face as the self-proclaimed greatest leader and bringer of "democracy" to Asia (again, to be fair, no-one else in Asia at that time could reasonably claim the title of supreme democratic reformer, either). They knew perfectly well that his regime would require massive support from the West.

(It's worth taking a brief side-note here to point out that the result of Cairo was a declaration, not a treaty. The actual series of treaties that followed the Japanese surrender do not clarify to whom Taiwan was ceded nor what its status is.)

At the same time, the Communists seemed to hold a very different view of Taiwan. Mao's rhetoric on the topic somewhat implied that Taiwan had the right to some, if not total, sovereignty, and the CCP listed "Taiwanese" among the "minority nationalities" that had "equal rights" in "Soviet China", but were considered to be a distinct group or race from Chinese with their own homeland.

I'm going to quote from the link above at length, because unlike Accidental State and Formosa Betrayed, two books you absolutely should spend your money on, this is a journal article and not everyone will have access. I've emphasized important points:

This position of the Sixth Congress was reiterated in the same year by the Fifth National Congress of the Chinese Communist Youth League, which in its regulations noted that the "minority na- tionalities" in China included "Mongols, Koreans, Taiwanese, Annamese, etc.," and urged that local organs form national minority committes.5 Two years later in Kiangsi, the "Draft Constitution of the China Soviet Republic," adopted by the First All-China Soviet Congress (November 7, 1931), extended constitutional rights to these same minority nationalities.6 According to Item 4 of this document, all races, that is the "Han, Manchu, Mongol, Mohammedan, Tibetan, Miao, Li and also the Taiwanese, Koreans, and Annamese who reside in China, are equal under the laws of Soviet China [emphasis added]." Taiwanese were seen not as Han but as a different "nationality" and even "race," who like the Koreans and the Annamese, but unlike the other minorities, came from a homeland separate from China.8 This view is strengthened by the fact that the CCP never referred to the Taiwanese as "brethren" (dixiong), or "the offspring of the Yellow Emperor," or "compatriots" (tongbao), who would de facto belong to the Han after they return to China. Indeed, a 1928 Central Committee Notice, while calling for the recovery from Japan of sovereignty over Shantung and Manchuria, failed to mention a similar goal for Taiwan in its seventeen "general goals of the present mass movement."9 Since the ideological perspectives of the early Chinese Communist elite were heavily influenced by an anti-Japanese (as well as an anti-Western) nationalism born out of the May Fourth Movement, this exclusion of Taiwan from recoverable sovereign territory of China is revealing.

(Yes, that is one long paragraph.)

It gets better, though:

Mao Tse-tung's earliest comments on the Taiwanese came in his January 1934 "Report of the China Soviet Republic Central Executive Committee and the People's Committee to the Second All-China Soviet Congress." Commenting on various provisions in the 1931 Constitution, he said: Item 15 of the Draft Constitution of Soviet China has the following statement:

To every nationality in China who is persecuted because of revolutionary acts and to the revolutionary warriors of the whole world, the Chinese Soviet Government grants the right of their being protected in Soviet areas, and assists them in renewing their struggle until a total victory of the revolutionary movement for their nationality and nation has been achieved. In the Soviet areas, many revolutionary comrades from Korea, Taiwan, and Annam are residing. In the First All-China Soviet Congress, representatives of Korea had attended. In the present Congress, there are a few representatives from Korea, Taiwan, and Annam. This proves that this Declaration of the Soviet is a correct one.’

Mao not only reaffirmed the Chinese Communist position that Taiwanese residing outside Taiwan and in China were a "minority nationality," but also implied CCP recognition and support of an independent Taiwan national liberation movement, which would be united in a joint effort with the Chinese movement, but with a different purpose, i.e., the establishment of an independent state similar to other Japanese colonies, such as Korea.

A year later, Mao and P'eng Teh-huai manifestly dissociated Taiwan's political movement from China by incorporating it into the anti-imperialist revolution led by the Japanese Communist Party. According to the "Resolution on the Current Political Situation and the Party's Responsibility," passed at a meeting of the CCP Central Political Bureau on 25 December, 1935, and signed by P'eng and Mao:

Under the powerful leadership of the Japanese Communist Party, the Japanese workers and peasants and the oppressed nationalities (Korea, Taiwan) are preparing great efforts in struggling to defeat Japanese Imperialism and to establish a Soviet Japan. This is to unite the Chinese revolution and Japanese revolution on the basis of the common targets of "defeating Japanese imperialism." The Japanese revolutionary people are a powerful helper of the Chinese revolutionary people."

Here Taiwanese were not considered an integral part of the "Chinese revolutionary people," but were treated as a people whose natural political role was to fight alongside the "Japanese workers and peasants" in establishing a Soviet Japan. Whether Mao and P'eng expected the Taiwanese (and Koreans) formally to join a newly-created Soviet Japan is unclear from this resolution. But nowhere in this or other documents examined by the authors did CCP leaders suggest that the Taiwanese should fight to return to their "motherland" and join Soviet China - a point they would not make until after 1943.

That's my underline, so let me reiterate:

...a point they would not make until after 1943.

What changed between when these statements were made and 1943?

Oh yeah! All that stuff the Nationalists did, under the leadership of Chiang Kai-shek, to change China's perspective on Taiwan toward claiming it as an integral territory and 'lost' province.

It is not unreasonable to assert that the CCP changed its stance on Taiwan because the Nationalists had done so first.

Guess what - it gets even better. Please enjoy:

As to explicit CCP support for an independent state on Taiwan, the most notable documentary evidence is Mao's personal statement made to Edgar Snow on July 16, 1936. Responding to Snow's question, "Is it the immediate task of the Chinese people to regain all the territories lost to Japanese imperialism, or only to drive Japan from North China, and all Chinese territory above the Great Wall?," Mao answered:

It is the immediate task of China to regain all our lost territories, not merely to defend our sovereignty below the Great Wall. This means that Manchuria must be regained. We do not, however, include Korea, formerly a Chinese colony, but when we have re-established the independence of the lost territories of China, and if the Koreans wish to break away from the chains of Japanese imperialism, we will extend them our enthusiastic help in their struggle for independence. The same thing applies for Formosa. As for Inner Mongolia, which is populated by both Chinese and Mongolians, we will struggle to drive Japan from there and help Inner Mongolia to establish an autonomous State.

The support for independence of Korea and Taiwan, both of which were formerly linked to China, is clearly stated.

There is some solid analysis in this otherwise older source about why the CCP policy was able to shift, and an interesting discussion of what constitutes "Chineseness" in the eyes of the CCP -- at least, the best possible analysis of it in 1979.

The authors also go on to provide more source material for Lin's analysis of the shifting Nationalist position on Taiwan pre-1943, pointing out that Taiwan was of minor importance before Cairo, belying the massive importance placed on it by the Nationalists after the conference. They go on to posit that Chiang's original goal was quite possibly very similar to the CCP's: to "liberate" Korea and Taiwan so as to create buffer states between China and Japan!

Because I believe in free access to academic work, here's another quote:

What is important here is that Chiang, like Sun, was more concerned with "restoring" (hufifu) the independence and freedom of Taiwan and Korea so as to create buffer states against Japan, while China would assume traditional protection, but not necessarily sovereignty, over Taiwan and Korea. Moreover, throughout Chiang's pre-1942 collected works and speeches nowhere does he make a claim to “recover" (shoufu, guangfu or shouhut) Taiwan. The island was mentioned occasionally, along with Korea, but only in the sense that both nations were enslaved by the Japanese. No mention of the Taiwanese appeared in such strong nationalist tracts as "Prepare For Victory," nor in his message on "Resistance in the Enemy's Rear."

Although the ability of the CCP to shift so easily to a "Taiwan is an inseparable part of China" stance is of interest, the reason why they chose to do so at all is of more interest to me. Again, it all points back to Cairo, and we have Chiang Kai-shek and his minions to thank for that.

Hsiao and Sullivan (the heroes of this heavily-quoted article) reached the same (hedged) conclusion in 1979:

This tentatively suggests that the Chinese Communist position on the Taiwan question became most politically expedient after the 1943 Cairo Declaration when, still out of power, and in a subordinate position vis-a-vis the KMT, the CCP dropped its support for Taiwan's independent status and embraced Chiang Kai-shek's then very recent policy of full political reintegration of Taiwan into the Chinese polity.

!!!

I emphasized that in three different ways to draw your attention to it. It's analysis, not fact, but I happen to think it's right on the money.

In other words, Chiang didn't "save" Taiwan from the Communists. He led them right into claiming Taiwan as a territory. If Chiang and the Nationalists had never fed that fire, it's entirely possible (though far from assured, to be fair yet again) that the CCP would have never become as interested in Taiwan as an integral part of China as they did. They might have had designs on it, after all they got involved in conflicts in Korea and Vietnam, but note that Korea and Vietnam don't suffer from the lack of diplomatic recognition or the same territorial claims by China (or at least, in Vietnam's case, not to the same extent) that Taiwan does.

And yet, there are still people who believe that Chiang deserves some sort of credit for keeping the Communists away from Taiwan. I would ask -- why? He's responsible for their claims on Taiwan in the first place!

At this point we veer into speculative history: if the Nationalists had never decided to claim Taiwan, would they have occupied Taiwan at the behest of the Allies in 1945, for convenience's sake? I don't know, as occupying Taiwan as a proxy of the Allies is not the same as occupying it as a claimed territory, but it seems at least somewhat less likely. In any case, it is less likely to have become the location of their retreat upon losing the civil war a few years later. This means that perhaps (?) the Nationalists might have been wiped out completely -- not a bad outcome, in my estimation, though the CCP disappearing would be even better.

If the KMT had not retreated to Taiwan, would the CCP have ever set its sights on the island? Possibly. There would have been so-called "justification" for it in Sun's writing, and they certainly were (and are) expansionist.

But their own writings indicate that it might not have rolled out that way, and Taiwan would have gained its independence in the same era as many other former colonies across Asia: Korea, most of Southeast Asia, India and more.

Some of those former colonies have struggled (the Philippines, Myanmar, India, Indonesia), in part due to local issues and in part thanks to everything that was stolen from them or forced upon them by their colonizers. Others (Korea, Singapore) eventually succeeded -- if we take democracy and freedom as important markers of success, Korea even more than Singapore. As a relatively prosperous colony under the Japanese with much of its infrastructure already built (and built well), how might Taiwan have fared? We'll never know, but it's not a given that it would have been worse than under KMT rule.

Importantly, if this is how it had played out, there might not have been any question now of whether Taiwan was a 'part of China', any more than that question is being asked of those other countries. All the missiles, all the threats, all the fighter jets -- none of it would be dangled over our heads by an angry CCP.

All because they slobbered after the Nationalists and that led their sights right to Taiwan.

Blame the CCP, yes, but also...blame the KMT. They literally created this mess. They literally wrote the paper on how to screw Taiwan.